Evelyne Axell: pop art’s forgotten star takes the limelight

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Events and event planning are being disrupted by the worldwide spread of coronavirus. For the latest updates, read the FT’s coverage of the outbreak

Evelyne Axell’s life could read rather like a movie plot. Glamorous young actress enlists the help of Magritte to become a successful artist and dies in a tragic car accident. But there’s much more to the picture, as a new exhibition reveals. The Belgian pop artist’s vibrant paintings, collages and plastic sculptural works exploring freedom and femininity are being brought together for a highly anticipated summer retrospective, Body Double, at Polish collector Grażyna Kulczyk’s Muzeum Susch in Switzerland. It is the largest presentation of Axell’s work outside Belgium in decades.

Born in 1935, Evelyne Devaux was brought up in a Catholic family in Namur, the daughter of a silverware craftsman. After a chance meeting on a train, she married the TV documentary director Jean Antoine in 1956; he encouraged her to change her surname to Axell, and cast her in a film the following year. Moving to Paris in 1959, she went on to star in a number of films directed by her husband and André Cavens – alongside writing and starring in the interracial romantic film Le Crocodile en Peluche.

But art, which she had studied for a year, became a way to reclaim her independence, notably from her husband but also from the misogyny inherent within the film industry. In 1964, she asked family friend René Magritte to tutor her. She was the only pupil the artist ever took on, and visited him twice a month for a year. Then, on a trip to London alongside her husband, who was making a documentary about the British pop-art scene, she was introduced to artists including Patrick Caulfield, Joe Tilson, Allen Jones and Pauline Boty. Something clicked, even though pop art, often seen as a male-dominated genre, was something Axell had resisted – much like her contemporaries Niki de Saint Phalle, Marisol Escobar and Yayoi Kusama.

Following comments on her beauty from male art critics, she took the gender-neutral mononym Axell. She was a product of her times: a beautiful woman well aware of the restrictions of patriarchal society, frustrated at the representation of femininity and embracing sexual liberation. “My subject is clear: nudity and femininity experiment in the utopia of a bio-botanical freedom, that means a freedom without frustration or gradual submission, and that tolerates only the limits that it sets itself,” she said in 1970.

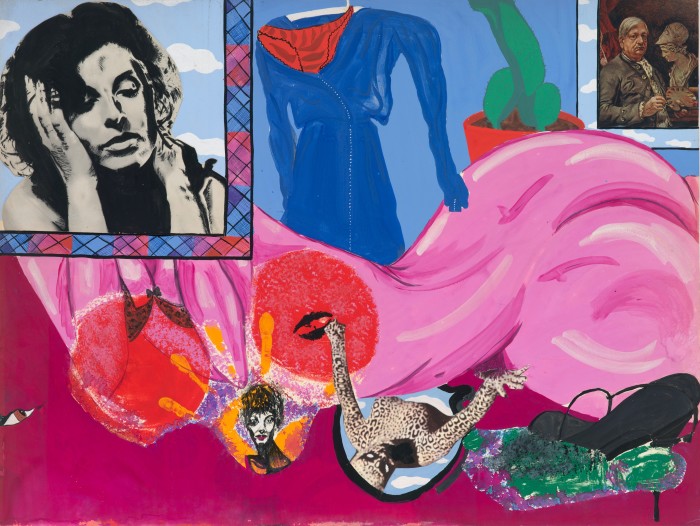

Playfulness in her work is most often a wry commentary on the active and passive woman. Colour and nudity are everywhere. Her 1966 portrait of Soviet cosmonaut Valentina Tereshkova, Valentine (1966), purchased in 2016 by the Tate, depicts a girl in a white space suit and features a zip that peels back to reveal Valentina’s naked body. Her characters are nothing if not sexy. Ice Cream (1964) shows a woman licking a phallic ice-cream cone with joyous abandon. The image was temporarily removed by Facebook censors in 2016 – her work still provokes a reaction.

But Axell’s women are shown to be enjoying their pleasure for their own sake, rather than conforming to the viewer’s desire. In her 1969 ‘happening’ at the Richard Fonke Gallery in Ghent, Axell invited a collector’s wife to enter a gallery nude except for an astronaut’s helmet. In front of a gaping crowd, Axell slowly dressed her, in a reverse striptease.

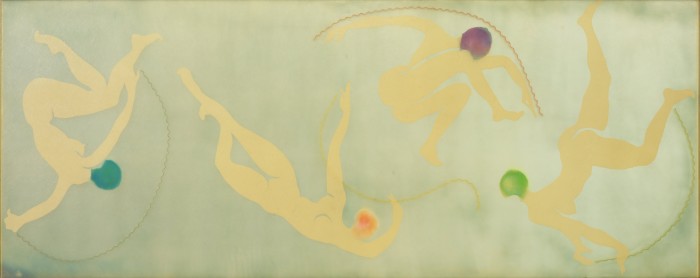

Cars are another ongoing motif: ignition switches, red heels pressing down on the accelerator, a nude woman behind a steering wheel. Drawn to industrial materials like plastic Clartex, Plexiglas and aluminium, Axell cut them into shapes, spray-painted them, created depth out of layers, played with the opaque and transparent nature of the synthetic sheets, and rejected the rigidity of the rectangular canvas. Her works were often round, in the shape of lobsters, or reliefs outlined in a female silhouette.

In 1967, she had her first solo show at Brussels’ Palais des Beaux-Arts and, in 1969, won the Young Belgian Painters Prize. But in 1972, at the age of just 37, Axell was killed in a car accident outside Ghent. At the time, she was looking at representations of male eroticism and the Tarzan myth, planning a show in Mexico and thinking of moving to Guatemala.

For decades, Axell’s work was overlooked, but in recent years, following a readjustment of the gender imbalance in art history, she has been repositioned as one of the most interesting artists emerging from pop. Her work has been included in Manifesta 11, in exhibitions at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis and in the collection of the Centre Pompidou. Some critics have suggested she is the most important pop artist to emerge outside the USA and UK. Axell’s vibrant work exudes pleasure. As the artist pointed out in 1970: “Despite all aggressiveness, my universe abounds above all in an unconditional love for life.”

Evelyne Axell: Body Double runs until 6 December (muzeumsusch.ch)

Comments