Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

This article is an on-site version of our Unhedged newsletter. Sign up here to get the newsletter sent straight to your inbox every weekday

Good morning. All anyone could talk about yesterday was the Federal Reserve. The noise from Washington drowned out a rather alarming European Central Bank meeting. We’ll have more to say on the ECB soon (if you can’t wait, Martin Sandbu has an excellent column). Email us: robert.armstrong@ft.com and ethan.wu@ft.com.

The Fed’s new approach

Monetary policy tightening slows inflation by pulling demand down so that it no longer exceeds supply. How it does this is not subtle. It makes credit more expensive, so companies invest less and consumers spend less. It makes asset prices fall and asset markets less liquid, so companies and households become poorer and less inclined to spend. It makes people not get hired and it makes people get fired. It does this quite indiscriminately. It is not a scalpel, it is a sledgehammer. It smashes things.

For a while, the Fed had been suggesting that it could swing the hammer and get scalpel-like results. As of yesterday it is being more realistic. Here is chair Jay Powell:

Our objective really is to bring inflation down to 2 per cent while the labour market remains strong. What’s becoming more clear is that many factors we don’t control are going to play a very significant role in deciding whether that’s possible . . .

We don’t seek to put people out of work [but] we also think you really cannot have the kind of labour market we want without price stability . . .

The role that we can play is around demand.

With yesterday’s 75 basis point interest rate increase, the Fed is tightening as fast as it thinks it can, even if that means lay-offs. As Capital Economics pointed out, the central bank cut this sentence from its pre-meeting statement (italics ours):

With appropriate firming in the stance of monetary policy, the committee expects inflation to return to its 2 per cent objective and the labour market to remain strong.

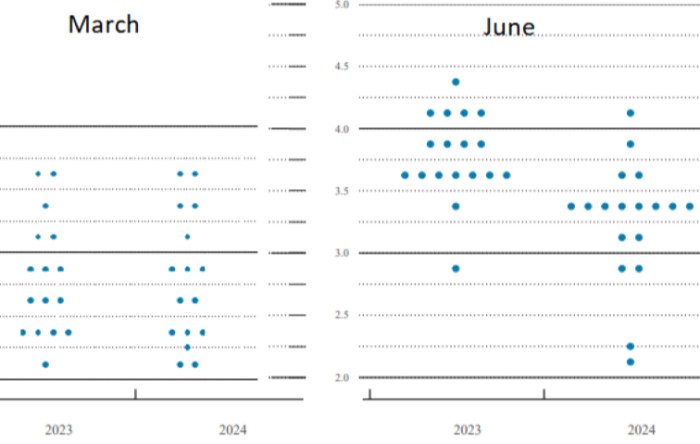

Why the change in stance? As Powell explained at his press conference, preliminary data showing that five-year inflation expectations had ticked up to 3.3 per cent from 3 per cent gave the central bank a kick in the pants. The dot plot, which shows individual Fed committee members’ expectations for interest rates, has moved up a lot. The median dot is now at 3.8 per cent, up a full percentage point since March:

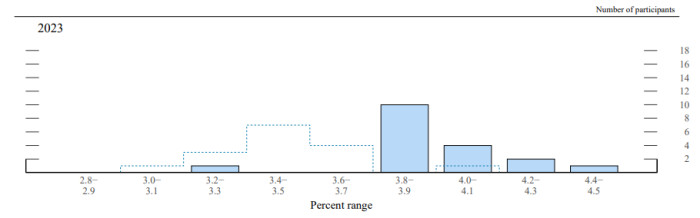

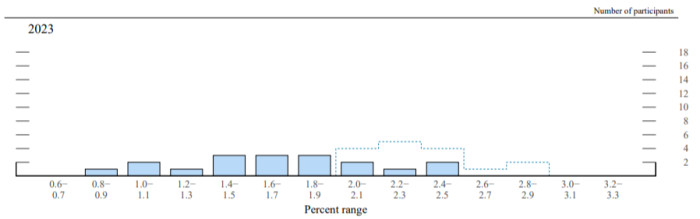

Equally, if not more importantly, the Fed’s estimates of future unemployment and output growth have fallen quickly too, acknowledging the sledgehammer for what it is. Here is the committee’s estimates for 2023 unemployment. The blue bars are the projection from this month, and the dotted lines are from March:

In absolute terms the projections still look rosy. If unemployment peaks at 4 per cent or so next year, that will be a remarkably good outcome. But the point, for purposes of assessing the Fed’s current approach, is not so much the level as the direction and pace of change. It’s a similar story with growth of gross domestic product:

Notably, the words “soft landing” never left Powell’s lips until asked by a reporter if it was still possible. His response:

I do think it’s possible . . . Can we still do it? There’s a much bigger chance now that it’ll depend on factors we don’t control. Spikes in commodity prices could wind up taking that option out of our hands. So we just don’t know.

