US cities fight to attract foreign investors’ money

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

For much of the 21st century, the US has been the undisputed champion of attracting foreign investment. Despite a Great Recession and spates of political dysfunction, multinationals from around the globe continued to pour money into the world’s largest economy, an influx that swelled to a record $468bn in 2015.

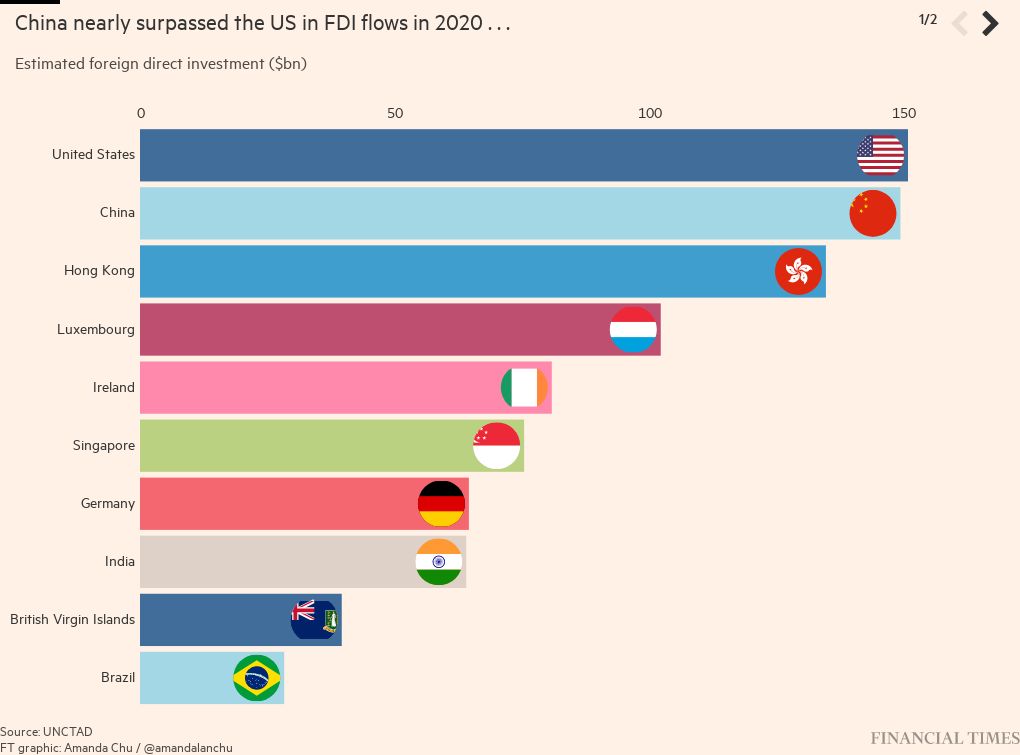

But in the pandemic-stricken year of 2020, the US nearly lost that crown, according to data compiled by the UN. China, which had been slowly gaining on its American competitors, came within $2bn of claiming the top slot, prompting hand-wringing in the US over whether the fast-growing, rising Asian power would permanently supplant its geopolitical rival.

“It really caused huge competitive issues for the United States,” says Patrick Dine, chief executive of PSD Global, an international business consultancy, adding that China’s rise sparked “political pressures” to reverse the trend.

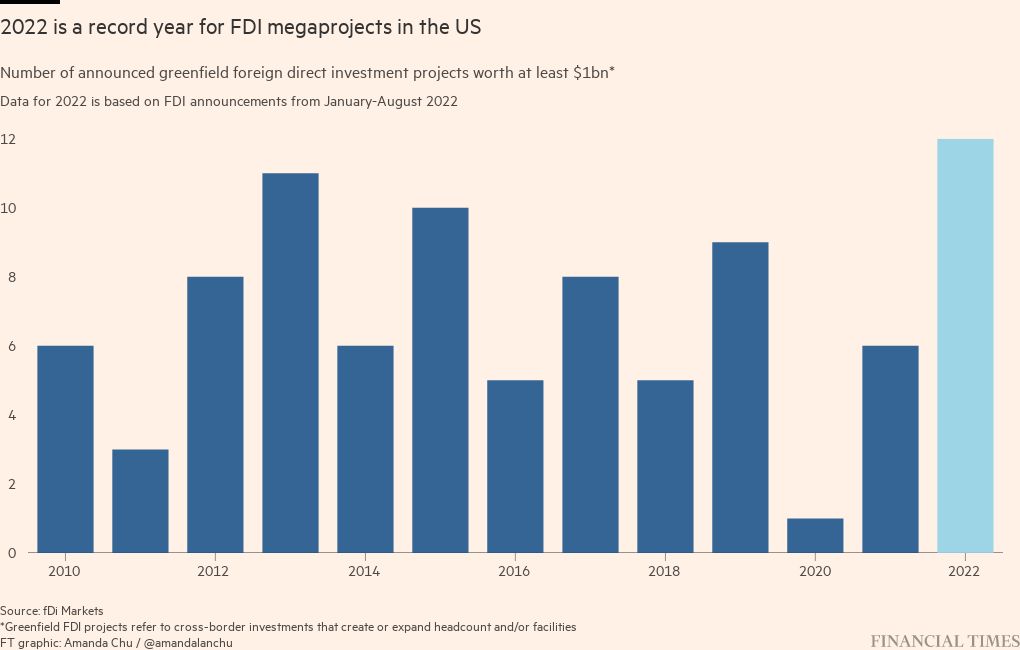

Last year, with China struggling to maintain its “zero Covid” strategy, the US was easily back on top, surging to $367bn in foreign inflows — more than double the $181bn taken in by the Chinese economy. And 2022 is shaping up to be another banner year, with at least 12 “megaprojects” — investments worth at least $1bn — announced by overseas investors in the US, totalling $34.9bn in capital expenditure, according to data from fDi Markets, an information provider owned by the Financial Times that tracks greenfield foreign direct investment, or cross-border investments that create new jobs and facilities.

