Rustbelt renaissance: Pittsburgh becomes an FDI standout

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Pittsburgh long symbolised America’s rustbelt, that stretch of the industrial midwest and north-east that once boomed with steel, cars and coal. In recent years, however, the city has been trading a rusty reputation for a robotic sheen.

Still known as the Steel City despite no working steel mills, Pittsburgh has the muscular look of an industrial-era American city, its downtown jutting proudly above the confluence of three rivers that once served as a primary thoroughfare of national commerce.

Indeed, the city of 300,000 in western Pennsylvania is also known as the City of Bridges for the many examples spanning the Allegheny and Monongahela Rivers, which flow into the Ohio.

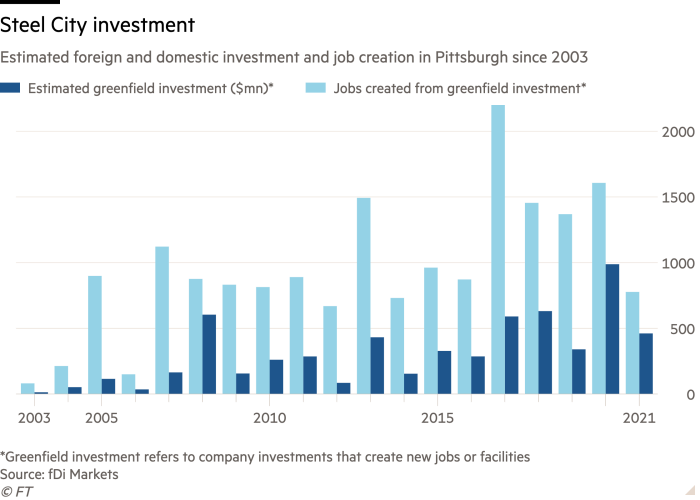

Despite its national reputation as a city that reached its prime more than a century ago, Pittsburgh finished 15th in the inaugural FT and Nikkei Investing in America ranking of the best US cities for overseas businesses, wedged on the list between the hip and techie Austin and Portland.

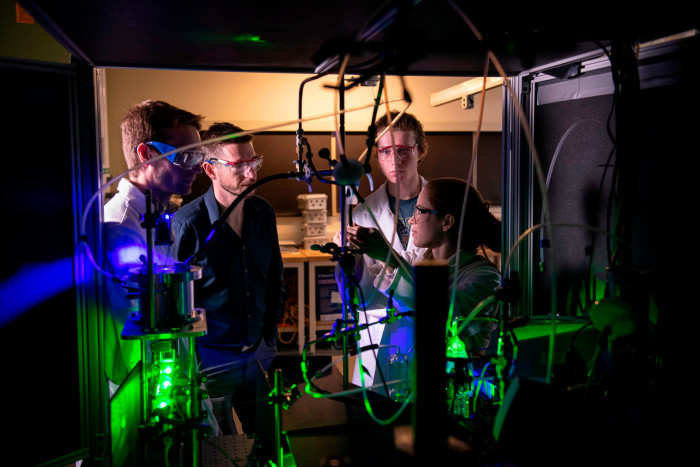

The most-cited motive for investment there is the availability of a skilled workforce, according to data from fDi Markets, an information provider owned by the Financial Times. These skills often radiate from Carnegie Mellon University, a few miles from downtown. The product of two predecessor institutions founded in the early 20th century, CMU is today world-renowned for its computer science and robotics programmes.

Indeed, much of Pittsburgh’s renaissance is built on the foundation of its industrial-age prowess. “We were the Silicon Valley of the Industrial Revolution,” says Dave Mawhinney, executive director of CMU’s Swartz Center for Entrepreneurship.

