‘Where in the world can you get a whisky like this?’

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Ardross Distillery sits at the sleepy edge of a Highland hillscape, wind turbines turning on the shoulder of Ben Tharsuinn to the west, and the deer forest of the Kildermorie Estate spreading birch and rowan trees to the east. In the Middle Ages, this was Picts’ country, home to the tough, ancient tribes who held back the Romans. It’s still wildly beautiful today, but not quite wilderness – the surrounding peaks are gentle Grahams, not Munros, and Inverness is a short drive to the south.

When master whisky blender and Ardross chairman Andrew Rankin first visited this spot seven years ago, the hills were blanketed in snow, and a lone farmhouse stood in front of him, empty and derelict: “A wreck.” But straight away, he saw a distillery. “I’m known as being pernickety,” he says. “But if you go somewhere and it looks good, the chances are it’s going to be.”

Rankin had been briefed by a private investor to find the optimal site on which to build a new Scotch whisky distillery, and he felt confident that Ardross’s atmosphere, as well as its practicalities, were right. Whisky is just water, yeast, barley and wood, and the farm already had its own water supply from the private (and man-made) Loch Dubh. “We could have built a distillery in a tin shed at a fraction of the price in a field off a motorway,” he adds, “but it wouldn’t have been the same.”

On the whisky map, Ardross marks the point where distilleries start to thin out heading north, producing the typically heavier, oiler style of “Highlander” single malts. Though hardy terrain by any standard, it has shed much of its native flora and fauna in the past 1,000 years. The Romans called the Highlands the Great Wood of Caledon, and it’s this lost wilderness that the nearby Alladale Wilderness Reserve (which has four lodges where guests can stay; alladale.com) has sought to revive with a huge, long-term rewilding project. Hundreds of thousands of trees, mostly Scots pine, have been planted, and soon varieties such as crab apple and rowan will be added to attract more birds. Hazel will join the forest to encourage red squirrels. Reviving the romanticism of the Highlands is painstaking work. The rewards, such as a recently arrived pair of breeding golden eagles, come slowly.

It’s a similar tale of patience at Ardross. A veteran of the Scotch industry, formerly chief blender for Morrison Bowmore, Rankin had scouted all over Scotland before landing at Ardross Mains farm in December 2015. He and investors embarked on three arduous years of renovation, building a high-specification complex around the outline of the old farmhouse, laboriously reusing its original materials. The total effect, Rankin says, is of a distillery that’s “been there for 100 years”, though on a cold, clear morning the scrubbed sandstone and neat tiles look unmistakably as if long Scottish winters have yet to dishevel them.

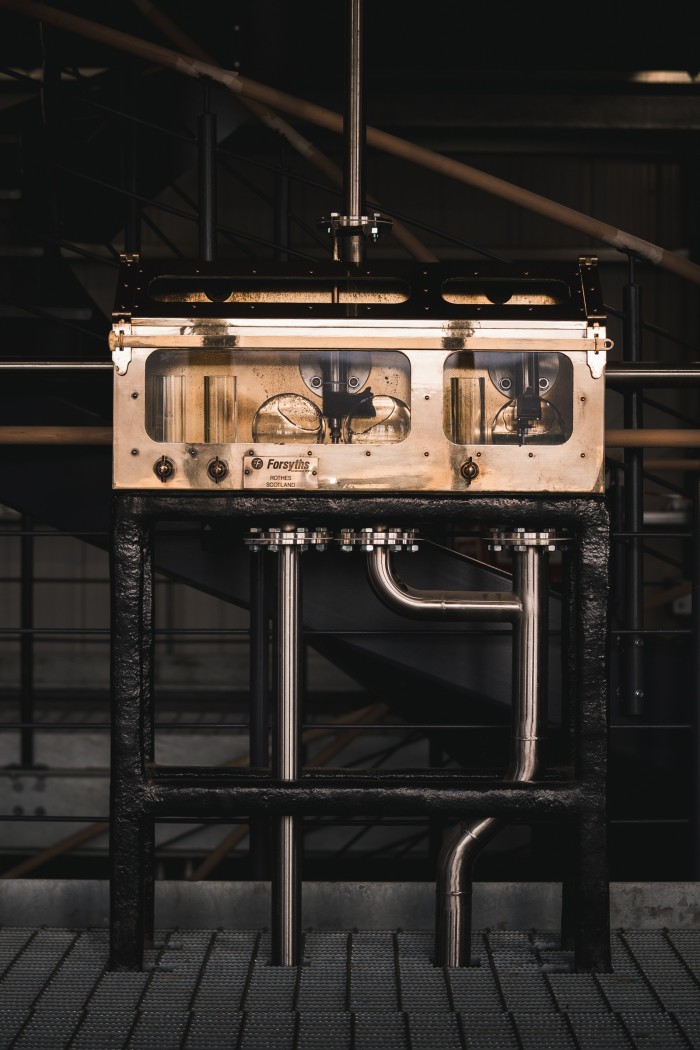

In the main stillhouse, classic single malts have been distilled since late 2019, with a peated malt in production since 2020. But across the courtyard lies something much more leftfield, Ardross’s “creation suite”, a kind of distillers’ Manhattan Project in what was once the cramped farmstead of neighbouring Ardross Castle. This small, end-to-end distillery in the shadow of the commercial site will open next spring with enough equipment packed inside to make almost any world whisky style to order. Other makers have similar “innovation” distilleries in the lee of their main stillhouses, but Ardross goes one up.

