Alex Katz: the ‘artist of the immediate’ on why his time is now

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

“Painting is going very well. And outside of that, it’s all pretty crappy,” says Alex Katz, over the phone from New York. The indefatigable 93-year-old artist has just released a new book with Rizzoli, another monograph. This one is larger and fuller than previous publications – there are more than 250 paintings, alongside photographs, sketches and ephemera; works by other artists, which give insight into Katz’s process and ethos; and an enjoyably thorough essay by the art critic Carter Ratcliff.

The book is square and enormous. This heft suits Katz’s current mood as he focuses – sometimes angrily, sometimes humorously – on declaring that he is a brilliant painter who has been underappreciated and largely misunderstood. It’s true that Katz, while popular in Europe – “people wait outside my hotel for autographs” – and liked by the young, is not so adored in his home city of New York, where he has not had a major survey exhibition since the Whitney Museum retrospective in 1986 (although the Guggenheim recently announced plans to hold one in 2022). He is, unlike Cy Twombly or Jasper Johns, not considered a major artist in the way he would like, even though he is, by his own admission, “more popular now than I ever was”. While he is happy with this book – “it’s the one to beat” – he is not happy in general. “I’ll never be happy. I’m not sure what I’m doing. And I dislike most of the New York museums – I don’t think they have taken me seriously.”

“Do you see yourself as an over-the-hill minor talent?” someone asked him a few years ago, during a trip to Spain. “I don’t, but a lot of other people do,” he says. This “conflict” with the institutions gets him down.

At the start of the pandemic, Katz spent three months in Pennsylvania, then three in Maine, where he has a house and where he studied, in the summer of 1949, at the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture. He is now back in the city, trying to avoid people, partly due to the pandemic and partly because he is picky about who he gives the time of day. “Any person on the planet can be interesting for five minutes. A lot of people are not interesting for 20 minutes. If you have dinner with a person, they have to be interesting for a couple of hours.”

