Brands weigh cost against popularity of watch fairs

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Is the watch fair debate finally over? Organisers and exhibitors seem to think so. After years of mud-slinging and uncertainty — peaking with the very public demise of the Baselworld Swiss megafair — the clock may no longer be ticking for the survival of the watch show. But, while the dust has settled, divisions remain.

“There is big momentum in Watches and Wonders,” says Matthieu Humair, chief executive of the Watches and Wonders Geneva Foundation (WWGF), the non-profit organiser of what is now Switzerland’s only major watch fair, opening on March 27. “It’s the fashion week of the [watch] industry.”

Rolex, Patek Philippe, Cartier and Tag Heuer will be among the exhibitors at this year’s event, which is expected to break attendance records. The 2022 gathering recorded almost 22,000 visitors but, unlike last year, the fair will now be open to the public at the weekend, when Humair expects 10,000 paying customers to show up.

Last year’s fair was closed to the public but, following an outcry from exhibitors and the success of watch events designed to reach outside the industry — such as the biennial Dubai Watch Week hosted by retailer Ahmed Seddiqi & Sons — the foundation has changed tack.

“We want to involve the general public and talk about watchmaking not only in Palexpo [the host convention centre] but in Geneva,” Humair says. Tickets to the public days will cost SFr70 ($76), which could bring in meaningful revenues but, given exhibitors are paying millions, the impact on the organisers’ bottom line may not be as significant.

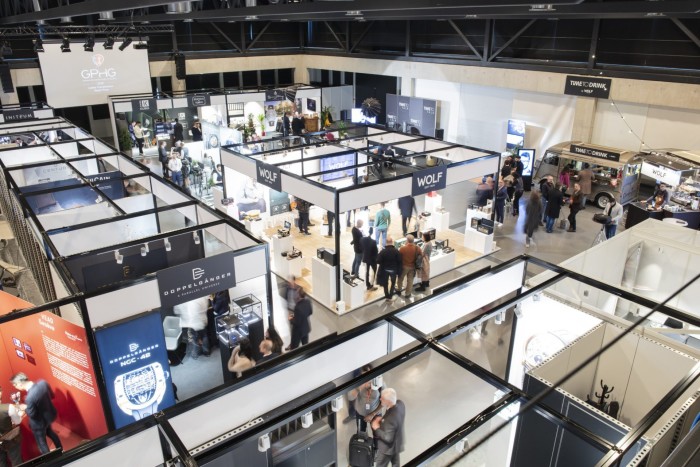

Over the same week, another fair called Time to Watches will also return to Geneva. Last year’s debut event attracted 36 smaller watch brands, such as Corum, Vulcain and Louis Erard.

Exhibitors believe the tide has turned. “Before the pandemic, everyone was questioning the fairs,” says Jean-Marc Pontroué, chief executive of Panerai, one of the Richemont group of brands exhibiting in Geneva. “There was a general agreement and, to be cool, you had to say the show was useless. But we need this.”

Some critics admit they got it wrong. “I was convinced that, after Baselworld, the brands would go over to digital content,” says Oliver Müller, founder of Swiss luxury consultancy LuxeConsult. “But the first W&W . . . that happened digitally . . . was a disaster. Even technology-driven brands like Apple or Tesla need public events to create an atmosphere. Fairs still can create the magic of physical encounters.”

If shows such as W&W are now useful, it is because they have reorganised. The old-fashioned business-to-business sales model is all but gone, replaced by a stronger focus on the end consumer.

“Today, I don’t care about the sales results, because I have them before the show starts,” says Pontroué, adding that the Geneva fair costs him “millions” and is one of his business’s “top three investments for the year”.

“What I care about now is the press and media coverage,” he says. “I have that feedback every day [at the fair]. And it pays for the investment in W&W Geneva big time. The fact you have one show gives you a magnitude of coverage you wouldn’t otherwise have.”

Other exhibitors share his view. “It’s a nice stage to show what we do and it’s very positive in terms of image to be there,” says Julien Tornare, chief executive of Zenith, one of three LVMH watch and jewellery division brands that will be at Geneva. “That’s what we pay for.”

But, despite newfound confidence in watch fairs, plenty are staying away. Some brands that exited Baselworld and W&W’s precursor, the Salon International de la Haute Horlogerie, before the pandemic are yet to return.

Audemars Piguet, Richard Mille, Breitling and the Swatch Group of brands, which includes Omega and Longines, have stayed away. Swatch Group left a gaping hole in Baselworld five years ago, when its chair Nick Hayek famously stated he had better ways to spend $50mn.

Another W&W outlier is Bulgari, which will be exhibiting in Geneva at the time of the show, but not as part of it.

“W&W remains a high-cost event,” says Bulgari chief executive, Jean-Christophe Babin, who also exhibits at LVMH Watch Week each January and was the founder of Geneva Watch Days, a decentralised mini-show attended by around 20 brands that is scheduled to run for a fourth consecutive year this August. “My three events cost me about half what W&W would cost me. And we gain total freedom of doing what we want.”

Babin also says he will not exhibit at the event while LVMH is excluded from the board of the WWGF, which was established in October by Rolex, Richemont and Patek Philippe. “The question is more whether the foundation is ready to acknowledge LVMH as a major actor in watchmaking and, as a consequence, whether it deserves the space and influence a major player should have in that organisation,” he says. “If those conditions were met, probably there would be an opening on our side.”

According to Humair, there are no plans to extend an invitation or to change the board’s make-up. Big exhibitors are invited to join an organising committee, but not the board.

Some analysts have suggested Babin’s demand is unreasonable, though. “LVMH is not a member of the board because it does not need the fair,” says Astrid Wendlandt, editor of luxury news site Miss Tweed. “It has its own events for which it masters expenditures, timing, format and communication.”

Others appear closer to a return. “Audemars Piguet could easily go back if the format were to be changed,” says François-Henry Bennahmias, the company’s outgoing chief executive, adding he would like to see more frequent client-focused events organised during the year in east Asia, the Middle East and the US, as well as Geneva. AP pulled out of SIHH after the 2019 event. It now mixes online launches with in-person presentations, either at its manufacturing centre in Switzerland or in its global network of what it calls AP Houses.

Bennahmias says that, while he is in favour of a fair, his conditions are unlikely to be met. “The whole watch industry should be involved and we shouldn’t see different fairs where one brand is going this way and the other one’s going that way,” he says. “It should be everyone under the same roof. ”

Humair says he would love nothing more. “All year long, each brand can do their own initiative, but for one week they have a common project with the same mission to talk together about watchmaking,” he explains. “This is for future generations.”

Is the debate over? “I hope it is,” says Mark Toulson, head of watch buying at retailer Watches of Switzerland Group. “Rolex and Patek Philippe see the value in it, and smaller brands piggyback on that. They all want to promote mechanical watchmaking and drive interest in the whole industry.”

Zenith’s Tornare believes brands need to take a long-term view. “We want to make sure future generations are interested in mechanical watches. So my dream would be to have a large-scale event where everybody can join.”

Some believe it’s simpler than that. “Selling luxury is all about relationships,” says Rob Corder, founder of the London event WatchPro Salon. “That will include WhatsApp and social media but, if 2022 taught us anything, it is that people want to spend time with others with shared passions.”

Comments