South African miners modernise to dig industry out of a hole

Simply sign up to the Mining myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

When South Africa’s president Cyril Ramaphosa called the country’s mines a “sunrise” industry last year, it raised eyebrows among observers.

South African mining has long had a reputation as a place where the sun is irrevocably setting. Even for many of Mr Ramaphosa’s supporters, ageing shafts, falling production and a difficult past of labour exploitation and poor safety — particularly in the old workhorses of gold and platinum — seemed out of place in his promised “new dawn” for a battered economy.

Mr Ramaphosa, a mining trade unionist turned tycoon in the industry before his rise to become leader of the ruling African National Congress, has laid a foundation for change by making regulations more predictable and reversing some of the institutional rot in the oversight of mines. But the real test of his rhetoric will come from the industry’s ability to innovate in the face of global challenges.

Over the past century of mining worldwide, the amounts of energy and water required to work the same quantities of rock have risen more than tenfold as the ores within have become more elusive. South Africa, which has some of the world’s deepest mines, is facing a stark social cost if it does not improve the efficiency of its mining.

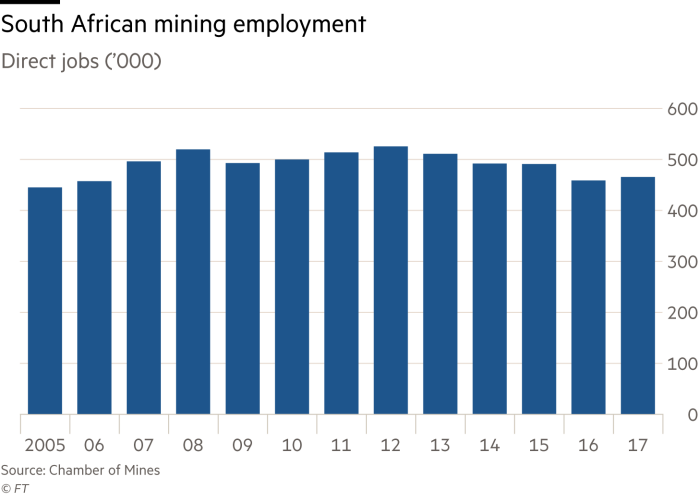

“If we do nothing, if we continue the way that we operate, we could lose at least 200,000 jobs directly,” says Sietse van der Woude, senior executive for modernisation and safety at Minerals Council South Africa, an industry body.

As mineworkers are often the sole breadwinner for several dependants, “you are talking about 2m people who could be affected by that over the next decade”, he adds. That would present a baleful future for a country with a 27.5 per cent unemployment rate — comprising 6.2m people looking for work — and that is struggling to overcome apartheid-era structural blocks on jobs such as poor infrastructure and lack of access to education.

It also reflects why mining remains critical to South Africa’s economy even as its share of economic output dropped to less than a tenth from more than a quarter over the past four decades.

As a result, mining executives say modernisation is not about replacing workers with machines. South Africa in any case does not face the kind of labour shortages that in Australian mines, for example, have spurred the adoption of automated ore trucks and trains.

The focus instead is on training workers while also making technology easy to operate. Another powerful reason for change is a recent increase in deaths and injuries of mineworkers after a long period of improvement. The country saw 88 mining-related fatalities in 2017, up from 73 in 2016 but well down on the 220 recorded in 2007, according to data from Minerals Council South Africa. “A people-centric approach to modernisation is an absolute priority,” Mr van der Woude says.

Out of necessity in a globally competitive mining market, executives say this modernisation is being embraced most in ageing mines. In the next five years, for example, Anglo American will invest $6bn in extending the life of its older mines in South Africa.

“We often refer to it as being dangled over the edge. Sites that are more marginal may be more ready to embrace innovation,” says Donovan Waller, Anglo’s group head of technology.

The company’s wide-ranging FutureSmart programme shows the many elements that can combine to reinforce more sustainable mining than in the past.

In one case, Anglo is tackling a distinctive feature of South Africa’s mining landscape — the “tailing ponds” that are left after separating fine particles of ore from mineral dross, using copious amounts of water.

The company is pioneering processes that tolerate larger particles and therefore allow drier separation. “This is the kind of technology that has multiple benefits. Because we are crushing to a larger size, we also use less energy and have more throughput, bringing major environmental, capital-cost and operating-cost benefits,” says Mr Waller.

In particular, “the process of crushing big rocks into little rocks uses about 4 per cent of the world’s electrical energy. We believe that process is only about 10 per cent efficient,” he adds. “The upside is considerable.”

Anglo is using data and advanced simulations to squeeze more efficiency out of mines, including “digital twin” modelling to understand the innards of machines better before they go wrong. Better sensing also allows Anglo to determine which material in an ore body is worth extracting. “Precision mining is the key to a low-impact future for the industry,” says Rohan Davidson, Anglo’s chief information officer.

While greenfield projects are rarer in South Africa, there is also innovation in unlocking previously inaccessible resources.

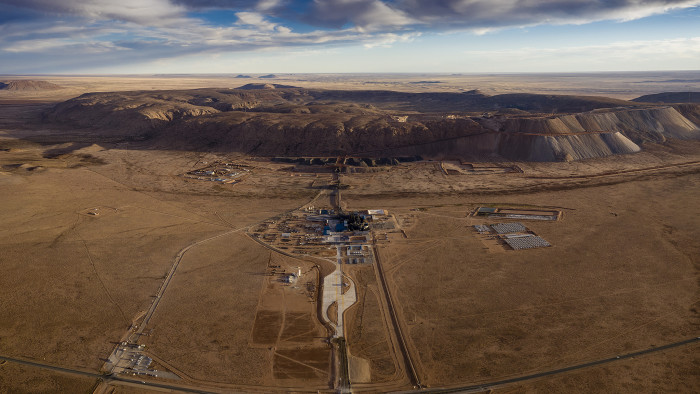

Gamsberg in South Africa’s arid Northern Cape, one of the world’s largest untapped zinc deposits, had long been seen as too challenging to develop. Vedanta bought it from Anglo in 2010.

Partly because the project was launched at the height of a commodity downturn, from the start Vedanta has used digitisation and technology to streamline development, according to Deshnee Naidoo, the company’s South African head.

A “smart ore” system of sensors has helped to identify manganese impurities in the large but low-grade ore body. But innovation can also come in unexpected ways.

Among the greatest achievements on the project so far, Ms Naidoo says, is carefully relocating thousands of plants off the mountain where work is being performed — rare succulents that make Gamsberg a biodiversity hotspot.

An environmental group has monitored the process. “You don’t just tell people you’ve done a good job,” Ms Naidoo says.

Comments