A haven from the storm: pandemic has only increased Monaco’s attractions

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

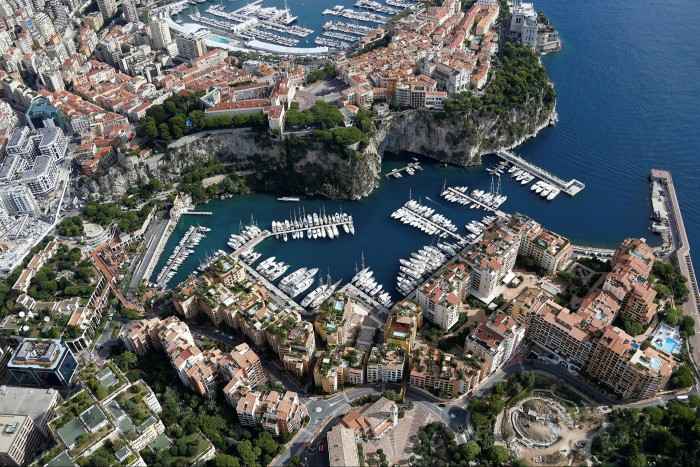

Monaco has long been a comfortable bolt-hole by the sea, free from personal income tax, where wealthy residents can moor their superyachts for fast getaways.

Despite its population density (38,000 people live in just 2sq km), Monaco’s ministers say the pandemic has not dulled the attractions of Monte Carlo and the enclave’s other tightly packed neighbourhoods overlooking the Ligurian Sea on the Côte d’Azur.

If anything, they insist, the worldwide threats of disease, political instability — and ultimately the risk of higher taxes to pay for governments’ deficit-financed economic recovery plans — make a foothold in Monaco more desirable. Since the pandemic began, Evelyne Genta, the ambassador to the UK, says she has been fielding queries from worried London residents about the possibility of acquiring residency.

To understand the increased interest, given the drawbacks of living in a flat during a lockdown — very few of the principality’s costly apartments, with an average price of more than €5m, have private gardens — one has to get a sense of the habits and motivations of the foreigners who have moved here.

They include tennis stars and racing drivers such as Novak Djokovic and Lewis Hamilton, Swedish model Victoria Silvstedt, Israeli shipping magnate Eyal Ofer, Hind Rafik Hariri (daughter of the assassinated Lebanese prime minister and half-brother of Saad, the latest nominee for the premiership he has held twice before), British retail tycoon Philip Green and Jim Ratcliffe of chemicals group Ineos, who moved from Switzerland, as well as thousands of more discreet bankers, lawyers and entrepreneurs. Lionheart, Green’s 300-ft motoryacht, can often be seen in the main harbour of Port Hercule.

With very few exceptions, most residents are not here for the gambling. The belle-époque glamour of the Casino de Monte-Carlo, immortalised in James Bond films and run as a monopoly by the Société des Bains de Mer, is reserved mainly for visiting high-rollers and tourists from Italy and beyond. Monégasque citizens, as opposed to foreign residents, are not permitted to gamble.

In the 19th century, Prince Charles III — who awarded the gambling franchise to businessman François Blanc, the so-called Magician of Monte Carlo — was credited with saving Monaco as an independent state by ceding most of its territories to France, making it what it is today. He abolished income tax — ironically to help the poorer locals, rather than rich foreigners.

Even beyond the confines of the casinos, these days there is little of the sordidly romantic “scent and smoke and sweat” of late-night gambling, as described by Ian Fleming in Casino Royale. Although the late Bond actor Roger Moore was a resident, Monaco’s tax exiles are only occasionally in town to enjoy its luxuries.

Foreigners are obliged theoretically to spend three months a year in Monaco to maintain their residency (rising to six months if they are on 10-year permits) and typically have other homes and estates on the Côte d’Azur, Spain, the UK and further afield. Some residents admit that not everyone always complies strictly with the rules.

“The people who say they live in Monaco have actually all gone to their homes elsewhere,” is the dry comment of one French investor conducting business in the principality during the pandemic. “My impression is that people are largely not around.”

Since succeeding his father, Rainier III, 15 years ago, Prince Albert II and his advisers have worked hard to make the tax rules of Monaco — founded in the 13th century by his piratical Genoese forebears of the Grimaldi dynasty — acceptable to France and the OECD, which leads international efforts to crack down on tax dodging. (French residents of Monaco have to pay French tax.)

Monaco has also courted newcomers who appreciate physical and financial security — and an effective health system — along with zero income tax. The government says just two residents have died from Covid-19 since the beginning of the pandemic.

Officials make no secret of their aim to emulate Singapore (which, like income tax-free Hong Kong, is much bigger than Monaco) as a secure, high-tech hub for its wealthy inhabitants. Monaco is the first country in Europe to roll out 5G telephony using Huawei infrastructure across its territory, and says it has no qualms about data security with Huawei equipment, although few people yet have the new phones to take advantage of it anyway.

