The onetime Parisian street fighter who gave his company purpose

Simply sign up to the Work & Careers myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

The earliest lessons Pascal Soriot learnt were not about leadership, but loyalty.

Growing up in the Parisian banlieues, Mr Soriot, now chief executive of Anglo-Swedish pharma group AstraZeneca, was not above resorting to fisticuffs as he and his friends defended themselves against rival groups of neighbourhood teenagers.

“[It’s] nothing that I’m very proud of, but when you’re in an environment like this it creates a sudden realisation that you have to stand up for yourself, you have to stand up for the team,” he says.

That sense of esprit de corps, enhanced by a shared threat, was to loom large again many decades later when Mr Soriot, 60, now a picture of good-humoured suavity, found himself in the fight of his life against an American multinational in the shape of Pfizer, which was bidding to snap up Astra .

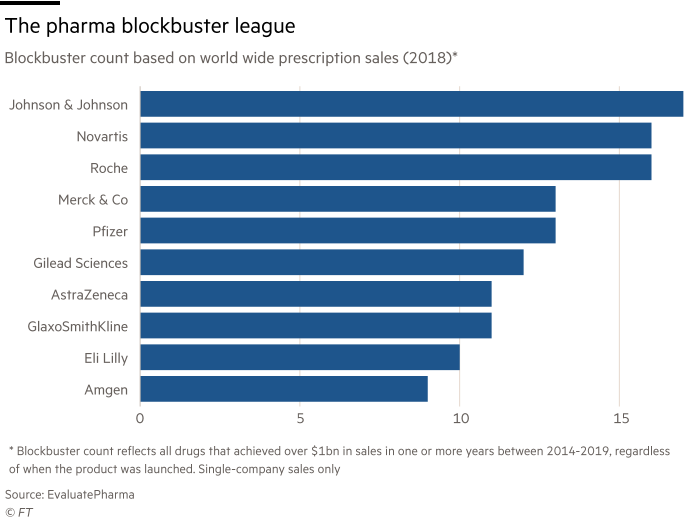

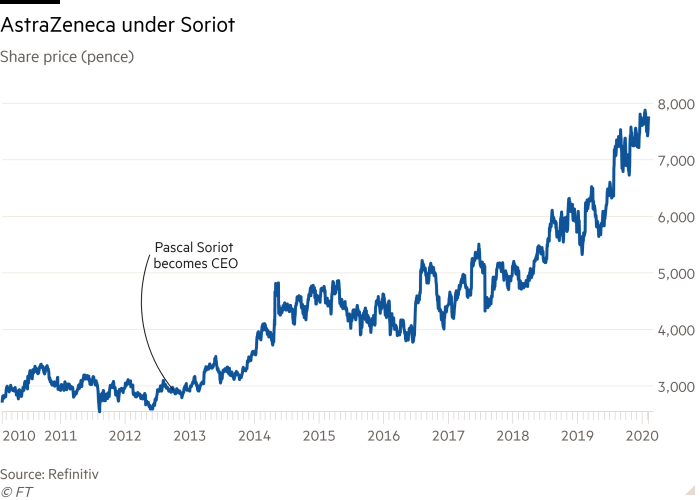

A group that, by his own account, was “about to implode” little over six years ago, is now one of the industry’s acknowledged research and development powerhouses, and, over the course of his tenure, the fastest growing large pharma company judged by total shareholder return.

But to its demoralised employees that resurgence seemed a distant prospect when he was approached to run the business in 2012. He found “an organisation with lots of very good people but . . . that collectively didn’t really know exactly where it was going” and lacked “a clear idea of what was going to right the ship”, he recalls.

Some in the company had lost confidence in its ability to find new drugs, and secure reimbursement amid ever-tighter health budgets , even as patents expired on some of its most important medicines.

