Asian dynasties: Battle for the soul of Singapore

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

To those who criticised the generous salaries offered to his ministers, Lee Kuan Yew — the politician credited with transforming Singapore from a resource-poor tropical port into one of Asia’s wealthiest nations — had a simple retort.

“You know, the cure for all this talk is really a good dose of incompetent government,” Singapore’s founding father remarked in 2007, a reflection of his fear that standards would slip. “You get that alternative and you’ll never put Singapore together again: Humpty Dumpty cannot be put together again.”

Two years after his death, an outbreak of feuding among the Lee children has highlighted faultlines in the gleaming city-state he shaped. In a very public row that has captivated Singaporeans, Lee Hsien Loong, the prime minister and son of the founding leader, has been accused by younger brother Lee Hsien Yang and sister Lee Wei Ling of failing to honour their father’s wishes and harbouring dynastic ambitions for his own son.

The dispute has focused attention on the tight circle of power in Singapore, where the state has become enmeshed with a single family. In a country that prides itself on meritocracy, Lee Kuan Yew’s son is only the third prime minister, and his son’s wife Ho Ching heads Temasek, the sovereign wealth fund.

The Lee family drama has come at a time when the city-state was undergoing a crisis of confidence. Since it unexpectedly became an independent state in 1965, Singapore has achieved extraordinary wealth by leveraging its strategic location, specialising in niche industries and promoting itself as a neutral and efficient hub which connects Asia to the rest of the world.

Yet in the era of Donald Trump as US president, Singapore worries how a small nation that has thrived in an era of trade liberalisation and openness will prosper if globalisation starts to go into reverse. And its leaders fret that its advantages are slowly disappearing in the face of competition from a more prosperous and assertive China.

The growing doubts in Singapore about both its leadership and direction were captured in an article by Kishore Mahbubani, an academic and former diplomat for the city-state, who argued that the country needed to behave more humbly because it is a small state that lacks leaders of Lee Kuan Yew’s stature.

“We are now in the post-Lee Kuan Yew era. Sadly, we will probably never again have another globally respected statesman like Mr Lee,” he said. “As a result, we should change our behaviour significantly.”

The headline figures do not look too bad for Singapore. The central bank predicts growth in gross domestic product of 3 per cent this year. The unemployment rate for residents remains at 3.2 per cent in the first quarter.

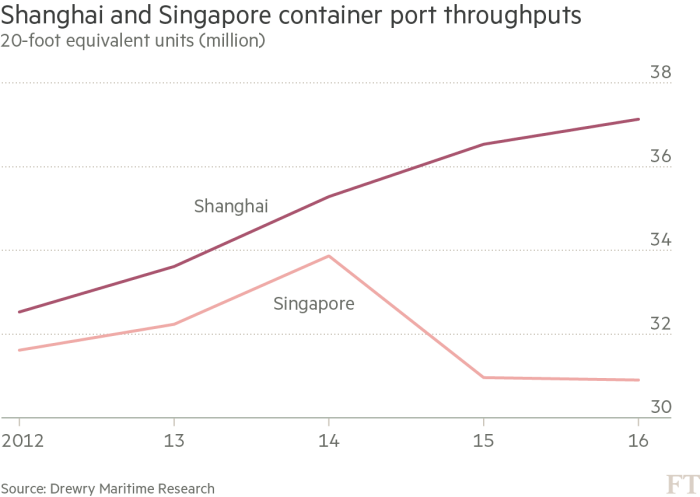

But it has faced a series of alarming indicators about the key components of its economy. Singapore Airlines, once the passenger airline industry’s pacesetter for innovation and standards of luxury, reported an unexpected quarterly loss in May after coming under intensifying pressure from competitors; the Singapore stock exchange has seen only two initial public offerings on its main board this year, the bigger of these raising S$174m ($126m); and container volumes at Singapore’s port — still the world’s second busiest — were flat year on year.

The rise of China is a common theme behind many of Singapore’s pressure points. The flag carrier has suffered as Chinese tourists take domestic airlines on nonstop flights rather than stop over in Singapore; mainland Chinese companies have preferred Hong Kong to Singapore for their listings; and the port of Shanghai is booming while container traffic through Singapore stagnates.

For many analysts, these setbacks are signs of deeper problems. Manu Bhaskaran, a Singapore-based partner at Centennial Group, an economic consultancy, says: “The single biggest challenge to Singapore is the value proposition, which is a combination of competitiveness — including costs — and how the city has chosen to position itself.”

Pointing to Hong Kong’s capacity to use mainland China as a base for low-cost manufacturing and to stoke demand, he adds: “Rivals such as Bangkok and Hong Kong are gaining economies of scale and scope from their increased integration with dynamic immediate hinterlands, something which we simply do not have.”

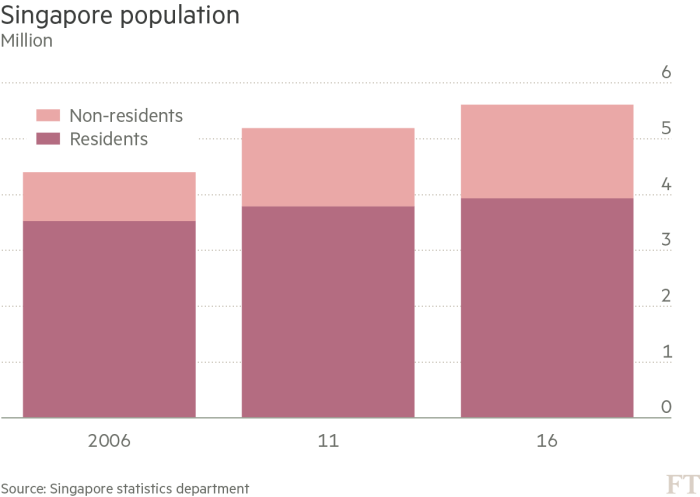

Singapore is grappling with a confluence of negative trends. The city-state has one of the lowest birth rates in the world, at 1.2 births per woman according to the World Bank, while the flow of migrant labour has been tightened in the face of popular discontent.

