Soaring UK rents leave tenants facing eviction and homelessness

Simply sign up to the Property sector myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Eye-watering rent increases across the UK are piling pressure on tenants already grappling with spiralling living costs, driving some from their homes and stoking fears that the market is overheating.

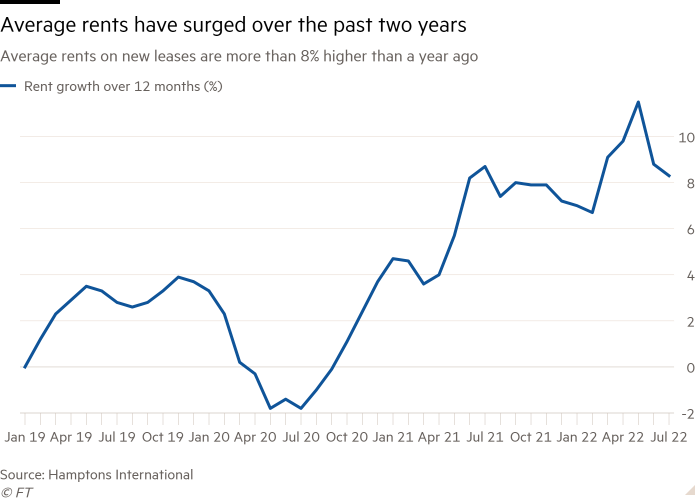

Rents are rising at their fastest pace since the financial crisis owing to a combination of increased demand, slower turnover of rental homes and opportunistic efforts by some landlords to pass higher costs on to tenants.

Average rents on new leases are up almost 10 per cent compared to a year ago, according to estate agent Hamptons International, and a growing number of renters are unable to keep up with payments and facing eviction. Tenant groups warn the market is overheating and that renters face homelessness as a result.

Eva, an Edinburgh university undergraduate student, managed to negotiate her 35 per cent rent increase down to 20 per cent, but will still be priced out of her home. “We have to move out in two weeks and we literally can’t get viewings [for other properties],” she said.

“With everything increasing it’s got to the point where I don’t eat as much as I used to, I am afraid to buy food because I am stressed,” she added.

In big cities, the return of some of those who left during the pandemic alongside overseas students and business travellers has led to a spike in demand for rental properties.

Supply and demand have become increasingly mismatched in recent months. According to estate agent Foxtons, there are 40 per cent fewer homes available to rent in London than there were a year ago. According to its data, 28 renters were competing for every new property that hit the market last month.

Meanwhile, landlord groups say the stock of available properties is diminishing because higher taxes and rising interest rates are driving them from the market — though evidence for this is inconclusive.

Ben Beadle, chief executive of the National Residential Landlords Association, blamed higher taxes and other policies for making being a landlord less attractive and shrinking the pool of homes available.

“Rents will only continue to rise unless ministers change course and recognise the damage their policies are causing,” he said.

Official data on the size of the private rented sector is inconclusive. Figures published by the department for levelling-up, housing and communities suggest the number of homes owned by private landlords hit a record level in England last year, while data from the English Housing Survey indicates that the number of households in the private rented sector has actually fallen since 2016.

Neither shows an exodus of landlords, however, suggesting other factors are driving up rents.

The stock of available homes is partly diminished because tenants are signing longer leases. According to Hamptons, half of all leases signed in 2012 were for two years or longer; today that has risen to around three-quarters, meaning properties become available less frequently.

Where possible, tenants want to stay in place to avoid having to find a new home in a competitive market, according to Alicia Kennedy, director of tenant campaign group Generation Rent, which is calling for a rent freeze to protect tenants.

“The real problem is there aren’t enough houses — not enough affordable housing, not enough social houses, not enough housing all together,” she said.

Landlords also face increased costs because of rising mortgage rates and increasingly stringent environmental regulations, some of which are being passed on to tenants.

Elaine Power, a residential landlord in Newcastle, insisted that she could not afford to keep rents down. “There are three parts to this story: tax increases on mortgage interest rates, regulation around energy efficiency and rising interest rates,” she said.

But tenant groups complain that less scrupulous landlords are opportunistically inflating prices and exacerbating a surge in homelessness.

