China fails to stem bond outflows as property woes persist

Simply sign up to the Chinese business & finance myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Michael Li, a China-focused high-yield bond fund manager based in Hong Kong (who prefers not to speak under his real name), is struggling to attract new investment even though he has outperformed the market by a big margin.

“My portfolio is down 12 per cent, while the benchmark is down 40 per cent,” says Li, comparing his year-to-date performance with an index that tracks hundreds of dollar bonds issued by Chinese companies. “How can I tell my client, ‘Do you want to buy a fund that loses money a little bit less than the others?’ I have no story to tell.”

This downturn follows a slump in China’s offshore property bonds, which make up the bulk of the country’s once-lucrative dollar-denominated high-yield debt. They suffered as Beijing’s crackdown on property speculation in the second half of last year prompted dozens of local developers to default on interest and principal payments.

The divergence between a hawkish US Federal Reserve, which has hiked interest rates five times this year, and a dovish People’s Bank of China that is under pressure to relax monetary policy to rescue the sluggish economy, has dealt a further blow to Li’s performance. Investors have raced to ditch Chinese bonds in exchange for better-yielding assets in the world’s largest economy.

Many international bond investors are reassessing their whole China strategy in the wake of the country’s uncertain outlook, which is being weighed down by Beijing’s zero-Covid policy and intervention in the private sector.

“Chinese bonds are certainly investable,” says Satya Patel, head of fixed income at Matthews Asia in San Francisco. “They’re just much less attractive than they were even at the beginning of 2022.”

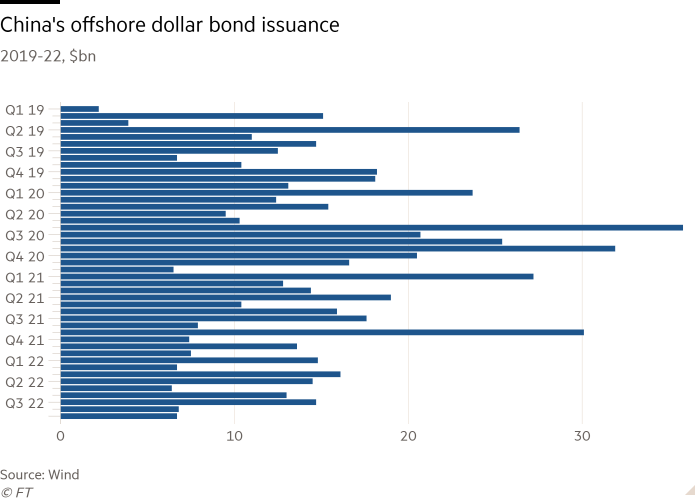

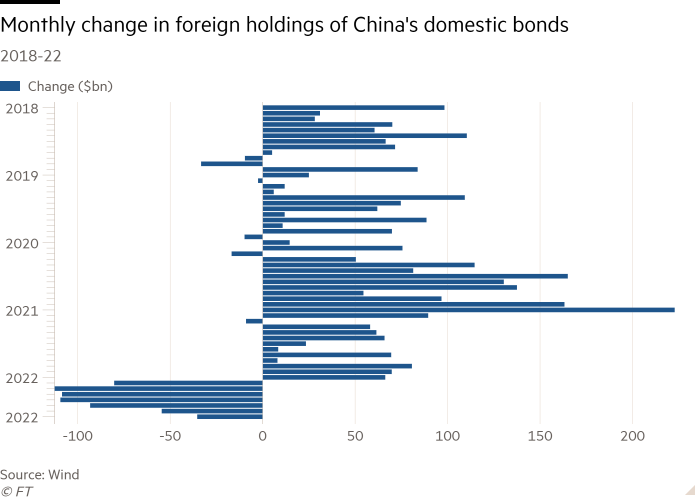

Public records show issuance of China’s offshore dollar bonds — those issued by local businesses in Hong Kong — fell by more than a third in the first nine months of 2022 compared with a year earlier. The picture is similarly bleak in the onshore market — for renminbi-based debt issued in Shanghai — as international investors have cut holdings in China’s interbank bond market for a straight seven months since February.

Mark Baker, Hong Kong-based head of fixed income at Abrdn, estimates China’s domestic debt market has recorded an outflow of about $80bn since the beginning of this year, reversing a “significant” proportion of inflows from previous years.

More than two-thirds of the dollar bonds issued by Chinese developers are trading below 70 cents on the dollar as Beijing cut lending to developers and put restrictions on home purchases, causing a spike in defaults. That suggests investors have priced in more than $130bn in losses from holding these debt instruments.

More from this report

The central government has unveiled a slew of new measures — from cutting mortgage rates to easing purchase restrictions — in a bid to rescue the property industry, which accounts for a third of China’s economic output. But its efforts have fallen far short of investors’ aspirations.

“That did shake confidence in the market and that confidence is not close to returning,” says Baker.

Patel of Matthews Asia, which holds Chinese offshore property bonds, shares this view. “The key thing we’ve learnt over the past 16 months is that the Chinese government is not going to step up and give developers the liquidity [they seek]”, he says. “Investors are also not going to step up and . . . plug the gap.”

According to Morningstar, the five largest Asian high-yield bond funds trimmed their holdings in Chinese developers to 16.4 per cent in June from 27.6 per cent last December.

A weakening Chinese currency, which has lost 11 per cent against the US dollar since the beginning of this year, has added another layer of uncertainty to western buyers of onshore bonds.

“Foreign investors are taking currency risks and they’re at risk of losing all the yields they earn in their Chinese government bonds just because of currency depreciation,” says Patel.

But, in spite of the bleak mood, most international investors still see Chinese bonds as an indispensable part of their portfolio. Baker says buying renminbi-denominated onshore debt could help diversify his portfolio thanks to the low correlation between Chinese bonds and western bonds. “When global markets are selling off, China can still be relatively stable,” he says.

However, the unique nature of the Chinese market — characterised by the heavy state intervention responsible for much of the real estate turmoil — has also made investors wary of risks that traditional models cannot predict.

“The decoupling of Chinese bonds from the rest of the world could make them riskier in the long run,” warns Bo Zhuang, a Singapore-based sovereign analyst at Loomis Sayles.

Comments