The resulting labour crunch has meant that nominal wage growth, at more than 3 per cent annually since 2010, has raced ahead of productivity growth, which has languished at about 0.4 per cent for the past five years, according to research from Maybank.

High costs have made investment in Singapore less attractive. Singapore saw a 13 per cent drop in foreign direct investment inflows last year, falling to $62bn, the lowest level since 2012, according to Unctad, the UN trade and development agency.

Government advisers fear the rise of nativist politics across the world will be particularly damaging for Singapore, which relies on external demand for two-thirds of GDP. An advisory economic panel to the government warned of a “dark shift in mood” away from globalisation, in a report published in February. “The anti-globalisation trend will undermine international trade, hurting all countries, but particularly small open ones like Singapore,” it said.

Singapore has adapted to change in the past. In the 1990s, it shifted focus from manufacturing to chemicals and electronics, and developed biomedical science, an industry that now accounts for about 5 per cent of GDP, according to the Economic Development Board, a government agency. But the speed of technological disruption presents it with an unprecedented challenge.

Business people and analysts fear that Singapore’s homegrown workforce lacks the flexibility to adapt to change in sectors like law and accounting, where some functions are likely to be transformed by artificial intelligence.

“The general workforce in Singapore is great,” says Declan O’Sullivan, managing director of Kerry Consulting, a recruitment agency. “But their greatest strength is adherence to process, teamwork and a work ethic. Where process is automated, the role of human capital must be to add value in terms of creative thinking.” Singapore’s policymakers are conscious of the risks but analysts say government incentives to innovate have often been poorly targeted. Government funding to tech start-ups has lacked discernment and thrown a lifeline to many slow-growing “zombie” businesses, according to researchers at the National University of Singapore.

A Productivity and Innovation Credit scheme, unveiled in the 2010 budget, has been plagued by widespread fraud. Among those convicted was a director of a company that makes robotic ice-cream kiosks, who was fined in April for wrongfully obtaining a S$60,000 payout.

But the city-state retains powerful advantages, analysts say, citing the stability of its governance in an uncertain region, the depth of professional skills and the rigour of its education system.

Tax incentives, including temporary rates as low as 5 per cent for companies setting up regional headquarters, its efficient infrastructure and the high quality of life on offer to expatriates also appeal. Western executives dismiss the notion of basing themselves elsewhere, noting the 1MDB scandal in neighbouring Malaysia and Indonesia’s jailing of its most prominent Christian politician.

Ho Kwon Ping, executive chairman of Singapore-based hotel operator Banyan Tree Holdings, even argues that the anti-globalisation trend may play to the country’s advantage.

“People have begun to realise that locating in an area that is volatile like the UAE and [Gulf] economies might not be so great as it once seemed, while a bigger country has national politics,” Mr Ho said, citing the impact of Brexit on banks based in London. “Our small size and stability becomes an advantage; a safe haven in stormy times.”

But for the first time, a spell of economic weakness is coinciding with a time of broader political vulnerability. The Lee family, which has overseen Singapore since independence, has been split by the infighting over the legacy of the country’s founding father.

The trigger for the dispute, which has simmered since Mr Lee’s death in March 2015, is the family home, a bungalow near Orchard Road that the country’s first prime minister wanted demolished after his death. Lee Hsien Loong, the current prime minister, has recused himself from a committee set up to consider the fate of the house, but his siblings accuse him of conspiring to maintain it in an effort to feed off his father’s credibility. He has denied the various allegations levelled by his siblings.

The conflict has arisen as Singapore prepares for a transition to a new generation of leaders, the first with no direct memories of the country’s colonial past. The premier is serving his third term and is due to step down after the next general election, due by April 2021.

The dispute has sharply divided opinion in Singapore, splitting loyalists to the prime minister from those who believe a dying man’s wishes must be fulfilled.

Michael Barr, author of The Ruling Elite of Singapore, suggests that political mismanagement has magnified the impact of the Lee family feud. The current leader, who took office in 2004, presided over a surge in Singapore’s migrant population, which powered key industries such as rig-building but also caused disquiet among citizens.

After its narrowest-ever election victory in May 2011, the ruling People’s Action party was forced to confront public anger over housing costs, overcrowding on public transport and a perceived over-reliance on migrant labour.

Mr Barr says: “The only reason Lee Hsien Loong is so keen on maintaining links with his father is that his government’s own record has been so weak and patchy. After he took over, immigration increased by a drastic amount and they let infrastructure slide.”

Recognising the risks of a long-running feud, the younger Lee siblings offered to call a truce last week, agreeing to an offer by the prime minister to settle the affair privately. But the squabble has raised uncomfortable questions. Until now, Singapore’s leaders have vigilantly defended their reputation in court — successfully suing foreign media, local bloggers and opposition politicians for claims that cast the slightest shadow on their integrity.

But on this occasion, the allegations of nepotism arose from within the family, leaving its rulers in a bind; attempting to gag the prime minister’s siblings would vindicate their claims of oppression, while doing nothing would imply that the Lee family enjoys privileged status.

“Three generations is about the conventional lifespan a family business tends to last before the grandchildren start squabbling,” Mr Barr says.

Comments