Because the 75bp increase was telegraphed on Monday, markets didn’t move much in response to the official announcement. What did move markets, though, was when Powell said the next meeting’s rate increase would not necessarily be 75bp but could be 50bp (or something else), depending on the data. Futures markets lopped some 20bp off the terminal rate, stocks rallied and the two-year yield dropped like a rock (chart from CNBC):

Hans Mikkelsen at Wells Fargo thinks markets are fooling themselves again:

Recall that on the day of the prior FOMC meeting (May 4) we saw the same reaction in markets (stocks up 3 per cent) as Fed chair Powell during the press conference stated that a 75bp rate hike was not under consideration. Later — starting May 23 — credit spreads rallied hard for a little more than a week on [Atlanta Fed president Raphael] Bostic’s comments that a pause was possible at the September meeting . . .

In both cases the Fed comments resulted in loss of credibility and created unnecessary volatility in credit spreads in the form of rallies — that would later be at least partially reversed. That just happened again. Fool me once, fool me twice, fool me thrice. We would fade today’s move tighter and think credit spreads need to be materially wider as the Fed continues to be behind the curve.

Fair point that yesterday’s stock market rally was daft. But it’s not a matter of credibility. This week, Powell and the committee demonstrated that they are perfectly willing to change their stance in the face of new data. And Powell reinforced the point, saying the committee is not locked into a series of 75bp increases — a very sensible point to make. Yet the market acted as if he had taken a rate hike off the table. That’s dumb, as Mikkelsen points out. But the Fed being data-dependent in an emergency does not create a credibility problem. (Wu & Armstrong)

Is the Fed’s new approach priced in?

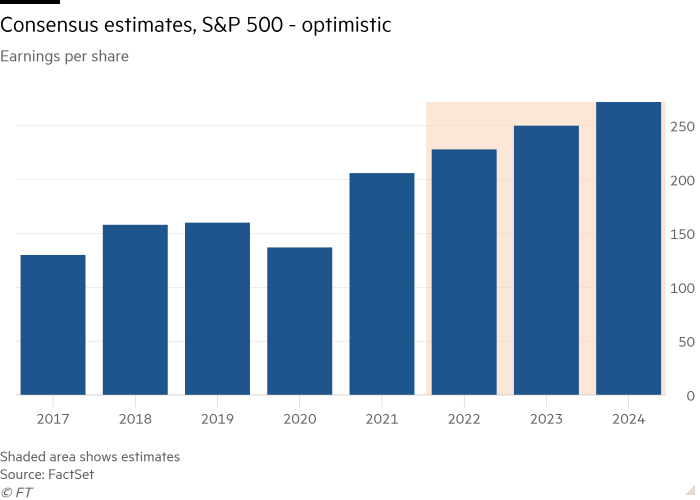

The Treasury market has responded very quickly to the dramatic shift in the Fed’s position. With the S&P 500 down 21 per cent from its peak, you might think that equities had adjusted, too. You’d be wrong, though. Here are consensus estimates for earnings per share for the index:

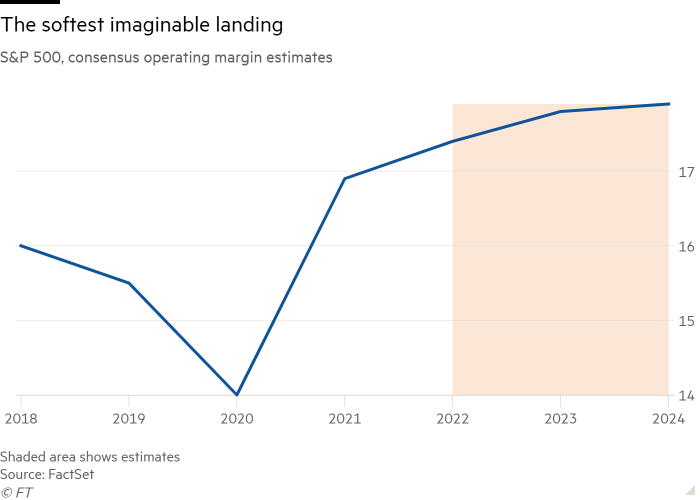

These estimates are all but unchanged from six months ago, according to FactSet. Bottom-up company analysts may believe that recession risks are rising, but somehow, according to their models, the earnings of the companies they cover will not be affected. In the real world, margins are already coming off their peaks. Here’s what’s happening in the analysts’ heads:

It is hard to argue that the market has fully priced in the possibility of recession when consensus estimates are so disconnected from reality.

Price/earnings multiples have come down, but the denominator of the ratio is bonkers. For example: the S&P is now trading at 15.2 times next year’s earnings, down from 19.2 months ago. But suppose earnings fall 10 per cent next year, instead of rising 10 per cent as consensus implausibly expects. Then we are at 18.5 times 2023 earnings. That’s not a great bargain by historical standards. The 10-year average forward year P/E ratio is 16.2.

If you think the Fed is going to push us into a recession, you should also think that the stock market is expensive and has more room to fall.

One good read

I took the CFA as the financial crisis raged, and the testing room was packed. Now we’re in another bear market and it seems no one wants to take the CFA any more. Kids today have gone soft.

Comments