“There is definitely a lot of uncertainty right now in the United States,” says Nancy McLernon, head of the Global Business Alliance, a trade association representing the largest foreign multinationals in the US. “But when I talk to executives at my member companies, they’re feeling bullish.”

Still, the shock of 2020 has led many American cities and states to redouble their efforts to attract foreign capital, no longer complacent that the sheer size and dynamism of the country’s economy is enough to convince overseas executives to pick the US for their next investment dollar.

That increasingly competitive scramble for foreign capital has prompted the FT and Nikkei — two of the world’s leading chroniclers of cross-border investment — to compile the inaugural Investing in America ranking, a data-driven tally of the best cities in the US for foreign companies to do business.

Many of the metrics the FT and Nikkei used to measure cities are the same a domestic company would consider to decide where to invest: a skilled workforce, for instance, appeared in nearly a third of US project announcements from foreign investors last year, according to fDi Markets.

“Every site we pay for, we want to make sure it’s successful — and that success starts with its labour force,” says Tim Ingle, chief financial officer of Toyota North America, which moved its US headquarters to the Dallas region in 2017 and this year broke ground on a $1.3bn battery plant near Greensboro, North Carolina — an investment that was supplemented by an additional $2.5bn announced in August.

But the FT and Nikkei also examined attributes that would specifically attract overseas investors. How many international flights leave from nearby airports? How much do local economic development authorities help companies with requirements such as visas once they set up shop? How many foreign-born nationals live in the region? (For more details, read our methodology.)

Unsung heroes

The top 20 cities in the FT-Nikkei ranking secured nearly a third of all new FDI projects announced in the US last year. Some have long been hailed as multinational hubs. Miami, the winning city, has been a gateway to Latin America for half a century and has secured more than 70 new projects from the region in the past decade, according to fDi Markets data.

Other cities ranked surprisingly well despite not winning marquee projects — Jacksonville, Pittsburgh, Kansas City — because they have created a business environment where foreign companies can prosper.

The Toyota investment is a sign that North Carolina has become something of a hub of such cities, joining others in the south-east with pro-business labour laws and low corporate taxes. The state has three in the FT-Nikkei ranking’s top 20 — Charlotte, Raleigh and Greensboro — with executives citing the state’s lower cost of living as a key driver.

Kim Sneum Madsen, chief executive of Danish tech group Umbraco, says his company chose Charlotte for its US headquarters in 2020 after looking at five other cities, including Chicago, Austin and Philadelphia, because of a low cost of living as well as an airport with multiple nonstop flights to Europe and fewer large tech groups competing for talent.

“I must admit, I didn’t know Charlotte beforehand,” Sneum Madsen says.

Other, smaller US cities have become targets for foreign investors because of a low cost of living, including lower taxes and cheap rents. Louisville, Kentucky, which finished 30th on the FT-Nikkei list overall, came in first in our “business environment” category; office space in the city averaged $19.37 per square foot in 2021, less than a third of the cost of space in New York, Boston or San Francisco, according to data from CommercialEdge, a property information platform.

Similarly, the small town of Taylor, Texas, secured last year’s largest FDI commitment: a $17bn chip deal with Samsung. The production site will span over 5mn sq m, making cheap real estate and low operating costs paramount.

“The perfect location is probably something you’ve never even heard of,” says Didi Caldwell, president of Global Location Strategies, a site selection consultancy.

Big is beautiful

Still, the US’s biggest, most cosmopolitan cities performed well on the FT-Nikkei ranking. In addition to Miami, three of the five top finishers are among the US’s largest and most storied cities: New York, Boston and Houston.

Despite higher costs for doing business, these metropolitan centres shine when it comes to deep talent pools, openness to expatriates, and other specific needs of foreign multinationals, like major ports and airports.

New York, for example, has more than 320 universities within a 50 mile radius, according to GIS Planning, an FT-owned corporate location specialist, which means companies there have multiple pipelines for training and recruitment. Houston has the largest shipping port in the US by waterborne tonnage, and over half of Miami’s population is foreign born, the most of any large US city.

“We have all of the infrastructure for international,” says Susan Davenport, senior vice-president and chief economic development officer at the Greater Houston Partnership, a business association. “We have that great talent base, and we love the fact that we’re an international city. We celebrate that.”

Increasingly, though, cities and regional development agencies have been forced to become more proactive to secure the big foreign investments that, in the past, almost came unsolicited.

Not only do foreign companies seek tax breaks and incentive packages, but they also are increasingly looking for “aftercare” — the term used to refer to a range of services, including help with visas and navigating unfamiliar regulatory hurdles, offered to companies once they arrive in the US — provided by some municipalities.

Savannah, Georgia, is a case in point. In May, Hyundai announced it would build a $5.5bn electric vehicle plant in nearby Bryan County. But that deal was secured only after the state spent years wooing South Korean companies, including Kia, which built its first-ever US assembly plant in the city of West Point. In addition to identifying a large parcel of land for the plant, regional authorities had work-training programmes at the ready to ensure a skilled workforce.

“FDI is about relationships,” says Pat Wilson, commissioner of the Georgia Department of Economic Development. “These are long-term relationships. They’re investments in the future.”

Comments