Mr Soriot was not short of internal critics as he sought to deliver a research-led renaissance, he recalls. “I remember one of the senior leaders came up to me one day and said, ‘Well, I understand what you plan to do but I don’t think it’s going to work because the R&D team is not that good and hasn’t delivered.’”

He discovered that work had been suspended on Lynparza, an innovative cancer drug, after the commercial team queried the size of the likely market even though it had excited the scientists involved.

A believer in the power of concrete examples to illuminate a wider strategy, he decided to “take a risk” by reinstating it, thereby sending a signal through the organisation that its scientists were doing promising work. The drug is now a blockbuster for Astra, on course for more than $3bn in sales by 2023.

But as he began to implement his transformation plan, he was abruptly plunged into a crisis, when Pfizer made an offer for the company valuing it at a substantial premium to the prevailing share price, and he had to fight to convince investors it should remain independent.

Looking back, he views the approach as a catalytic event that persuaded even internal sceptics to embrace his strategy, accelerating a process that might otherwise have taken far longer, if it had happened at all.

“When a group of people that feel they belong to the same community experience a common threat then it strengthens the community even more,” he says, making clear the affair had revived memories of more physical battles in his youth.

The need to identify a collective organisational purpose remains one of his guiding tenets and, he suggests, underpinned the turnround he has delivered at Astra.

“You have to inspire people to achieve something and then to do it together. You can’t go to the people in the labs here and tell them, ‘we are here to increase the share price’. They couldn’t care less.

“It is a sort of a biomarker of the collective success of the organisation but it doesn’t really motivate people that much. So you have to say, ‘OK, what are we here for, what are we trying to achieve, what do we stand for as a company?’”

The bid repelled, there followed several testing years in which Astra’s shares languished far below the price that Pfizer had offered back in 2014 and cast-iron blockbusters remained elusive.

The Pfizer fight had been “exhausting”, he acknowledges, and afterwards many investors and analysts were vocally critical of Astra’s slow return to growth. “That influences the perception the internal audience has of our chances of success”, he admits.

When in 2017 a new drug combination for lung cancer, in which the company had invested enormous hopes, failed in a clinical trial, wiping £10bn off Astra’s value, the group’s fortunes seemed to have reached a nadir.

He insists, however, that he never felt his job was under threat, receiving “questions but no serious criticism” from board members.

Mr Soriot’s term for his own leadership style is “casual intensity”, an approach he dates back to a period as chief executive of Genentech, the Californian biotech, whose laid-back and collaborative internal culture is combined with a hard-driving approach to finding breakthrough medicines.

“One thing I try to do is not take myself too seriously, be relaxed and approachable, but at the same time be intense and competitive in how we operate,” he says.

Encapsulating the sense of purpose he believes he has inculcated at Astra, he says: “It’s gone from what we were focusing on six, seven years ago which was, ‘OK, what is the market share of this product and how much cost savings are we going to make and how much share buy-back?’ to ‘We are here because we are science-driven and we want to eliminate cancer as a cause of death.’”

True to the humility and work ethic he learnt from his modest upbringing, he is convinced that leaders are made, not born, with a youthful sense of destiny an unreliable indicator of future achievement: “I think leadership is a sort of collection of traits and skills that you build over time . . . without thinking ‘I’m going to be the prime minister of the UK.’

“Just make yourself better to get to the next level.”

Three questions for Pascal Soriot

Who is your leadership hero?

Greta Thunberg, as she has a clear mission that she is passionate about — and she speaks bravely. Her advocacy has been a huge inspiration to me. Once we saw what was happening with the Australian bushfires it was clear that there is a climate crisis and that we all need to act now. This is why we brought forward our plans to make our company zero carbon by more than a decade.

If you were not a CEO, what would you be?

I would be a horse vet, which was actually my first job. I love horses.

What was the first leadership lesson you learnt?

I grew up in a modest neighbourhood which means I rapidly had to learn the importance of doing the right thing, of leading by example and of surrounding yourself with people who share your values.

Comments