Star power: the strange rebirth of astrology

Angel Eyedealism is a New York institution: a performance artist who has been giving astrological readings for more than 20 years. It is Tuesday afternoon, and I am sitting in the living room of her studio apartment, which smells like incense and is covered in scarves. She’s wearing a long purple robe and pink fuzzy slippers, and I have just paid her $350 in cash to read my birth chart over the course of three-and-a-half hours.

I was lucky Eyedealism could fit me in at short notice, because in recent years her business has exploded — she can barely keep up with bookings. When I visited, she was considering a request from the trendy W Hotel in Times Square to be their in-house astrologer, and she may accept it — but not until Mercury is out of retrograde.

Eyedealism is an old-school practitioner reaping the benefits of a new wave of interest in her art. The ancient practice of astrology, invented by the Babylonians nearly 4,000 years ago, has received a millennial facelift and a massive, tech-enabled boost. For the first time since the 1970s, young people are talking about sun, moon and rising signs in polite company, and market demand seems, well, astronomical (Americans alone are spending upwards of $2.2bn annually on “mystical services”).

Apps have popped up to both feed and meet the demand, the most notable being Co-Star, which has just over 6.5m users, an average user age of 24, and more than $6m in venture funding — all within the past two years. Meme Instagram and Twitter accounts such as @notallgeminis and @trashbag_astrology have appeared, accruing hundreds of thousands of followers each and bringing the language and symbolism of the cosmos to a new crowd. According to the Pew Research Center, about a third of Americans aged 18 to 29 believe in astrology. All this raises an obvious question. It’s 2019. How did an unproven pseudoscience win over a new generation?

Two days before my reading with Eyedealism, I meet Rebecca Gordon in her chic, chandeliered, celestially white SoHo living room. Dressed for a yoga class in all-black athleisure, Gordon is the astrologer I’d send a sceptic to. While Eyedealism does corporate parties, Gordon does corporate retreats. Like Eyedealism, Gordon is profiting from the recent boom, working with companies from Soho House to Chanel, teaching online courses, writing books, doing TV appearances and charging for private readings.

“Social media has given astrologers who actually do the work a natural PR committee,” she tells me with a smile. “These meme people are providing access points for people who wouldn’t normally be into it. I’m all for the democratisation of astrology.”

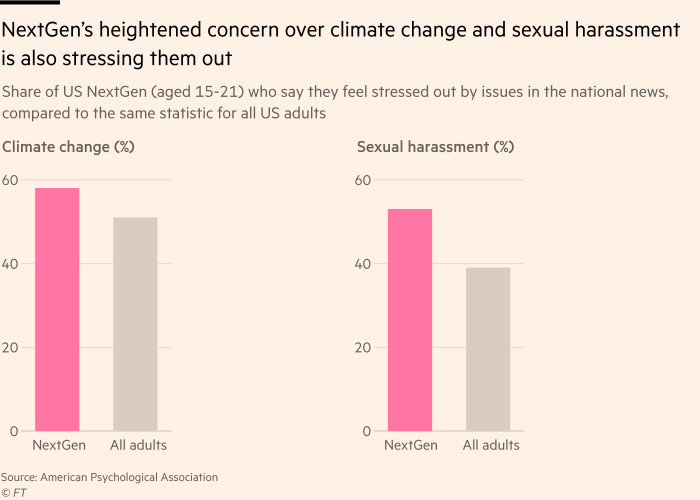

Gordon believes that young people’s attraction to astrology parallels the generational rise in anxiety and technology addiction. According to Deloitte’s 2019 global millennial survey, there has been a marked deterioration of optimism among millennials and Gen Z, and a growth in both macroeconomic and daily anxieties. Sixty per cent of respondents said they’d be happier if they spent less time on social media.

According to Gordon, astrology gives us a connection that humans used to hold more deeply, to the Earth and the sky. “We have lost ritual and rites of passage that all ancient cultures had,” she says. “Like eclipses, solstices, times where you can honour the Earth. As we destroy the Earth and cut off or deny our relationship with the sky, we become more secluded from each other, and disconnected. Astrology reconnects us to the natural cycles that we’ve grown apart from.”

That said, much of today’s astrology lives online and in apps. Co-Star is currently the app to beat, the one growing organically over post-work drinks across the US. Both mystical and modern, it makes much of its use of artificial intelligence and Nasa planetary data, which is fed into a proprietary algorithm. The algorithm then takes pieces of horoscopes written by in-house astrologers and poets (presumably experts in writing viral content), and slices and dices them into personalised updates. There are compatibility reports with friends, and tweetable push notifications (“Try to function without social approval”). It’s minimalist, genderless, slick and of-the-moment. It’s also free, unless you want to test your compatibility with someone who won’t download the app. That costs $2.99 per input and is the only way, so far, that Co-Star makes money.

