‘Financial monsters’: China’s bad banks complicate property crisis

Simply sign up to the Chinese business & finance myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

To contain the fallout from the Asian financial crisis two decades ago, Beijing set up a group of bad banks and packed them with the country’s most toxic debts. But with deepening distress in China’s property sector threatening to spark wider economic turmoil, those bad banks are now struggling to help.

The problem is that the balance sheets of China’s “Big Four” asset management companies — China Cinda Asset Management, China Huarong Asset Management, China Great Wall Asset Management and China Orient Asset Management — have become so bloated that their capacity is restricted.

The groups are “financial monsters”, said Chen Long, a partner at Beijing-based consultancy Plenum. “I would not count on them to play a big part” in addressing the property crisis,” he added.

While the world’s most indebted developer China Evergrande has taken the spotlight in the country’s spiralling property crisis, stress at the bad banks reveals Beijing’s challenge to mobilise rescue options.

It also underscores the impact of President Xi Jinping’s deleveraging campaign, which has destabilised highly indebted developers, and underscores the risks asset management companies face from a property crisis that they are needed to help ease.

Established in the 1990s, the bad banks expanded far beyond their mandate, becoming financial conglomerates fuelled by debt from investors at home and abroad. Huarong, the biggest bad-debt manager, was bailed out in 2021 after delaying the reveal of a $16bn loss for months.

A debt restructuring is now expected for Great Wall after the company held off releasing its 2021 annual report in June, another signal of weakness across the sector even as its services become more important to the health of the world’s second-largest economy.

Huarong’s problems spooked investors in China’s dollar-bond market in April 2021, prompting ratings downgrades and warnings from global agencies.

Though the trading recovered following the bailout announcement, investors are sensitive about the health of China AMCs. They sold bonds off again in July after Great Wall missed its reporting deadline. Huarong’s 4.25 per cent $37mn perpetual bond fell from 91 to 75 cents on the dollar in July before recovering to about 79 cents in August.

Together, the bad banks have about Rmb5tn ($740bn) in total assets and have resolved Rmb400bn of bad debts in the property market in 2021, one-fifth of the total, according to a Bank of China International estimate.

In the People’s Bank of China’s latest attempt to tame rising discontent over unfinished apartments — including a growing mortgage boycott — central bankers are seeking to mobilise state bank loans from a Rmb200bn funding pool for stalled property developments.

The AMCs have been included in the rescue discussions with central bankers and housing regulators since Evergrande defaulted on its debt last year, according to bank and AMC executives.

Orient and Great Wall raised Rmb10bn bonds each in March to “resolve the risk of quality property projects and rescue the soured debt of the sector”, according to the bond prospectuses.

Cinda stationed one executive on Evergrande’s board and another on its risk resolution committee to help with its restructuring proposal, which is now delayed after missing its self-imposed deadline of July 31. Distressed developers such as Sunac China Holdings and Fantasia Holdings are also actively talking to AMCs about potential rescue plans. City-level bailout funds have also been set up under assistance of AMCs.

But the scale of the funding support from AMCs is expected to be selective and cautious, said David Yin, vice-president and senior credit officer at Moody’s Investors Service, as they already hold large exposure to property developers.

The groups are inextricably linked with the property crisis, said Xiaoxi Zhang, a China financial analyst with Gavekal Dragonomics, a Beijing-based research group.

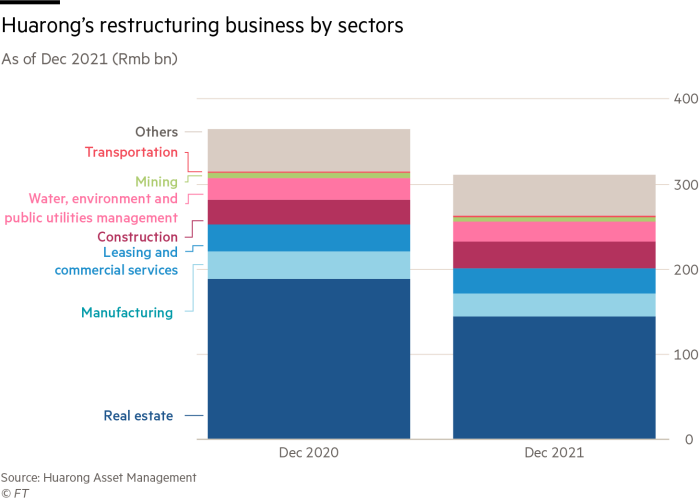

The AMC’s are “substantial creditors” to the property developers, with the sector accounting for between 25 per cent and 42 per cent of total debt assets.

“The ongoing defaults by developers indicate that the effects of the property downturn on financial institutions are still building,” said Zhang in a recent report. “Regulators have pushed the AMCs to reduce their exposure to property, but it remains the single largest sector in their portfolios,” she added.

Huarong and Great Wall are the most exposed to the property sector because of their heavy reliance on debt assets to generate income, in comparison with Cinda and Orient, according to Zhang.

Yet even Cinda issued a profit warning on July 26 that its six-month profit will drop 30 to 35 per cent as “certain financial assets measured at amortised cost held by the company are under greater pressure”. In May, Moody’s downgraded Cinda’s Hong Kong unit, citing “increasing risks arising from the company’s sizeable real estate exposure”.

Smaller AMCs which only operate within Chinese provinces will be expected to carry more responsibility for this round of property sector rescues due to their close ties with local governments, analysts said.

One manager of a smaller regional AMC in Jiangxi, a province in south-east China, said some local asset managers could contribute to the recovery by investing in bonds linked to unfinished housing projects.

He described this as a “fast in and fast out” approach, with an aim for homes to “be delivered in around six months”.

A second option under consideration is for AMCs to form consortiums with new developers or third-party construction groups to take over and restructure the projects, ultimately ousting the current developers. But such deals would be thorny and could take two to three years to complete.

“In general, they are facing challenges of their own,” Yin from Moody’s said about the bad banks. “With capital base capped and lingering pressure on asset qualities, it’s not very realistic for them to invest vastly into the property sector, and as commercial-oriented entities, they’re not strongly motivated to support distressed property projects in lower-tier cities.”

Comments