Cross-border investigations help take down hackers

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

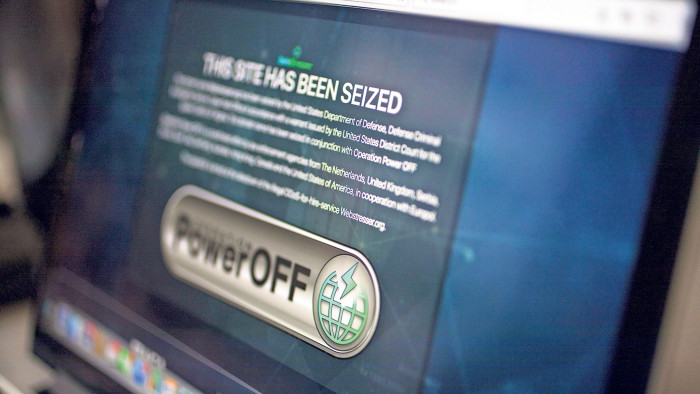

When the authorities closed down cyber attack website Webstresser and arrested its administrators in April, it was the culmination of a complex international investigation.

Operation Power Off was led by the Dutch police and the UK’s National Crime Agency, supported by Europol and a dozen other law enforcement agencies around the world. It was the latest example of increased global co-operation between police forces, as law enforcement agencies search for better ways to counter cyber crime.

Webstresser, which had 136,000 registered users, sold cyber attacks for as little as $14.99, meaning that even those with no hacking expertise could attack a network with little chance of being traced.

Cyber security analysts believe it was used to launch 4m distributed denial of service attacks — where a computer network or a website is bombarded with so many information requests it ceases to function — against banks, governments and other organisations.

Anonymous attackers such as Webstresser’s are difficult to counter, but this operation was an example of what co-ordinated international action can achieve, says Steven Wilson, head of Europol’s European Cyber Crime Centre (EC3) in the Netherlands.

“Another was Operation Taiex in March, which resulted in the arrest in Spain of the leader of the gang behind the Carbanak and Cobalt malware attacks that targeted over 100 financial institutions worldwide,” he says.

“That investigation involved the Spanish national police, with the support of Europol, the US FBI, the Romanian, Moldovan, Belarusian and Taiwanese authorities and private cyber security companies.”

The “game changer”, says Mr Wilson, is the Joint Cybercrime Action Taskforce (J-Cat) hosted by EC3. Set up in 2014, it is a standing operational team of 15 cyber liaison officers from several EU states and non-EU partners, including the US’s FBI and Secret Service, all working out of the same office. They take on the most complicated cases where international collaboration is needed to get results.

In the case of the Carbanak and Cobalt attacks, for example, this involved tracking the activities of coders, mules, money launderers and victims across multiple countries.

The FBI also increasingly works with police forces around the world. The FBI has cyber experts in about 20 US embassies, and has cyber action teams ready to travel abroad at a moment’s notice to help victim companies.

The FBI worked with the Latvian State Police Cybercrime Unit and the Latvian General Prosecutor’s Office to investigate the Scan4you counter antivirus service. One customer used it to test malware that was later used to steal 40m payment card numbers and 70m pieces of personal ID from stores across the US, costing one retailer $292m.

In addition to collaboration with national police forces, EC3, the FBI and Interpol are working with private companies to prevent attacks taking place.

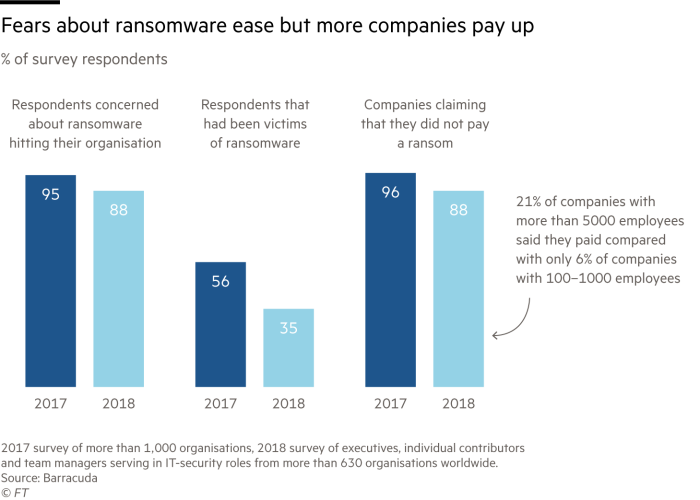

In 2016 the EC3, Dutch police, and companies Kasperksy, McAfee, Amazon Web Services and Barracuda Networks set up the No More Ransom website to advise individuals and businesses how to avoid being caught by ransomware. If they do fall victim, they can upload encrypted files for analysis and, in some cases, decryption.

Interpol, which co-ordinates policing between 192 member countries, meanwhile, is deepening its collaboration with the financial sector.

In May it signed an information-sharing agreement with Banco do Brasil under which a bank employee will be seconded to Interpol’s Global Complex for Innovation in Singapore, where anti-cyber crime activities are centred. This is the first such relationship with a bank.

There is one area where co-operation between police forces and companies is lacking, however: encryption.

The FBI is struggling to get technology companies to provide access to data on encrypted mobile phones, the most famous case being Apple’s refusal to accede to an FBI request to hack an encrypted phone that belonged to one of the San Bernardino killers in 2015.

FBI director Christopher Wray said recently his investigators “were unable to access the content of 7,775 devices even though we had the legal authority to do so”. He described it as a “major public safety issue” and pleaded for the industry to suggest some “constructive solutions”.

Mr Wray wants companies “to respond to lawfully issued court orders” and give the FBI access to devices, “in a way that is consistent with both the rule of law and strong cyber security . . . we need to have both, and can have both”.

Comments