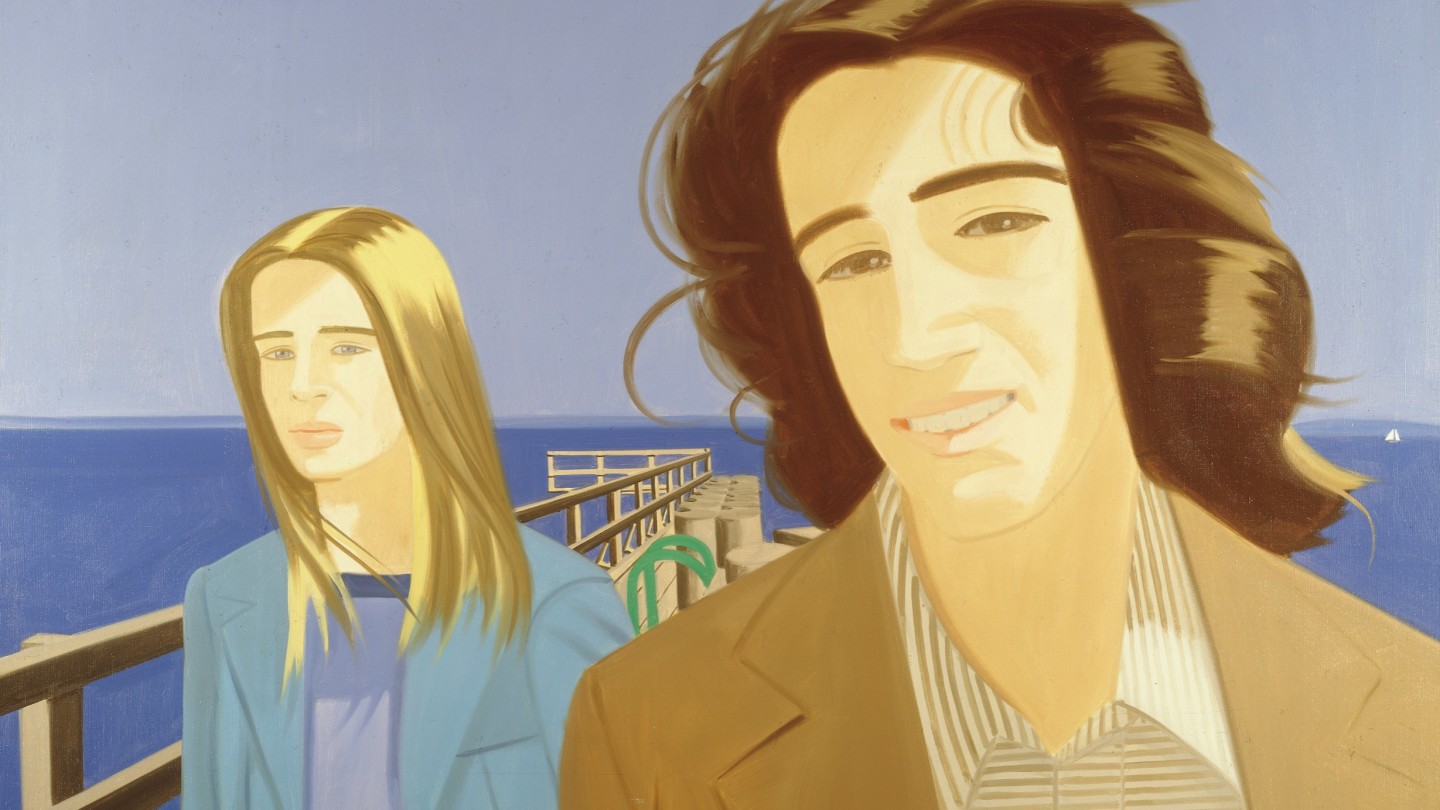

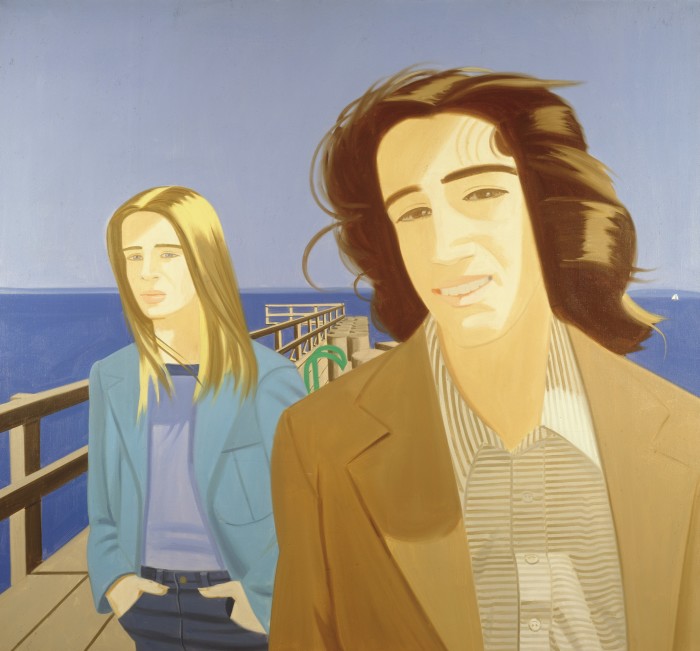

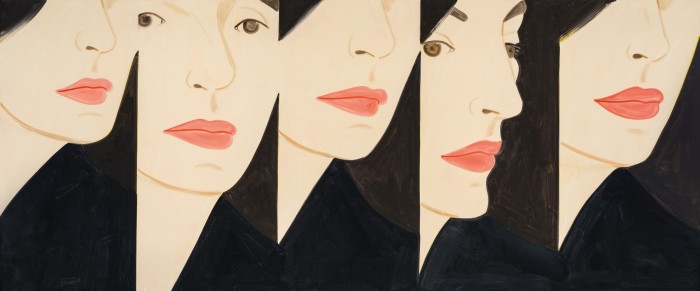

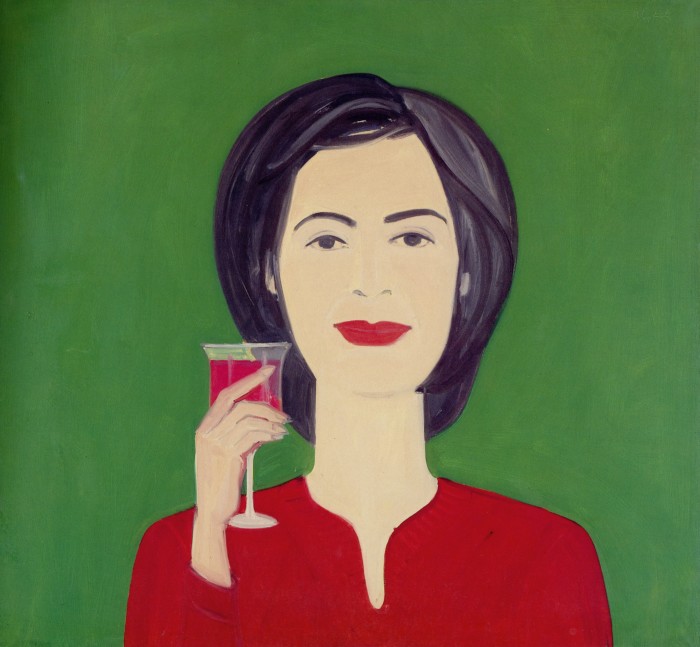

In the book, there are paintings of his circle of smart, creative friends, which has included the writers Kenneth Koch and Frank O’Hara, painter Fairfield Porter and dancers/choreographers Yvonne Rainer and Paul Taylor. There are triumphant blooming flowers and buildings and landscapes. And, of course, there is Ada, his wife, now 92, who he met in 1957, who he has painted hundreds of times and who is the subject of some of his best, and best-known, works.

