Miami’s ICA showcases Judy Chicago’s flamboyant feminist visions

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

“I think I’ve heard of Judy Chicago,” mused a young woman to her friend, who looked equally uncertain, as we rode the lift up to Chicago’s solo show at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Miami.

The flag-bearer of feminist art may not currently be a household name but by this time next year she should have another taste of the fame she enjoyed in the late 1970s when she shot to global attention as the creator of “The Dinner Party” (1974-79).

Comprising 39 place settings, each one devoted to a significant female figure, and many evoking vulvar forms, “The Dinner Party” caused a storm of controversy. (One critic described it as “an outrageous libel on the female imagination.”)

Shown from 1979, “The Dinner Party” toured the world but struggled to find a permanent home. Only in 2007 did it settle at the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art at the Brooklyn Museum, New York.

Chicago too has struggled to find solid ground. In 2011 she told the LA Times that she was a victim of “covert censorship, where the only work of mine allowed to see the light of day in terms of real visibility is ‘The Dinner Party’.”

But the profitable winds of fortune that have blown older women artists on to the market’s radar have touched her, too. In 2013, she was featured in Frieze Masters’ Spotlight section for neglected 20th-century artists. Next autumn, she is due to show at Jeffrey Deitch’s Los Angeles gallery, while a show of new work is also planned for Washington’s National Museum of Women in the Arts. If the ICA show is anything to go by, the 79-year-old practitioner deserves the attention.

Entitled Judy Chicago: A Reckoning, the Miami exhibition spans 30 years from the mid-1960s onwards. There’s no explanation of why we are denied more recent work and its absence leaves you hungry to find out what came next. Nevertheless, Chicago is revealed as a twisty, inventive, unpredictable operator with a penchant for silky-smooth, flawless surfaces that are intriguingly at odds with the turbulent anger beneath.

That Chicago was a minimalist in her youth is often forgotten. It’s a joy, then, to see two of her early hymns to a less-is-more aesthetic, “Trinity” (1965) and “Sunset Squares” (1965/2018). The first is a row of three plywood triangles in descending order of size; the second comprises an encounter between four irregularly sized empty squares. In flame-bright scarlet and tangerine for the trio and ice-cream pastels for the quartet of frames, these works herald Chicago’s way with pure forms, sonorous colours, spare lines and empty space. (The distance between each element is calibrated perfectly to maximise their material presence.).

Yet even as she made these voiceless geometries, Chicago was exploring fiercer, more flamboyant narratives. Spray-painted on car bonnets, “Flight Hood”, “Bigamy Hood” and “Birth Hood” (1965-2011) see her arrange body parts — vulva, phallus, buttocks — into immaculate, abstract symmetries in a gesture that wrests control of the erotic body back from centuries of male artists.

By the 1970s, Chicago was immersed in feminism as an artist and teacher at the California Institute for the Arts. For those of us who are rarely west of the Atlantic, the chance to see test plates for the iconic “Dinner Party” is not to be missed. With thick, soft, bone-pale folds undulating around an unmistakably labial centre, the bare essentialism of the plate that Chicago dedicated to painter Georgia O’Keeffe makes it if anything more powerful in its unglazed state — as we see it here — than in its final colour version.

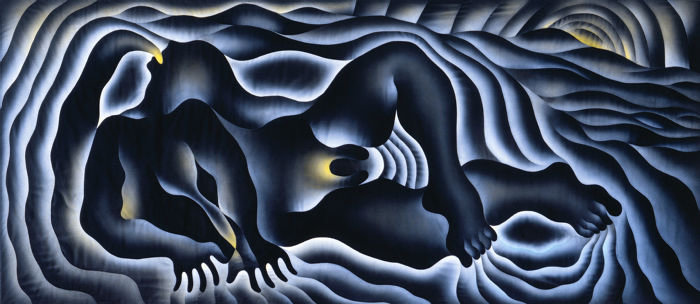

Chicago loved the process of collaboration with other artists and artisans, and unlike many artists she credits her collaborators by name. Perhaps the finest work here is her series “Birth Project” (1980-85), which embraces macramé, quilting and needlepoint. A feminist creation myth lent rare energy through the use of the fabric, the sequence is peopled by fluid, archetypal goddesses who float in the centre of rippling, iridescent contours as if paradise was a Utopian womb.

These ideals of benign, transcendent female authority are in stark contrast to the male protagonists of her triptych “PowerPlay” (1982-87), in which Chicago sprays a mixture of acrylic and oil on to linen to produce shiny, lucid, comic-book graphics that depict muscle-taut male figures despoiling the world.

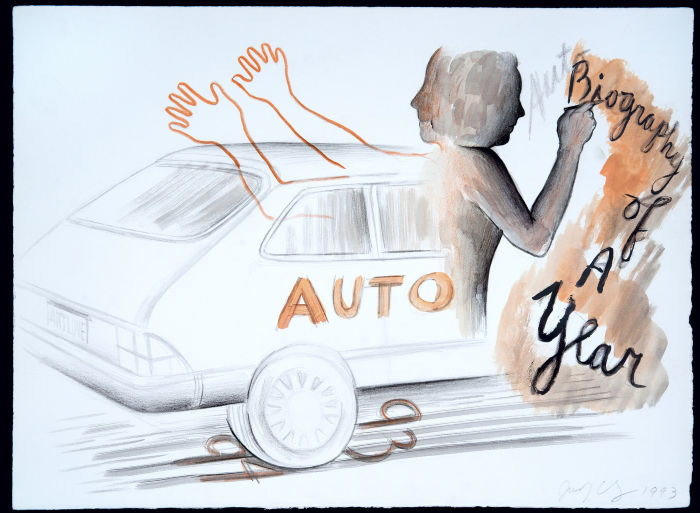

The show ends with “Autobiography of a Year” (1993-94), a series of 140 drawings. This visual journal features sketches of female figures, often near androgyne in their simian solidity, alongside scrawled messages such as “What is the colour of desperate?” and “Betrayed Again”. Yet Chicago’s deft draftsmanship saves her confessionalism from mawkishness. My favourite was a scratchy self-portrait alongside the phrase “Weeping with joy at having a brush”.

Those words — alongside the meticulous quality of her practice — underscore the fact that Chicago was an artist first and a feminist second. Little wonder her work has endured so well.

To April 21, icamiami.org

Comments