My Favourite Pieces: Contemporary crafts with the power to surprise

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Helen Drutt’s approach to collecting jewellery is very specific. “I look for something that takes me where I have never been before,” the former gallerist says. It is a feeling she experienced when she bought her first contemporary piece, a 1966 electroformed brooch by the US jewellery artist Stanley Lechtzin.

“I screamed,” says Drutt, who previously had not ventured much beyond pearls or a circle pin brooch. “I had never seen anything like this.”

Her interest in contemporary crafts was piqued by what she saw as a resurgence in the US after the second world war, and she started visiting woodworking, weaving and ceramics studios. Now 90, she co-founded the Philadelphia Council of Professional Craftsmen in 1967, and ran her eponymous crafts gallery in the city between 1973 and 2002.

Drutt used jewellery as a catalyst for discussions about the wider field. “I couldn’t come into a meeting at the museum or at an architectural conference carrying a chair; I couldn’t carry a pot,” she says. “I had to have something that ignited their interest in the crafts, and I wore jewellery because it was small.”

The Goldsmiths’ Company in London — a membership organisation that supports craftspeople — made Drutt an associate earlier this year in recognition of her international advocacy for jewellers. As a consultant to museums, an author and a collector, she continues to champion makers: she wrote the preface to a book for the current Goldsmiths’ Centre exhibition, The Brooch Unpinned.

Merrily Tompkins brooch (2008)

Drutt’s late friend Tompkins pinned this “very funny” brooch on her at an exhibition opening. Made from copper, brass, silver and found objects, the gift is a portrait of Drutt. It features her trademark hat, the Breon O’Casey bracelets she never leaves the house without, a magnet representing her collecting of fridge magnets, a Michael Lax teapot to remind her how Tompkins would buy replacements when Drutt burnt hers on the stove, and a mobile phone because the pair called each other at unpredictable moments.

A letter represents their correspondence. “When I was 75 years old, she sent me a card with 75 lipstick impressions and she wrote a note that said she ran out of lipstick and really was upset,” says Drutt. “I have it framed in my house; it’s really wonderful.”

Pulling the circle pin at the bottom — a nod to her taste before she saw the Lechtzin brooch — moves the hands up and down. Drutt plans to gift the piece to a museum. She has already given away parts of her collection, including 800 pieces of jewellery and drawings to the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.

Gerd Rothmann thumbprint necklace (2019)

Another surprise present, Drutt’s silver necklace features 137 thumbprints of her husband Peter Stern, who died in 2018 and was co-founder of the Storm King Art Center sculpture park in New York state. The German jeweller made a mould of Stern’s thumbprint and used this to create the other prints.

“I didn’t even know whether I should accept it or not because it’s really a very amazing gift, but I was very moved and touched,” says Drutt, who also owns a Rothmann brooch made using her mother’s fingerprints.

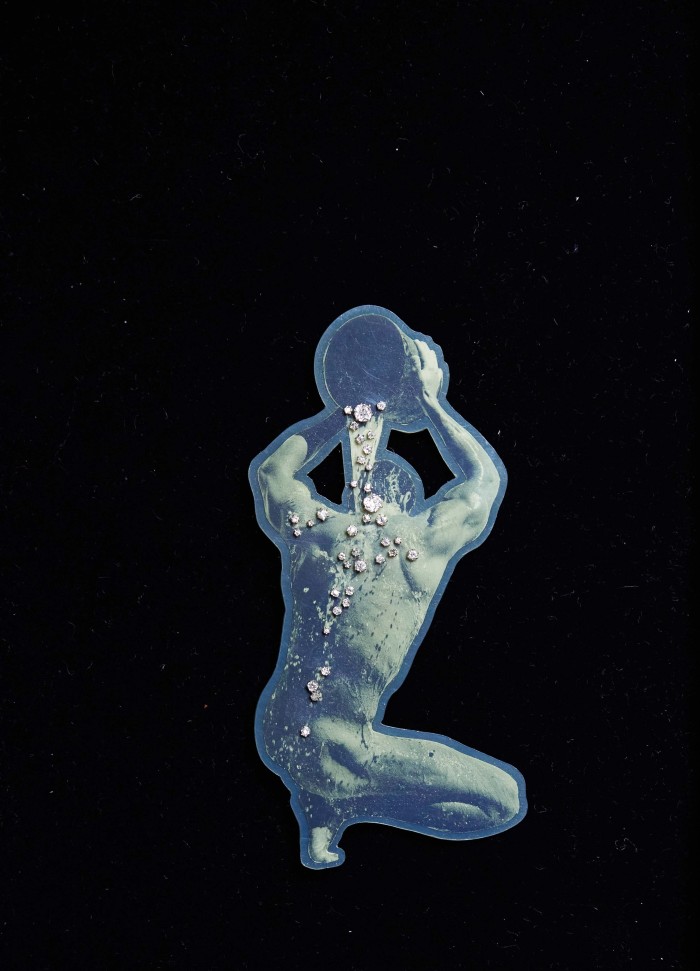

Gijs Bakker Waterman brooch (1990)