New York is going to be “a depressed place for a while”, he says. “The people eating in the streets are all kind of disgusting-looking. Bridge and Tunnel has taken over SoHo.” Can anyone be elegant during a pandemic? “I think so. Style never disappears, and neither does good taste.”

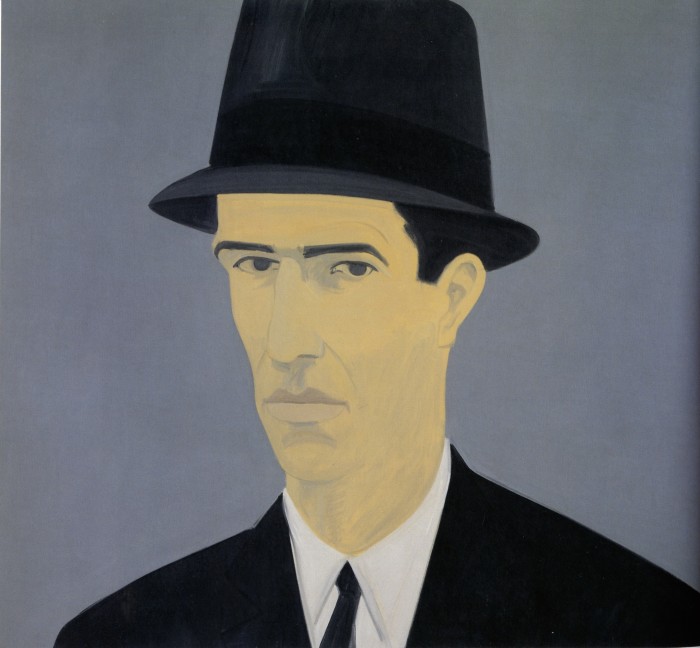

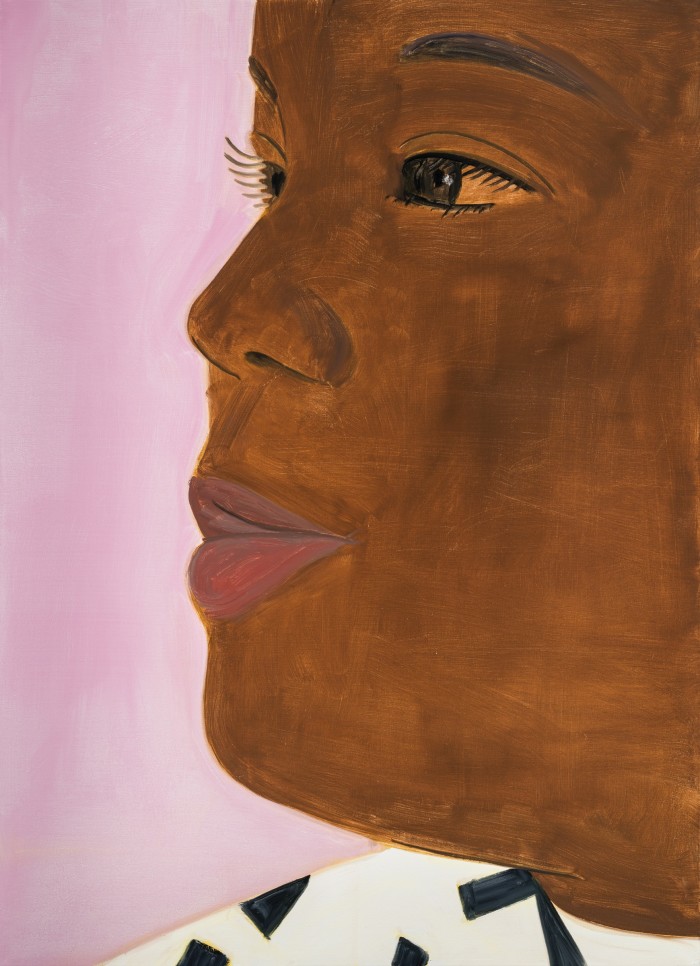

Style and taste are key to Katz – in a subject, he looks at the lipstick, the handbag, the haircut. The smile. The neat black dress. The “artefacts of the culture”, as he puts it. Despite his grumblings, Katz does, in fact, know exactly what he is doing. With each painting he works to capture “the sensation of seeing things for the first time”.