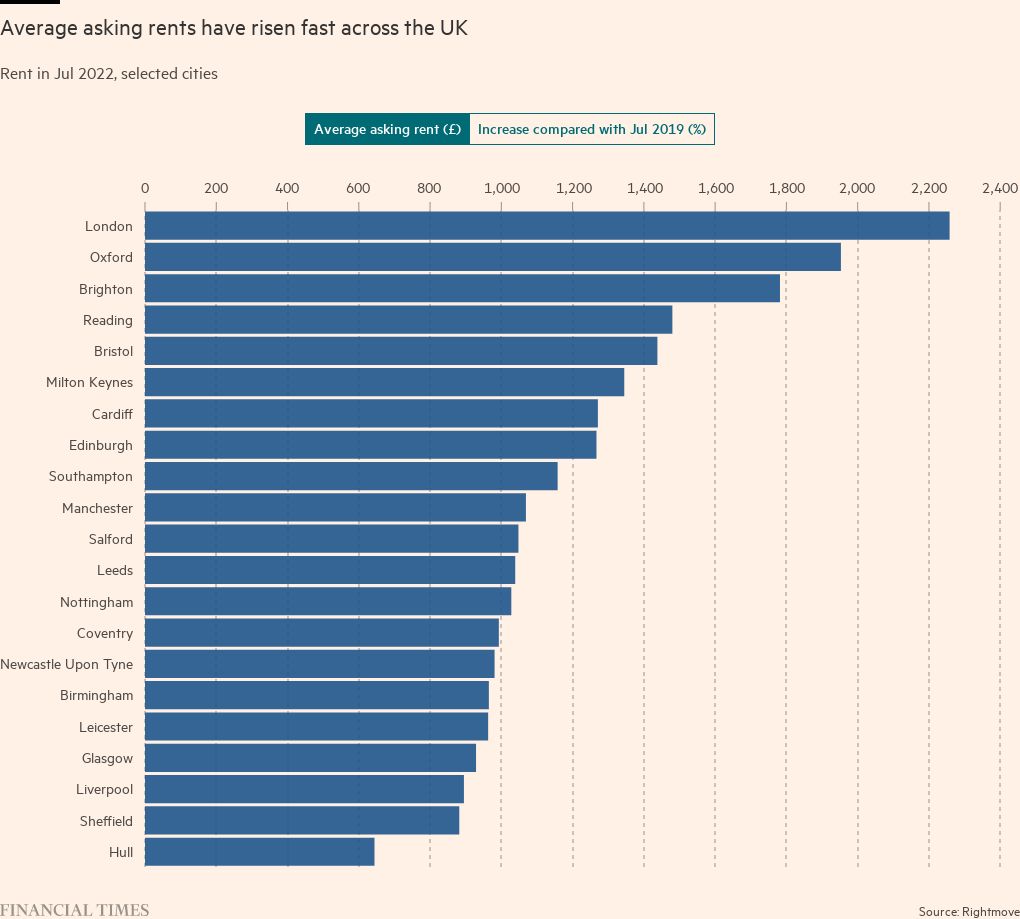

Data from property portal Rightmove suggest landlords are confident they can raise rents far beyond pre-pandemic levels. In London, the average asking rent last month was 14 per cent higher than in July 2019; in Manchester 27 per cent up and in Cardiff 36 per cent higher.

In Manchester, 25-year-old Tilly, who did not want to give her full name, said that after renting together for a year, she and her boyfriend were forced to move out after being served an eviction notice at the end of their tenancy. “All of our stuff is in storage and we are now sofa surfing with friends and family.”

She added there were very few properties available and those comparable to their previous accommodation are now 30 to 70 per cent more expensive. “It’s been horrendous, it’s really affected our mental health,” she said.

According to the government guidance, rent increases “must be fair and realistic, which means in line with average local rents”, but there is no cap on the amount landlords can increase rents on existing tenancies or between tenants.

Meanwhile, average local rents are jumping. Power is renewing the leases on two-bed properties she owns in the east end of Newcastle and has been advised by local estate agents to raise rents from £450 to £600 a month.

Such increases are spilling over from expensive cities into more affordable areas. “People are moving to Scotland because prices are lower,” said Sean Baillie, national committee member at Scottish tenants group Living Rent. “The housing problems in London and Dublin are now spilling over into Glasgow.”

This spillover has stoked concerns that the national rental market is overheating, with potentially dire consequences for tenants. The end of a tenancy is the most common cause of homelessness in England; since a moratorium on evictions was lifted last year, the homeless population has risen sharply.

According to government figures, 13,810 households were at risk of homelessness in the first three months of this year, up 17 per cent on the same period of 2019 and almost double the same period in 2021. The main reason for the increase, according to the government, is “landlords wishing to sell or re-let the property”.

A rise in invisible homelessness is already being seen, said Baillie. “This doesn’t necessarily mean loads more people on the streets, but people sofa surfing or living with friends.”

Are you facing difficulties managing your finances as the cost of living rises? Our consumer editor Claer Barrett and finance educator Tiffany ‘The Budgetnista’ Aliche discussed tips on the best ways to save and budget as prices across the globe increase in our latest IG Live. Watch it here.

Comments