When fridges attack: why hackers could target the grid

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The owner of a smart washer-dryer might consider a breach of the machine by hackers more inconvenient than dangerous. Yet according to new Princeton University research, cyber criminals gaining control of thousands of high-wattage networked home appliances could launch a co-ordinated attack that would shut down the power grid.

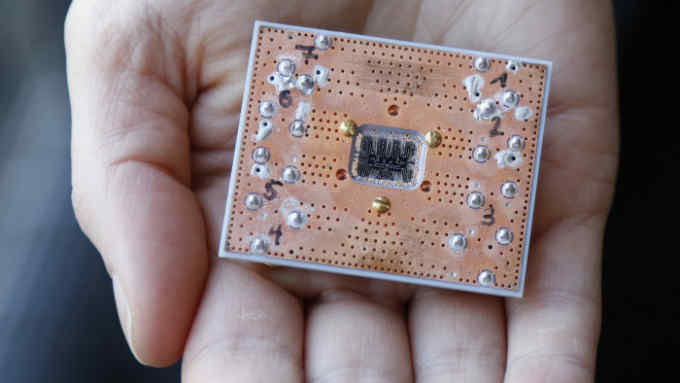

As manufacturers connect everything from TVs and fridges to air-conditioners via the internet of things (IoT), they are creating new vulnerabilities. Rather than having to penetrate the sophisticated cyber defences of businesses, criminals can now use IoT’s weakest links: products and appliances with poor security protections or none at all.

Many consumer goods manufacturers have yet to invest in security measures, says Martijn Verbree, a partner in KPMG’s cyber practice. “It’s new territory for them,” he says.

Researchers presented a paper in August at the Usenix Security Symposium in Baltimore, demonstrating a potential attack. Dubbed MadIoT (manipulation of demand via IoT), it allows criminals to compromise the power grid without needing to breach the highly protected control systems of utility companies.

Instead, a MadIoT attack would manipulate demand. In a simulation of a small-scale power grid, the Princeton researchers found that a 30 per cent spike in demand would shut down all generators in a targeted area. A hacker could create such a spike by taking control of about 90,000 air-conditioners or 18,000 electric water heaters.

Such large numbers of connected products are becoming a reality. Gartner estimates that by 2021 homes globally will contain more than 15bn connected devices, up from 4.8bn today.

The ability for criminals to turn IoT products into weapons was highlighted in 2016 when a botnet (a group of connected devices) called Mirai used hundreds of thousands of cameras, routers and digital video recorders to overwhelm a key internet server with high volumes of traffic. Known as a distributed denial of service (DDOS), Mirai shut down the websites of large companies for several hours.

“It’s the equivalent of a cyber army of controlled devices attacking some of the core services that form the internet,” says Justin Lowe, a cyber security expert at PA Consulting.

Today 40 per cent of smart home appliances globally are being used for botnet attacks, according to Gartner, which estimates that this will rise to more than 75 per cent by 2021.

Vulnerabilities in smart home appliances pose risks for their owners, too. Poorly secured household devices could be a route in to more sensitive equipment such as a personal computer. Devices can be used to spy on their owners, particularly when equipped with cameras or microphones.

“Even your thermostat could be used by criminals to know when you are at home and when you normally arrive,” says Mr Verbree.

Another challenge for consumers is keeping product security current. While the tech sector offers regular updates and patches for its devices, manufacturers of home appliances often lack the expertise to develop these.

Yet when it comes to smart products, manufacturers’ responsibility now needs to extend long after making a sale. “There’s been a go-to-market drive to get cash flow,” says Paul Dorey, chairman of the IoT Security Foundation. “They sell a product at a certain cost. But having to maintain it for the next 10 years is not something that enters their thinking.”

There are few off-the-shelf cyber security products available for the manufacturers of home appliances, Mr Lowe adds, meaning that expensive customised solutions have to be used. “It’s not often cost-effective to deploy that in a fridge,” he says.

In an effort to help manufacturers improve the security of their products, the IoT Security Foundation is developing free industry guidelines. Professor Dorey also suggests that many products may need to come with a subscription to a security service.

Meanwhile policymakers are exploring regulatory frameworks to cover connected home appliances. In the UK the Department for Culture, Media and Sport’s Secure by Design review calls for shifting the burden from consumers and requiring security to be embedded IoT products. The UK is also considering the regulation of smart appliances.

Even if regulation is not immediately brought in, companies will need to invest to protect their brands.

“Anybody producing IoT-type devices needs to think about what they’re doing and understand the wider risk of how their systems could be misused,” says Mr Lowe. “Because it could come back to bite them from a reputational point of view.”

Comments