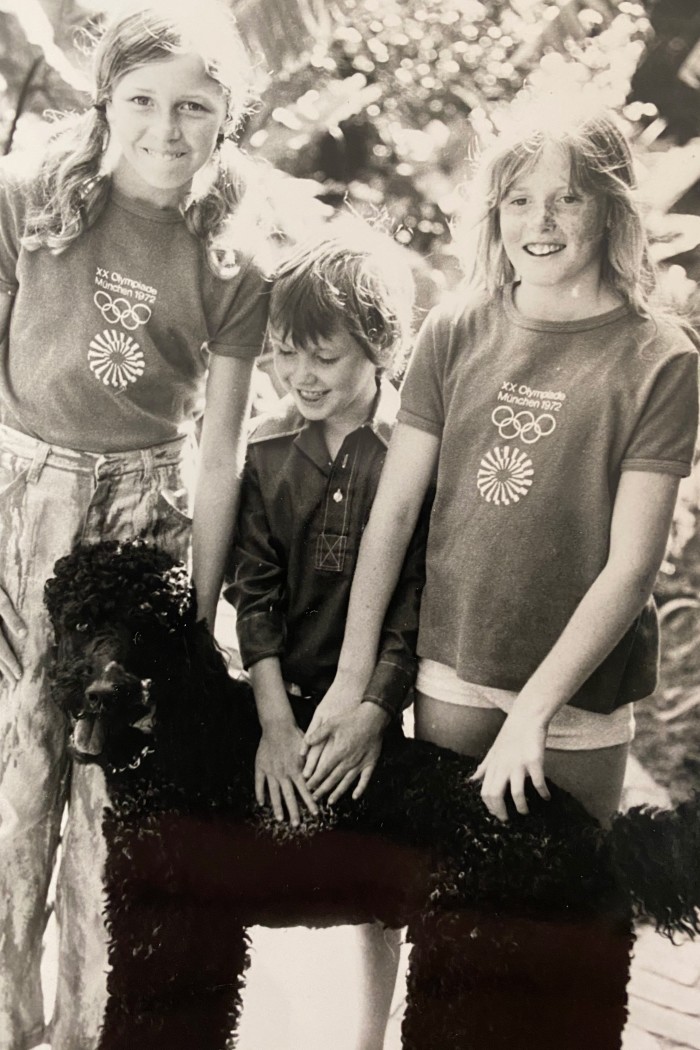

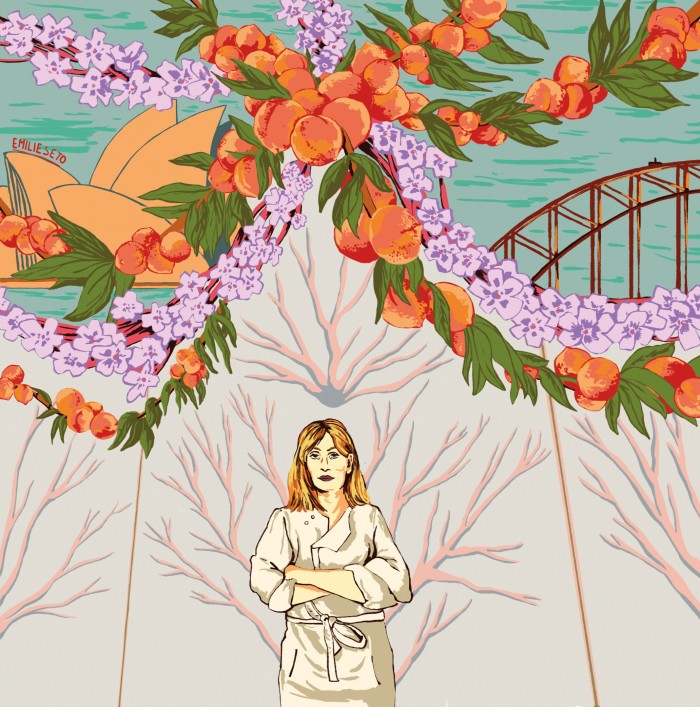

How I Spend It: Skye Gyngell on her childhood in Australia

Simply sign up to the Style myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

One of the reasons I became a chef was because of how our senses of smell and taste capture memories so well. When I create dishes at my restaurant Spring in London I’m always thinking of that; verbena and peach takes me back to a hot summer childhood in Australia, for example. My cooking is a way of trying to reproduce happy moments.

I left Australia quite early – at 19, to attend cookery school in Paris – and I’ve never really lived there again, so now much more than half my life has been away from the country of my birth. For a really long time it felt so strange that I couldn’t find anyone who shared common childhood ground with me. There was no one who could understand the excitement of lying in bed under a tin roof, and the noise of the rain drumming down so loudly that you couldn’t hear anything else. I didn’t talk about it because I didn’t know how to describe what it had been like as a child – I felt disconnected.

Later, I’d go home to Australia and my sister would laugh at me because I would spend a day just driving around old haunts, such as Nielsen Park in Sydney. She couldn’t understand why I needed to take these trips down memory lane, but I felt I just had to remember they were there. It was some sort of comfort. I wonder whether that’s the reason why I started to gather things, to have them around as a point of reference for me. Because I couldn’t turn around and say to someone, “Remember that time when we ran down that hill at Bondi?” There was no one who knew. There was a rootlessness.

Over the years, my house in London has become a kind of nest, a place to accumulate my memories and experiences. It feels very un-English and quite Australian. My mum was really sweet and gave us a lot of furniture from our childhood when she sold her house. I’ve also got paintings, like one from a great Australian artist called Justin O’Brien. Then there are these amazing little painted tin dogs made by an aboriginal community. I always bring things home from Sydney – big jars of Vegemite, Dr Paw Paw cream, the brands that feel important to you because you grew up with them, or on them, in the case of Vegemite. And there’s a shop in Sydney called Chee Soon & Fitzgerald, which does amazing things with Japanese fabrics and Australian prints. I buy all my tea towels from there.

I try and get home as much as I can because, apart from my children, my family are all there. I last went to Sydney for a month in December 2019 and was there during the bush fires, which were so devastating. You could smell it in the air, the sun was the most peculiar colour. And yet I had this really funny feeling that it was so important for me to be there while it was happening. I couldn’t figure out whether that was a macabre feeling. Was I being a voyeur? But I think if you grow up in Australia, the flora and fauna are in your DNA – you live your childhood outside in this landscape that is so huge you feel you could almost fall into the sky. I was happy to be home but also so sad. You couldn’t deny that there was a climate crisis. It’s thought that something like three billion animals were wiped out or displaced in those fires. And then three weeks later the pandemic came.

Time has passed and I’ve made my family, their childhoods were spent here in London, and we made new memories. I’ve become one of those people who’s not really Australian, not really English, neither one thing nor the other. But recently I have spoken to other Australians in London and, like them, I feel a huge yearning to go back home. I need sun on my face and salt water on my body – that’s all I can really think about. I feel so mixed up about it because I think that environmentally we shouldn’t really travel the way we had been travelling – and yet the only thing I want to do is get on a plane home.

In Australia, home is not a house to me any more because my family home is long gone, and my brothers and sisters have their own lives and kids. But that landscape is definitely home. When we were little kids, if anything went wrong, if you had a cold, a cut, you were told, “Get in the sea, you’ll feel better.” It was the great healer. I just want to put my head under salt water.

Comments