“Twenty years ago, Monaco was nowhere on the road map of the rich,” says Hervé Ordioni, who is chief executive of the local branch of Edmond de Rothschild private bank, and heads a committee to promote Monaco as a financial centre. “Now it’s clearly on the map.” Ordioni says the bank’s wealthy customers, holed up in their flats during lockdown in the spring, were furiously trading their portfolios and gave his dealers six times as much trading activity as usual to cope with. “It was massive,” he says.

One Monaco resident who, like his fellow tax exiles, spends most of his life elsewhere in Europe, agrees that the principality has handled the pandemic efficiently and will continue to attract newcomers. “As long as the tax regime is what it is, it will continue to attract people,” he says. “Asians are coming now, Pakistanis and people from Singapore too.”

But he acknowledges the drawbacks of apartment life in a small town, especially for families with children, and bemoans the relentless infrastructure projects to reclaim land from the sea and improve road tunnel links to France.

“We have to escape from Monaco from time to time because it is just a construction site,” he says, echoing the complaints that Hongkongers have about their own city during building booms. “There is only so much drilling you can put up with. The very rich just sit on their big boats.”

Still, Monaco’s constraints do not seem to have diminished its attractions for Britons, Italians and others appalled by the way their own governments have dealt with the pandemic. “Monaco became even more attractive thanks to this,” says one Monegasque financier. “People are coming here and seeing it as a refuge, for security.”

That is certainly the view down on the water at the Yacht Club de Monaco, where giant motoryachts — ships, really — jostle for space in the sparkling waters of the Mediterranean with the occasional classic sailing boat.

“The crisis will change things. Yachts will be used differently,” says Bernard d’Alessandri (main image), the club’s secretary-general, who is putting a brave face on the disappointment of Covid-cancelled boat shows and events turned into largely online conferences.

He sees superyacht owners shunning “show-off” purchases and deciding to use their vessels for work as well as leisure as they search for “a place of refuge” in difficult times. “You can use yachts as offices and the whole family can be there.”

But there is a snag for tax exiles thinking of taking their yachts out to sea to ride out the pandemic in a maritime bubble. Coronavirus spreads quickly on vessels such as cruise liners with cramped crew quarters. Several yachts, including Green’s Lionheart, have been subjected to confinement under yellow quarantine flags in port in Monaco after Covid-19 cases were detected on board.

Government restrictions designed to control the pandemic also disrupted the seasonal traffic flow of superyachts between the Caribbean and Europe. Superyacht movements were sharply down in several key Mediterranean markets in the summer (although Croatia was up), according to Stewart Campbell, editor-in-chief of Boat International.

He told this year’s Monaco: Capital of Yachting Experience event that in Florida “there was lots of activity as people escaped to their boats”, while in the Mediterranean it was a case of “lockdowns, restrictions, cancelled charters, and people unable to access their yachts”.

In short, the pandemic has been a blow for Monaco and many of its jet-setting foreign residents. But the impact has usually been more serious in their countries of origin, from whose tax nets they have escaped.

“They [the Monaco authorities] have been pretty successful in keeping the [infection] numbers down,” says Espen Oino, a yacht designer. “I spent 67 consecutive nights in my [own] bed, which I don’t think I’ve done since I was a student. If something does happen, if you do get sick, I’d rather get sick in Monaco.”

A buoyant business

Espen Oino, a naval architecture and offshore engineering graduate of Scotland’s Strathclyde university, moved to Monaco in 2006 and set up a thriving superyacht design business on the waterfront. He says at least two of his clients rode out lockdowns on their superyachts, one around the Bahamas and one in harbour.

This push for ocean-going self-sufficiency, helped by improvements in communications technology, was already under way before the pandemic.

Some of the world’s richest men — most of the yacht owners are male — had already shown interest in (relatively) environmentally friendly propulsion systems and in the type of sturdy yacht that could be used to explore the Antarctic as well as loaf at anchor off Porto Fino on the Italian riviera or near a Caribbean island.

An extreme example of the modern “working” superyacht is REV Ocean, a 183-metre vessel for Norwegian tycoon Kjell Inge Rokke that will be fitted out as the world’s biggest private superyacht and will double as a laboratory and exploration ship “to make the ocean healthy again”. It was designed by Oino, a fellow Norwegian whose past projects have included the submarine-carrying exploration yacht Octopus for the late Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen.

Still, the fact that global superyacht sales, despite a brief dip, have held up well in the pandemic, has more to do with the rich getting richer through the crisis than with a surge of ecologically minded boat purchases by tender-hearted billionaires.

This article is part of FT Wealth, a section providing in-depth coverage of philanthropy, entrepreneurs, family offices, as well as alternative and impact investment

Comments