In the book, Ratcliff calls Katz “an artist of the immediate”. Which is exactly right, Katz says. As much as people like to project all kinds of meaning onto his works, they are, he says, about the “immediate present” – not about politics or capitalism or commerce or Trump, but the brief, heavenly, ignorant moment when you look at something, glance without thinking, and just see. His paintings try to capture the flash of light, the visuals that strike the eye right then. The sensation of regarding someone across a room or on the street and seeing the mouth, the eyes, before recognising them – as your ex, your colleague, that girl from the movie. Or perhaps it’s like the emptiness of your head in the morning when you first wake up, before any memories set in. The moment when “you don’t understand the particulars, the details”, as Katz puts it.

You could say something so surface-based was shallow, as some critics have. But Katz feels his works are justified because of skill, “the craft”, the way he makes paint sing. “I felt that [Franz] Kline and [Willem] de Kooning both painted in the now,” he says. “The impressionists were cumulative, they were not in the now.” He likes art that is “trying to get in the present tense”.

That said, Katz believes his paintings are “fairly complicated. At different times they have different publics, and that’s the reason they are still around.” Some people, usually other artists, see the skill of his brushwork, the cleverness of the depth and his ability to capture light. Others, he says, see the subject matter, “the malleability of the images”. And then, “museums see things they can use to show to people. Dealers, something else.” According to Katz, any good painter has to offer these many things at once. “Very few painters hit them all and hold it for any length of time.”

Katz is not remotely interested in the notion of the artist as activist. “We are in a time of hysterical ‘diversity’, is what they call it,” he says. Social art, as he refers to it, was big when he was in art school, and he is “very hostile to it. Social art to me is especially sentimental – you are telling people what to think. I’m doing stuff with flowers. That’s very abstract, it’s just the opposite. It’s got nothing to do with making society better.”

While out of step with the vogue for culture as campaigning, Katz believes his paintings are currently bang on the money. “They never were before.” They stand up right now, he says, in a way that other works don’t. “When you go to a museum, you see the pop artists fading. They don’t hook up with the culture today at all. We’re in the pandemic. It’s no time for cleverness.” By contrast, his paintings “are serious and upbeat and escapist. But they are not ironic and they are not clever.”

Why would one want to be on the money of the now – these strange, dystopian times, with the crumbling faith in politicians and institutions, the looming climate crisis, the inequality? Does he like the present? The question bounces off, like light. “I always like seeing the sun, the air in the morning. It’s the same as when I was 16. It hasn’t changed much.”

“The world is definitely more visual now than it’s ever been,” Katz says. He’s not sure if that’s a good thing, but rather that “there is no progress”. That sounds nihilistic. “Perhaps, but it seems to be going that way.”

The writer Ann Beattie – who published a book on Katz’s work in 1987, positioning 26 of his paintings alongside text that tried to probe their psychological dimension – wrote that “it is difficult to look at some of Katz’s paintings and not imagine there must have been times when his powers of observation pained him.” Later, Katz admitted some of her analysis was true. Beattie notes Katz’s work often seems to show “people failing to connect”. Could there be a more apt description of the modern condition than a mass general failure to connect? A separateness, a loneliness, a rumbling anxiety despite all the technology.

This is also Katz’s personal condition. He is, he says, never sure if people understand him. The new book is surprising in that it puts a focus on his biography – his Russian Jewish parents, his life as a first-generation immigrant child, his schoolboy hobbies. It seems odd to give weight to such things, when he’s been firm that his work is about the paint, the style, the technique – not some urgent inner truth, some story, something he’s bursting to say.

But, if he’s honest, he can draw a thread back to his childhood. When he was a boy, in Queens, he never felt at ease. There was just one other Jewish family living nearby. Though his parents tried to assimilate, they were dissimilar; the only ones with paintings in the house, they were “privately snobs, so we never became friends with the other Jewish family”. He was surrounded by difference, by other cultures. “I grew up in a neighbourhood with 24 houses. All were brand new, and the only thing people had in common was the price of the house. It made me uncomfortable – I felt everybody was better at everything than me. I guess that had a lot to do with my ambition and aggression.”

Feeling separate is usually good for creativity, I offer. And ego; ego is important to good work, and conviction. “Ego’s a big deal,” he says. “The ‘I’m right and you’re wrong’. Your energy impulse has to do with not feeling good. Like when you’re a teenager, you don’t feel good about yourself a lot of the time.” Teenagers, notoriously misunderstood, are unique in the strength of their faith in their hopes and dreams and passions. Feeling underappreciated or overlooked can motivate. “People have always been hostile to me. I think hostility is a big factor in staying alive as an artist.”

If he’s still in a teenage state, he must feel young, I suggest. “I don’t know what young is.” He pauses. “I feel power when I paint, more than I did when I was young. I can watch my body decline, but when I paint I feel power. My father told me, ‘One day you’ll wake up and you’ll feel power all over you’, and I guess that happened. But the uncertainty stayed.”

Alex Katz, edited by Vincent Katz with an essay by Carter Ratcliff, is published by Rizzoli priced at £115

Comments