Property offers ready shelter for criminal wealth

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Pictures of Manni Hussain, with his fat cigar and aviator sunglasses, caught the attention of the British press last month, when the Leeds businessman became the first person to surrender properties to the UK’s National Crime Agency (NCA) because of suspected money laundering.

Mr Hussain handed over flats, houses and offices worth £10m after they were made the subject of an Unexplained Wealth Order (UWO), a relatively new legal tool that the NCA can use to freeze assets it suspects were bought with illicit funds.

Property markets in the UK and the US have become hotspots for money laundering, prompting authorities in both countries to introduce new regulations. But some observers believe that not enough is being done — and that coronavirus may have made the problem worse.

Jerry Walters is managing director of FCS Compliance, which provides training and due diligence services for London’s high-end property market. “When we came out of lockdown [in May] and the housing market came back to life, we were incredibly busy,” says Mr Walters, a former police detective. “And we saw some properties coming to market that gave us concerns.”

With lockdown-mandated travel bans impeding cash smuggling and other illicit activities, some criminals will look to liquidate bricks-and-mortar assets, Mr Walters explains. At the same time, the pandemic makes it easier for such transactions to escape scrutiny.

Know your customer

Since 2007, property agents in the EU have been required to carry out enhanced checks on buyers deemed to be higher risk, such as “politically exposed persons” or anyone with links to criminality. Checks include determining the “ultimate beneficial owners” of any offshore companies or trusts involved in a purchase.

But Mr Walters says the pandemic has made due diligence harder by preventing agents meeting buyers face to face, while economic worries may have tempted some agents to rush through sales.

“Because of remote working, there’s more of a chance for people to behave fraudulently, and there’s less of a chance that fraudulent behaviour is going to be discovered,” agrees Jonah Anderson, a partner at law firm White & Case.

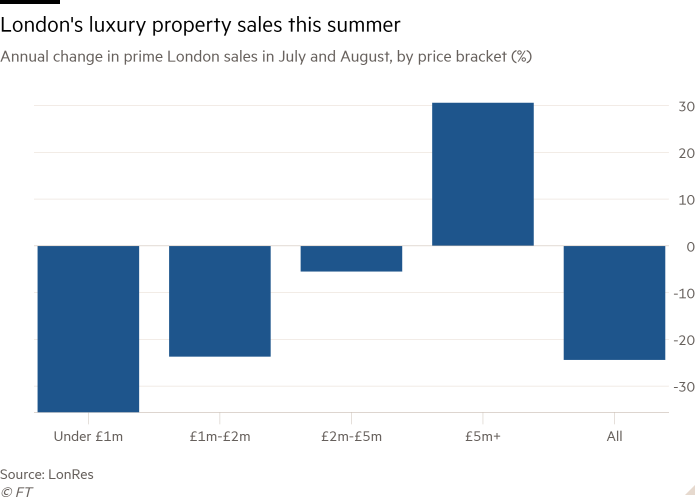

Meanwhile, sales of London’s trophy homes have increased sharply since the property market reopened in May. While the total number of properties sold in the capital’s prime central areas in July and August was down by 24 per cent year-on-year, according to research company LonRes, sales of luxury homes priced above £5m increased by 31 per cent.

Despite estate agents being required to file suspicious activity reports (or SARs) to the NCA if they suspect money laundering, the proportion submitted from the property sector remains stubbornly low. In the 2017-18 tax year, estate agents filed 710 SARs, just 0.15 per cent of the total number submitted. That same year, banks filed 371,522. In 2018-19, while most sectors increased their number of suspicious activity reports, the number coming from estate agents dropped to 635.

“As it stands, it remains far too easy for kleptocrats and criminals to launder their illicit wealth into the UK property market,” says Ben Cowdock, Investigations Lead at Transparency International UK, an anti-corruption pressure group. “Estate agents and solicitors are a first line of defence against this threat but far too often turn a blind eye to suspicious wealth.”

Some argue that a cultural shift needs to take place in the property industry, akin to the one that has been happening at financial institutions over the past decade.

“Nowadays banks will basically end customer relationships if they feel that they can’t be certain as to what the nature is of the business that client is transacting in,” says Mike Hampson, chief executive of Bishopsgate Financial, a consultancy. “And that’s the culture that needs to come through the whole property market.”

Who’s behind the shell?

The US has brought in its own measures to combat money laundering in the property market. They include Geographical Targeting Orders, used by the Treasury’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) in New York, Miami and 10 other metropolitan areas.

Established in 2016, GTOs require title insurance companies — which insure owners and lenders against losses arising from defects in real estate title — to identify the natural persons behind shell companies used in cash purchases of homes above $300,000.

A research paper co-authored by Ville Rantala at the University of Miami and Sean Hundtofte at the New York Federal Reserve found that, after the first GTOs were introduced in New York and Miami, all-cash property purchases by corporations fell by about 70 per cent across the whole of the US.

In the UK, the success of UWOs, introduced by the 2017 Criminal Finances Act, has been patchier. In June, the NCA was hit with a £1.5m legal bill after a failed attempt to impose the orders on three London properties worth a total of £80m owned by Dariga Nazarbayeva and Nurali Aliyev, the daughter and grandson of the former president of Kazakhstan.

Mr Anderson says that, for all the attention UWOs attract, other legal tools may be more useful. “For most practitioners, the jewels in the crown of the Criminal Finances Act are the account freezing and account forfeiture orders, which can be pursued in the magistrate’s court,” he says.

From the time UWO powers came into force in January 2018 to the end of March this year, the NCA had obtained the orders on four cases with an estimated total value of £143.2m (which includes the properties owned by Ms Nazarbayeva and Mr Aliyev, and by Mr Hussain). In the 2019-20 tax year alone, AFOs accounted for the freezing of £208m.

Meanwhile the most comprehensive measure for combating money laundering in the UK remains tantalisingly on the horizon. The Registration of Overseas Entities Bill, which would require all overseas companies that currently own UK property to reveal their ultimate beneficial owners, has been in draft stage since mid-2018, but was mentioned in the Queen’s speech — which sets out the government’s agenda — last December.

Although the coronavirus crisis has reduced the amount of parliamentary time available, Mr Cowdock is optimistic about its prospects for becoming law next year.

“It has cross-parliamentary support: the government wants to introduce it and the opposition parties are in favour of it, so it shouldn’t have any problems passing.”

Comments