It is her mother’s diamonds that feature as water droplets trickling down a man’s back on Drutt’s PVC and photograph brooch, by Dutch designer Bakker. “I love the idea that it really used diamonds in a way that they had never been used before,” Drutt says.

Her mother had split the diamonds from a cocktail ring between her two daughters. Drutt’s “very conservative” sister had her share made into a simple diamond necklace. “[On seeing the designs] my mother simply said, ‘Well that’s the difference between my two daughters’,” Drutt recalls.

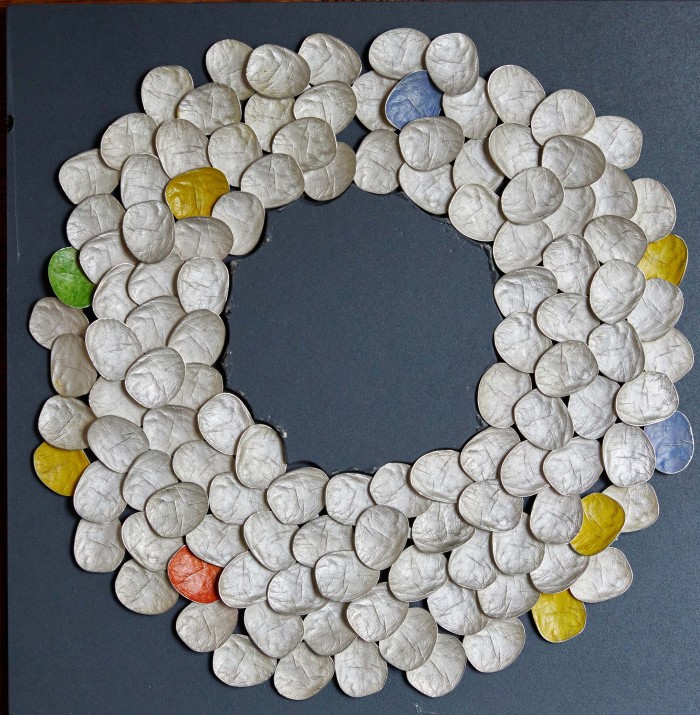

Divine Eye brooch by Robin Kranitzky and Kim Overstreet (2005)

“Gijs Bakker tells everybody that I have an eye,” says Drutt. And this insight provided inspiration for her Divine Eye brooch — a 75th birthday present from its designers, whom Drutt represented at her gallery. The title and mixed material collage refer both to Drutt’s creative vision and to a divining rod.

Drutt thinks she gets her creative eye from her father, who appreciated beauty. He once blindfolded her as a child so she could take in the different aromas of half a dozen roses. “My mother would show us how to make a bed, but my father would tell us which sheets to buy,” she says.

Mirjam Hiller YTENIN brooch (2020)

For her 90th birthday in November, Drutt’s publisher Dirk Allgaier, of Arnoldsche Art Publishers, commissioned this stainless steel and colour brooch from the German designer Hiller. Made from a single flat sheet of metal, it features the number 90 (the title is “ninety” spelt backwards). Covid restrictions ruled out a party, but her children organised a Zoom breakfast for Drutt with 40 friends, including Allgaier. “I just started to cry,” Drutt says. “It was amazing.”

Conscious of her age, Drutt is trying to decide how best to distribute her collection. “I’m nervous about not getting up one morning, but I’d better get up,” she says. “I want at least five more years if I can have it.”

More stories from this report

Maisons back with bold looks to woo buoyant Asian market

UK venture aims to raise the bar on responsible sourcing

Africa looks to polish its credentials in the value chain

Brexit brings hallmark havoc for UK makers

Shaun Leane: All That Glitters proves TV gold for the industry

Black designers gain impetus in year of reckoning

Brands cut to new scenes as red carpets are rolled up

Diamond industry buffs up its image for the young generation

Hard stones are back in fashion

Going back to our past has made Cartier more relevant to millennials, says Vigneron

Jewellers and retailers flock to digital marketplaces

Comments