Co-Star may be leading the charge, but there is fierce competition for the market. Sanctuary, which has raised $1.5m in funding and describes itself as the “Uber for astrological readings”, offers 15-minute monthly texting sessions with an astrologer for $19.99 a month. Vice’s Astro Guide, which charges $5.99 a month, emphasises the fact that its horoscopes are written by experienced astrologers. “There’s so much news in the world every day,” their senior horoscope writer, astrologer Annabel Gat, told me in an unsubtle dig at Co-Star. “I would never want my own horoscope to come out of some prewritten crank.”

All these apps draw on the same fundamental formula: they match where the planets were at the exact time, date and location of your birth to pin down your astrological persona, and overlay them with where the planets are today and in the year ahead to make predictions. It seems almost inevitable that something so ultimately mathematical could be built into an algorithm and pumped through an app. But the product, though popular, is far from perfect.

Co-Star sometimes dishes out striking truths, but at other times reads like a collection of sentences that mean nothing at all. Astro Guide tells me to wear a crisp white shirt to celebrate a professional recognition that never comes. My 15 minutes with Sanctuary’s astrologer is pleasant but extremely vague, more live-chat customer support than a meaningful glimpse into my psyche.

For Banu Guler, chief executive of Co-Star, astrology apps are only secondarily about astrology; they exist instead as an antidote to the toxicity of social media and as a way for people to communicate. “We thought there was this opportunity to make a product based on astrology that actually brought people closer together,” she tells me over the phone. “Every week there’s new research that says there’s a direct correlation between hours spent on Instagram and incidents of teen suicide . . . Everyone’s looking for tools that give them a way to have these conversations.”

Anarghya Vardhana, a partner at Maveron, a venture capital firm that led Co-Star’s $5m seed round, thinks niche, single-purpose platforms such as Co-Star will thrive as social platforms like Facebook and Instagram get unwieldy in size and purpose. I ask her why she invested. “The early growth and engagement were really impressive,” she says, “Even in its early days, Co-Star was quickly becoming the brand around astrology. It’s allowing people to ask the right questions, think about different aspects of life in a more in-depth way, then use those snippets to have deeper and more meaningful conversations.”

Most professional astrologers I spoke to had little patience for the question of whether astrology is real. Enthusiasts describe it as a tool to help people discuss their lives and relationships, and find its scientific credibility entirely besides the point. Here they have something in common with Carl Jung, founder of analytical psychology, who believed that astrology’s correlations to reality were coincidental, but considered it the “psychology of antiquity”, one of the oldest ways of categorising people into timeless archetypes. To him, astrology offered a useful shorthand for us to communicate our tendencies.

The Next Generation

Forget the millennials — a new generation of disruptors is on the move. Explore the series here.

Part one

Reshaping Africa’s future

Part two

NextGen in charts

Part three

The new sound of pop

Part four

How video shaped a generation

Part five

Lunch with the FT

Astrology has experienced revivals before. Not so long ago, almost every newspaper, regardless of quality, would publish a daily horoscope. The tradition was born out of a wildly successful column published in the Sunday Express in 1930, attempting a new angle on the birth of Princess Margaret (RH Naylor, who wrote it, astutely predicted she would lead “an eventful life”). In the 1960s and 1970s, a New Age resurgence of astrological interest ushered us into the “Age of Aquarius”, and even the Playboy Club employed an in-house astrologer. In the mid-1980s, US president Ronald Reagan bolstered it again when it was revealed that he and his wife Nancy consulted a White House astrologer before important events.

Humans have always looked for order in the chaos of daily life, but they may search more urgently at moments of social and political instability. According to the American Psychological Association, 62 per cent of Americans say the current political climate is a source of stress. With governments in flux, a climate crisis sparking international protests, brewing trade wars and rising student debt, it’s no surprise that people are looking for reassurance.

There are other social currents at work, too. According to Pew, 27 per cent of Americans now think of themselves as spiritual but not religious, up 8 per cent in five years. Astrology may be a form of spirituality that works for us now: unlike religion, there’s no moral code or sin, and it can be a convenient way to explain one’s shortcomings — “sorry, but I’m a Scorpio!”. “Astrology takes judgment and blame away,” says John Marchesella, president of the New York chapter of the National Council for Geocosmic Research and an astrologer for 43 years. “It certainly believes in both fate and free will, but it’s bigger than just being screwed up because of what your parents did.”

Marchesella is sceptical about the benefits of online astrology. “There is nothing that can compare with an in-person reading, so long as you’re dealing with a professional. No computer program, no website, no Wikipedia, no googling. Because in person you’re getting more of a counselling experience, a human experience. Along with the information you’re getting some compassion, sympathy and validation.”

Only time will tell if tech can successfully scale up this ancient practice, and whether the current wave of interest will build or subside. For now, you could always ask an astrologer — to them, the answer is likely in the stars.

Additional reporting by Madeleine Pollard

Lilah Raptopoulos is the FT’s US head of audience engagement and co-hosts the FT podcast Culture Call

Follow @FTLifeArts on Twitter to find out about our latest stories first. Listen and subscribe to Culture Call, a transatlantic conversation from the FT, at ft.com/culture-call or on Apple Podcasts

Comments