Why did the Lesedi la Rona diamond fail to sell?

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

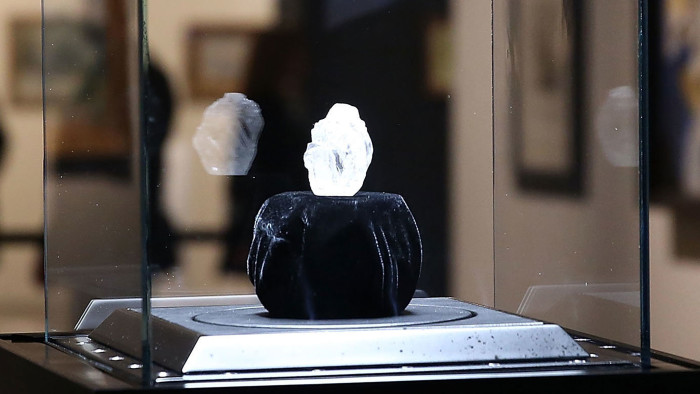

“This is a historic rough diamond,” said David Bennett, worldwide chairman of Sotheby’s jewellery division, as he prepared for a much-heralded sale in June: the auction of the Lesedi la Rona, a 1,109ct stone found just months earlier in Botswana. “We have had the most extraordinary response when we have taken it around the world.”

Shortly after, the sale was over — but it did not end as most in the room had expected: Mr Bennett brought down his hammer after bidding stalled at $61m, missing the reserve. His next words were heard in silence: “Sadly, the Lesedi la Rona was not sold.”

What had gone wrong? The price of $61m, more than $68m with the buyer’s premium, was not inconsiderable but it had clearly not been seen as enough for Lucara Diamond, the mining company that had unearthed the stone at its Karowe site. While no reserve had been announced, many in the industry had estimated a figure of at least $70m.

The auction was held a few days after the referendum in which the UK voted to leave the EU, hitting UK shares and sterling and shocking global markets. Talking shortly after the sale, William Lamb, chief executive of Lucara, believed that the decision may have had an effect: “We don’t know what the future economic outcome is going to be for the people in that room.”

But Mr Lamb also thinks the auction itself represented an unpopular challenge to the way diamonds of this type have been traded. Lucara’s decision to sell the Lesedi la Rona in this way was an attempt to explore an alternative sales avenue for such stones — one that would have attracted wealthy buyers who saw the rough diamond as akin to a rare work of art. It is very different from the typical process of selling large rough stones in private deals or tenders to diamantaires, who can then cut the stone to order.

Lucara challenged this established process because it felt it had to, says Mr Lamb. The Karowe mine is renowned for producing large diamonds, and opening up a “new pool of capital” from wealthy individuals was seen as vital for selling further large stones.

“We could have gone straight to the trade and it would have been sold in no time . . . [but] we wanted to see whether there was a market and whether stones of this significance would be acquired by private collectors,” Mr Lamb explains.

But he believes that part of the diamond trade felt threatened by a method that could have diminished their influence and therefore declined to bid hard.

“We knew what the trade was doing at the auction,” he says. And without a clear lead from diamantaires, say Mr Lamb and other analysts, any non-trade buyers felt less confident about bidding for the stone.

Ed Sterck, an analyst at BMO Capital Markets in London, says: “It is understandable that the diamantaires may see potentially being cut out of the process as not in their best interest . . . although with that in mind it is also not entirely clear how a private buyer would then have the stone cut, although I am sure someone would acquiesce in the end.”

Lucara retains the Lesedi la Rona on its balance sheet and says it is confident of selling it. Mr Lamb adds that the company remains keen to use public auctions — but not now for the largest rough diamond to have been found in 100 years.

“Maybe it shows that that side of the market is not yet mature — we need to do more work,” he says. He repeats the words of Lukas Lundin, the chairman of Lucara who was also present at the Sotheby’s sale: “One hundred years’ worth of history is not something you can change with a single auction.”

Comments