Literary Life: The fantasy worlds of Alan Garner

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

A farmer from Mobberley rides to Macclesfield fair in October to sell his white mare. At Thieves’ Hole he meets an old man who offers to buy the mare there and then. The farmer won’t sell, thinking to get a better price at the market — but he gets no price at all. Returning home with his pockets empty, he meets the stranger once more; now the farmer is willing. Come with me, the stranger says.

“By Seven Firs and Goldenstone they went, to Stormy Point and Saddlebole. And they halted before a great rock embedded in the hillside. The old man lifted his staff and lightly touched the rock, and it split with the noise of thunder.”

So begins Alan Garner’s telling of the legend of Alderley, the preamble to his first novel, The Weirdstone of Brisingamen (1960). The opened rock reveals a pair of iron gates; behind are 140 knights lying in an enchanted sleep, each in silver armour and all but one with a white mare by his side. The stranger — the wizard, as we know him now to be — tells the farmer that the knights will save England when the country is in peril. The farmer’s payment is as much treasure as he can cram into his pockets from the heaps of gold and precious stones that lie in another cave. Then the gates close behind him, and out in the night the farmer is alone near Stormy Point. He never sees those gates again.

The map that serves as the frontispiece for The Weirdstone shows clearly the names of the places in the legend. Many books of fantasy (so-called) provide maps to the worlds they describe; you can find your way through Earthsea, Westeros, Middle-earth. But the creators of those worlds can’t meet you in the car park of a pub (“The Wizard”, of course) and walk with you to the very places in the legend: from Thieves’ Hole by Seven Firs and Goldenstone, to Stormy Point and Saddlebole. That’s what you can do with Garner. In speaking of The Weirdstone he is given to accepting that in this apprentice work he wasn’t really up to the task of character development. What enabled him to write it was rather his intense, emotional understanding of the landscape of Alderley Edge in Cheshire, where his family has lived for generations.

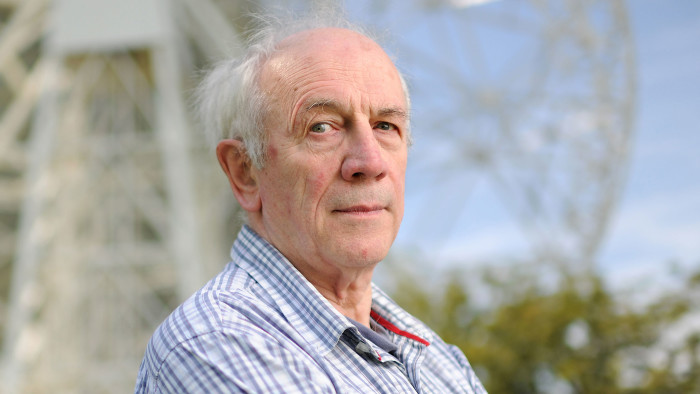

Garner was born in 1934 in nearby Congleton, to a family of smiths and stonemasons. He was a star pupil at Manchester Grammar School, and headed off to Oxford to read classics; he planned to become an academic. But he left before he finished his degree, having decided that the real work he was meant to do was in his native county, just as it had been for his forebears. “I’m like Antaeus,” he told me once — still the classicist. “I put my arm on the earth and my strength returned.”

He was 22 when he started The Weirdstone; that book, and others such as The Moon of Gomrath (1963), Elidor (1965), The Owl Service (1967) and Red Shift (1973), established him as one of the most prominent voices in children’s and fantasy literature, though he doesn’t have much truck with such categorisations. One of the first things Alan ever said to me, at our initial meeting more than 15 years ago, was this: “I feel instinctively that children’s writing can’t be literature. It is ghetto writing. CS Lewis said that if a book can only be enjoyed by children then it’s not a good book. I never considered myself a writer for children.” His later novels, Strandloper (1996), Thursbitch (2003) and Boneland (2012), were all published “for adults”, but it’s worth bearing in mind that it is the publishers who drew that line of demarcation, not Garner.

Look around your local bookshop and you’re bound to see stacks of what has been called “the new nature writing”. Writers such as Robert Macfarlane, Richard Mabey, Kathleen Jamie, Helen Macdonald and James Rebanks — to name just few British authors — have tapped into something we feel we are losing. Fewer and fewer of us, it seems, have a strong relationship with the land through which Tarmac roads are run, upon which cities are built: books such as Macfarlane’s Landmarks (2015), or Macdonald’s H is for Hawk (2014) give readers a return to a greener world.

But Garner isn’t returning to anything; he’s been there all along. So perhaps it’s no wonder that Macfarlane and Macdonald were both keen contributors to First Light, a volume I have edited that celebrates Garner’s life and work. Both acknowledge him as a writer with a special connection to landscape — not something that many people in the hyper-mobile 21st century ever get to feel. And yet it’s a feeling that still resides in us, if we can gain access to it. Who doesn’t yearn to belong somewhere?

In First Light, Philip Pullman writes of a childhood spent moving from school to school; Garner’s Cheshire was a constant in his life. Elizabeth Wein is an American, as I am, but moved to Alderley Edge as a girl, coming to understand it through Ordnance Survey maps — and Garner’s books. Macfarlane has taken one of those OS maps and traced it with the names, real and mythological, that thread through Garner’s stories. No one gets away from the Edge. And no wonder. The Edge casts a spell; it is, as Garner says, a dramatic hill, with a sense of otherness about it. You only have to walk it to feel it, even if you are a stranger.

