London Art Week 2019 — a timely reminder of the value of art dealers

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

London Art Week Winter is a timely reminder of the value of art dealers. As the focus of the powerful auction-houses narrows and their offer becomes ever more homogenous, it is increasingly left to private galleries to flourish the unexpected and overlooked. For the business of the best kind of dealer depends on a good eye and a lifetime’s experience to filter a morass of material to find quality and interest in the unfamiliar or unfashionable, as well as to source — if finances allow — the obvious blue-chip. They are offering their verve and taste as well as their expertise. Without them, the art market would be a far duller place.

For this year’s event in Mayfair and St James’s, 35 specialist dealers combine forces with Sotheby’s, Christie’s and Bonhams auction houses. What is interesting is not so much the something-for-everyone diversity of the material presented — there is anything from antiquities and medieval art to Old and Modern Masters, plus fine and applied arts — but the revelatory nature of the shows themselves.

S. Franses Ltd, for instance, impressive and scholarly dealers of tapestries and carpets, casts light on how the discoveries of the New World transformed the European aesthetic. The age of exploration and discovery introduced spectacular exotic fauna and flora into 16th-century Europe — not only the famous rhinoceros immortalised by Dürer, and the likes of parrots and turkeys — but giant-leaf plants such as gunnera, banana and rhubarb, recorded and engraved in a flurry of botanical books. Suddenly the gentle fields of flowers found in medieval tapestries, the millefleurs with their prancing unicorns, gave way to evocations of the vast primeval forests and jungles of Asia and the Americas.

Their turbulent mass of monumental leaves set against black backgrounds conveyed the wildness and beauty of this environment, and hinted at its danger as well as the natural resources from which pioneers and their royal or noble sponsors could hope to benefit. Although no complete sets survive, these “forest work” or verdure tapestries are known to have lined entire rooms, creating an environment that would now be described as immersive. There is no narrative or symbolism, just the sensation of being surrounded by leaves, birds and butterflies set in motion by flickering candlelight and the viewer’s eye as it is compelled across the pictorial plane.

“It is a very modern concept and aesthetic,” explains Simon Franses.

Some seven museum-worthy rarities of 1500-1560, mostly woven in the Southern Netherlands, are on display, including a wainscot tapestry with a border of pomegranates that may have belonged to Elizabeth I, and a unique piece featuring stag and hounds. Prices £20,000 for a small fragment, to £450,000.

A niche that has been relatively unexplored in the English-speaking world but which has begun to gain increasing market attention is the art of late medieval and early renaissance Spain. Sam Fogg, the pre-eminent specialist in European medieval art, joins forces with leading Madrid Old Master dealer Galeria Caylus to present Retablos: Spanish Paintings from the 14th to 16th centuries.

By the late Middle Ages, the altarpieces of the Hispanic kingdoms had evolved to take a unique form with vast and elaborate frames containing painted panels and sculpture covering the entire east wall of the church. Unlike their Netherlandish and Italian counterparts, Spanish artists remained true to the Gothic tradition, with panels painted as if they were large-scale illuminated manuscripts. Perspective was of little interest; spectacular colour and lavish use of variously worked gold were paramount. Of the 20 panels here, many are previously unpublished or little known.

“This material is very rare but it is still possible to find museum-quality — and often huge — Spanish works in wonderful condition on the international market, and for reasonable sums of money,” explains Matthew Reeves of Sam Fogg. The exhibition, with a catalogue by Dr Aberto Velasco Gonzalez incorporating new archival research, travels to Madrid in the spring. Prices £25,000-£500,000.

Scholarship tends to sideline artists who fall between two national schools of art. Ben Elwes features the Anglo-Americans. Alongside a Benjamin West portrait of a demure Queen Charlotte (1776-77), one of the few outside the royal collection ($850,000), hangs a rather more transgressive portrait recently identified as Mary Robinson, the first mistress of her son, the future George IV. Catalogued in the past as French or English School, it now appears to be a portrait by the Boston artist John Singleton Copley of Robinson, a remarkable actress, writer, feminist and early “It girl”, dressed up as a nun. The frisson comes from the combination of Catholic habit and come-hither look, and the precise placing of her Crucifix on her lap.

Also on offer is a Thomas Moran watercolour of a sublime Utah canyon that originally belonged to John Ruskin ($500,000).