“The whole design of the distillery was such that we wanted flexibility to do anything,” Rankin says. “We’ve got a wash still and three different styles of pot still, and a column still which will be able to produce a bourbon or rye or grain spirit style, and a mash cooker which will allow us to process any kind of grain as a base. With all that coming together, it’s unique to the industry, almost like building a customised car.” In the crowded, history-drenched world of Scotch, this will make a valuable distinction for newcomer Ardross. Where else in the world, the thinking goes, can you come to order your own, bespoke cask of whisky, and have a master blender carry out your wishes?

It won’t come cheap – prices start from $10,000 for a customised cask, and only 250 casks will be made from the mini distillery each year. Even so, Rankin admits, “It’s not so much for a revenue-generating purpose.”

Ardross has deep enough pockets. Some £50mn will have been spent by the end of the year on the farmhouse distilleries and the acquisition of a bonded warehouse outside Glasgow, which will have its own cask-filling facility and a small hand-bottling plant. No expense spared. “It’s a huge strategic investment for the company, but our asset value is growing massively. I’ve never seen growth like this in the spirits industry,” Rankin says. Owned by private investors, Ardross Distillery is operated by Greenwood Spirits, with Rankin as chairman. A sister company, Greenwood Distillers, was created alongside to market a range of spirits that wouldn’t necessarily require whisky’s religious patience.

For Sandy Jamieson, the master distiller and manager at Ardross, it’s an opportunity that’s worth his daily commute from Aviemore (he passes the time on the road listening to classic Russian plays). “To be involved in making a new spirit was very high on my list before I disappear,’’ he says, describing the small club of people who get the chance to shepherd a single malt right from a distillery’s very first mash. “It’s a great honour.”

In consultation with Rankin, Jamieson decided he wanted Ardross to focus on long fermentation – some 130 hours, which is double the industry standard of about 60-65 hours. Ardross single malt, he says, is “a light spirit for a Highland, it’s more like a Lowland. The sweetness doesn’t appear until 100 hours.” The flavour reference he offers is Rosebank, the Falkirk distillery that closed in 1993 but is itself being revived. Rankin compares it to Auchentoshan, “one of those whiskies that was under-valued, triple-distilled and lighter, fruitier”.

Ardross uses dried yeast, in part to avoid the logistics of liquid yeast storage, and this contributes to the creamy, rich flavour. But even with almost 100 years of whisky-making between them, neither Rankin nor Jamieson know precisely what Ardross will taste like. “With Scotch you’re flying blind,” Rankin says. Each year, the pair have been drawing cask samples to check on progress. “The colour is amazing,” Jamieson says, holding up a glass flask to the light, where a nascent Scotch from an ex-bourbon cask is the same glossy brown as peaty burn (Scottish stream) water.

Rankin says that tasting the samples gave him confidence they were on the right track. “You know straight away it’s going to be a good whisky. We just need the casks to back that up.” He was away in Kentucky at the time of my visit, buying stocks of the ex-bourbon American oak casks that have shot up in price in recent years. “They’re the highest I can remember them being.” Ardross also has a store of prized virgin mizunara Japanese oak casks. (Three of Ardross’s “first fill” casks were recently sold at auction at Christie’s for a winning bid of £245,000.)

Inside the main stillhouse, Jamieson reflects on why Ardross represents so much freedom. There is a style of mass-market whisky-making, he says cautiously, not naming names, in which a single malt can be all but programmed into a computer. “It’s very boring. You’re just watching the screens for something to go wrong.”

When we reach the washbacks on the first floor, Jamieson says they decided against stainless steel in favour of Douglas Fir. “The old guys used to tell me there’s good bacteria and bad bacteria. With wooden washbacks I think you get the good stuff.” (The “old guys” come from his lifelong career in whisky, including his own father, who worked at Glen Grant distillery in Rothes, where the family was based.) Ardross rotates its peat and non-peat distillations every few months, and as the warmth rises at lunchtime towards the end of the run, the sweet, boggy fumes are irresistible. The peat, like the Simpsons’ malt, is Scottish. When I ask Jamieson what he thinks about “terroir” in Scotch, given that some distilleries ship in non-Scottish barley, he says it’s not just the ingredients. “It’s also the climate and the knowledge.”

Back outside the distillery, Jamieson stands with a cup of coffee chatting to Barth Brosseau, one of the directors of Greenwood Distillers. (Brosseau is also part of Ardross’s team.) Steeped in the viticulture of his hometown Bordeaux, but now based in London, Brosseau is keen not to tread on the elder Scotsman’s toes. “Not any young idiot, French or otherwise, can come and pretend to produce great whisky,” he says. Brosseau anticipates that Ardross will be in “negative cash flow for at least 10, 15 years”. But he adds: “We’re lucky we have serious investment, and don’t have to sell liquid to the blended Scotch markets. The only way to exist is to be fully independent.”

The pair raise their cups to the groundskeeper tending the manicured distillery garden, which is complete with cherry saplings in homage to Japan, another country with a great whisky obsession. By the time the cherry trees are fully grown, the malts will still be maturing in the warehouse. But this is one of the attractions of whisky – that time invariably brings rewards. For Jamieson, the long-termism innate to whisky is also an education. “I’ve been at this 42 years,” he says, “and I’m still learning.”

Comments