I was, I am, a stranger. Where Garner’s family have been rooted in one place for centuries, I can’t say the same of mine. Five generations back, my people fled eastern Europe for a better life in the New World. No one knows where they came from, not really; they gave themselves new names, the better to disappear into America and what they believed it had to offer. Thirty years ago I made the journey in reverse, looking for something, even if I didn’t know what it was. When I met Garner and his wife Griselda, I began to see what it might be, even if it could never truly be mine.

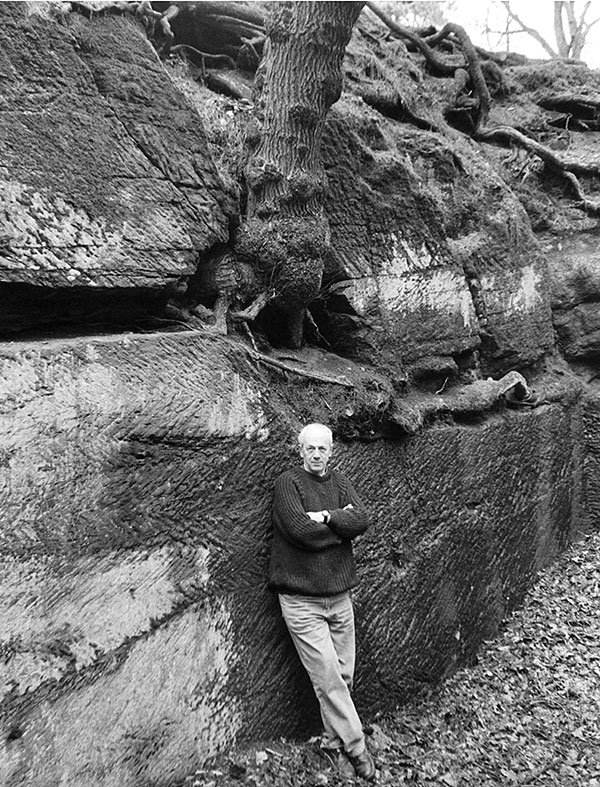

And so I walked with Alan and Griselda — and not just to the Edge, though that was extraordinary enough. There was a trip to Ludchurch in the north Staffordshire Peak District, which you can find if you follow the directions so handily provided in the 14th-century Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. “Thenne gyrdez he to Gryngolet, and gederez þe rake,/ Schowuez in bi a schore at a schaȜe syde,/ Ridez þurȜ þe roȜe bonk ryȜt to þe dale . . . ” Gawain spurs on his horse, Gringolet, picking up a path beside a wood, riding down a rough slope — until, finally, he comes to a cut in the rock, which you will know if you have ever been there. A chasm, but open to the sky, and hung with vines and moss so that it shimmers green with a brilliance I have never forgotten.

Garner’s encounter with the Gawain poet was a real meeting of minds. “I was fortunate in that I did not read Sir Gawain until I wanted to,” he has written. “And, as a native of Cheshire, I was puzzled at so many footnotes. I did not need them, apart from a few technical words that could not be inferred by context; neither did my father when I read extracts to him aloud. He could not have known that I was quoting Middle English. For him, we were doing no more than use our native speech, a speech that caused a well-meaning teacher to wash my mouth out with carbolic when I was six for ‘talking broad’.” In Garner’s most recent novel, Boneland (2012), Ludchurch appears as a place “filled with summer. The ice had gone and the green mist of growing lit the spirit faces that looked out from the walls among fern, grass and holly along the twisting length.”

It was some years after the trip to Ludchurch that the three of us made another journey, this time to Thursbitch, on the occasion of the 2003 publication of the novel by that name. A name which means “the valley of the demon”: in Old English, “þyrs” is a demon; “bæch” is a valley. The novel makes a bridge in time between John Turner, an 18th-century traveller who died mysteriously in the valley, and two modern visitors to the place. Garner told me that when he began to think of writing about the valley, locals advised him not to go (Thursbitch is five miles, as the crow flies, from Macclesfield, and about 20 miles from the Garners’ home; but in these parts local means local). They told him it was “no good place”; they said they would never think of going there themselves. Garner told me all this as we drove there in the Land Rover, and by then I’d known him long enough to understand that he isn’t someone to say this kind of thing lightly — to scare a visiting journalist, as a joke.

We arrived; we parked. That visit is as vivid to me now as the trip to the Green Chapel, but in another way entirely. I hated that place, and the feeling is easily recalled. It was a grey day; the valley felt shut away from the rest of the world. I felt it was necessary to ask permission, once we had entered, to leave. The ridges of the hills closed off the pale sky, and if I close my eyes now I can only recall seeing a track that went deeper into the place, and no way out. No wonder, I thought, and still think, that John Turner was cast adrift here, and died in the snow so close to home. I recalled one of the first email exchanges I ever had with Garner, in which he explained his method to me with characteristic emphasis. “I don’t INVENT,” he told me. “I FIND.”

Erica Wagner will be talking to Neel Mukherjee and Richard Ovenden about the work of Alan Garner at the FT Weekend Oxford Literary Festival on Monday April 4. ‘First Light: A Celebration of Alan Garner’ is published on May 5 by Unbound, £20, theblackdentrust.org.uk

Photographs: Matthew Pover/Writer Pictures; Sefton Samuels/National Portrait Gallery; Alamy

Comments