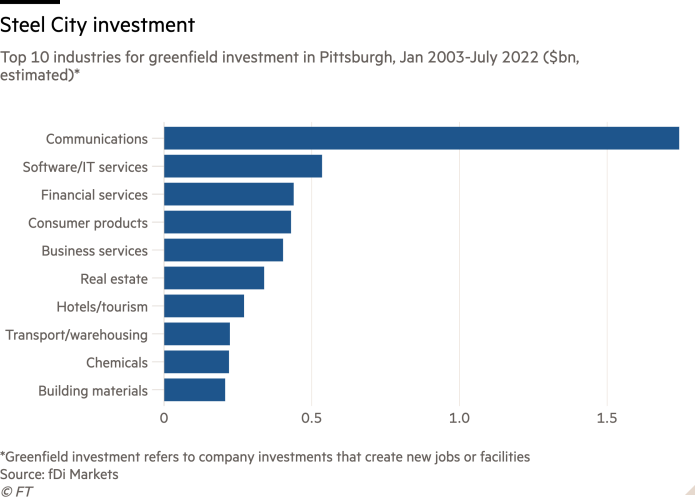

Western Pennsylvania both extracted and produced the materials that powered that revolution: coal, oil, glass, Carnegie steel. Thanks to CMU, it went on to have the materials needed for the digital revolution: commercial computers, robotics institutes, artificial intelligence labs. Google, Facebook, Amazon and other big tech companies have set up shop to tap the associated human capital, Mawhinney says.

“Pennsylvania’s rich history of innovation is one of the best things about the commonwealth, and our world-class research institutions and universities are some of its greatest assets,” Tom Wolf, governor of Pennsylvania, said earlier this year. In August, Wolf announced a tax cut for businesses in the state, where corporate income taxes are the second-highest in the country.

Last month, Pittsburgh hosted the first Global Clean Energy Action forum, convening global leaders to discuss the green energy transition, a significant source of foreign direct investment into the US.

“Pittsburgh is the city that built America,” said US energy secretary Jennifer Granholm, adding that it exemplifies “how a legacy energy and industrial-dependent economy can be transformed into a technology and innovation powerhouse”.

There are challenges. The airport is wanting for direct flights to key destinations, native capital is in short supply, and the city’s smokestack reputation can be a burden.

“People still have the image of the steel mills and the smoke-filled air,” says Mark Anthony Thomas, president of the Pittsburgh Regional Alliance, a non-profit economic development group. “Manufacturing is still very important, and crucial to our economy, but when you visit it’s a beautiful, green, charming place. When people see that they’re immediately transformed.”

Thomas points to activity in robotics, AI, advanced manufacturing and climate technology, noting that the city is home to both overseas engineering giants — such as Germany’s Bosch, which has a research centre there — and successful homegrown start-ups, such as space robotics company Astrobotic and language app specialist Duolingo, Pittsburgh’s first “unicorn”, as billion-dollar start-ups are known.

Other companies are being drawn in. Tata Consultancy Services, the Indian multinational, opened a research centre in April that will focus on AI and the internet of things. CMU now has a TCS Hall, following a $35mn gift from the consultancy.

“Our company has always been focused on hiring people from universities and they tend to grow with the company,” says Suresh Muthuswami, TCS’s North American chair. “So wherever we look to invest, we look for a strong university presence.”

Also catalysing the city’s tech sector are groups such as the Pittsburgh Robotics Network, whose executive director, Joel Reed, argues that the city benefits from an ingrained civic culture of engineering. “If you’re in robotics, you need to come to Pittsburgh,” he says.

A pivotal moment, he adds, was the arrival in 2015 of Uber’s Advanced Technologies Group, which specialises in autonomous vehicles and contributed significantly to the city’s tech ecosystem. Reed’s network estimates that Pittsburgh is home to 105 robotics companies.

The communications sector has benefited from heavy investment too, notably from video conferencing company Zoom, which opened research centres in Pittsburgh and Phoenix, Arizona, in May 2020.

In announcing the move, chief executive Eric Yuan referred to the cities’ “incredibly well-educated, skilled and diverse talent pools” and said Zoom was planning to hire 500 software engineers “drawing largely on recent graduates of the many local universities”.

In the past, many of those graduates would not have hung around long enough to be hired: brain drain was a persistent problem. “Every year, 3,000 of the smartest people in the world come to Pittsburgh,” Mawhinney says. “Before 2006, we exported them all to the Bay Area, or to New York City, or where they came from, like India or China. But when AI and robotics started to come of age 15 years ago, we started to retain a lot of that talent.”

Thomas, who moved to Pittsburgh from New York, thinks that companies may likewise see advantages in smaller cities as they respond to increasing costs and the prevalence of flexible work as result of the pandemic.

“In a post-Covid world the smaller markets have a greater opportunity now to really position themselves for FDI,” he says. “We want to make sure that we’re teed up to take advantage of that.”

Comments