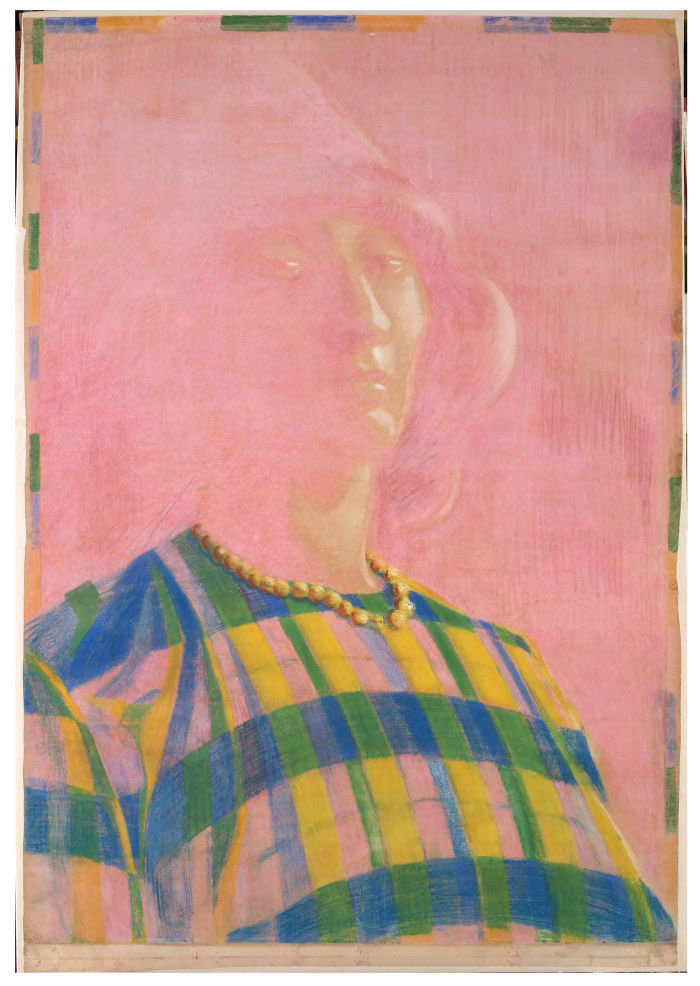

More unfamiliar material is offered by Laocoon Gallery, a new Italian arrival on the London scene. “XX: The Female Gender in Twentieth-Century Italian Art” examines women in any number of guises — and in a wide variety of media, including bronze, terracotta and ceramic — during this period of unprecedented, if sometimes slow, social change. It is salutary to note the date — 1940 — of Pietro Gaudenzi’s monumental, near-monochrome pastel of the silent, slow-moving and imperturbable peasant women of Anticoli Corrado near Rome in their long black dresses and shawls bearing enormous trays of bread on their heads in age-old custom.

Back in 1903, we find the bold and independent self-taught artist Adriana Bisi Fabbri looking defiant in a 15th-century artist’s cap — a man’s cap, of course — her features a shimmering evanescent yellow emerging from the pink ground as if in silverpoint. Prices £5,000-£90,000.

Raccanello Leprince unveils “Orientalisimo Fiorentino”. This small show sets the orientalist production of the 19th-century Florentine ceramics factory of Ulisse Cantagalli in context, and in light of his friendship with the English potter William De Morgan. There is more work from the Cantagalli factory on show at Callisto Fine Arts, too, while in a different genre L’Empreinte, Olivier Malingue’s thematic exhibition, considers how the act and imagery of the imprint has impacted on modern and contemporary art.

The prize for the most unlikely discovery must go to Bagshawe Fine Art for unearthing in Italy a Pre-Raphaelite painting by the obscure and tragically shortlived Adolphus Madot (c1833-1861). His wonderfully observed Shakespearean scene of “Slender’s Wooing of Ann Page” from The Merry Wives of Windsor was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1857 where it was acquired by the future prime minister Lord Gladstone (£55,000).

Most peculiar is the work of the first speaker of the Newfoundland House of Assembly, John Bingley Garland, on show at Lowell Libson & Jonny Yarker. His collages of carefully selected prints and handwritten passages of scripture are covered with cascading droplets of bright red blood — a strange outpouring of Victorian visionary art.

Finally, for those who might be in search of a truly blue-chip work, The Weiss Gallery exhibition of Sir Anthony Van Dyck and his legacy flourishes the master’s fresh and freely painted portrait of around 1637 of Mary Barber, later Lady Jermyn.

December 1-6, londonartweek.co.uk

Follow @FTLifeArts on Twitter to find out about our latest stories first. Listen and subscribe to Culture Call, a transatlantic conversation from the FT, at ft.com/culture-call or on Apple Podcasts

Comments