Nicolas Ghesquière on fashion past, present and future

Simply sign up to the Fashion myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

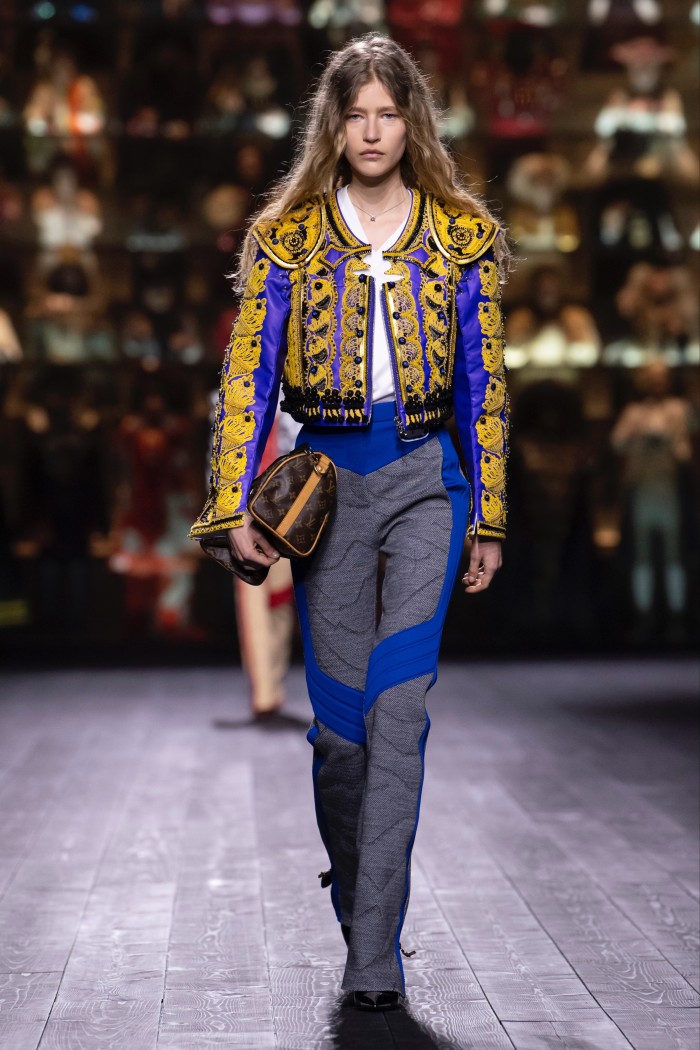

Few of the 800 guests will have realised, on walking into the Louis Vuitton show space at the Louvre on March 3 2020, that they themselves might be participants in a strange historic moment. The catwalk show marked the end of a febrile, nervy season that continued to press forward even while the spectre of the pandemic inexorably closed in. An odd blend of anticipation and relief hung in the air. And yet, as is to be expected from one of the biggest brands in the industry, the house still put on a magnificent performance: the clothes were a mash of influences including pinstripe suiting, ski parkas, moto corsets and tiered petticoats – all plucked from different eras and set against a twinkling tableau.

As the first chords broke, a chorus of some 200 extras, each dressed by the costume-maker Milena Canonero, appeared wearing sweeping looks from centuries gone by. In the gloaming of the auditorium it looked as though the artworks in the Louvre had been magicked into life and the audience watched as fashions past, present and future seemed to momentarily collide.

For Nicolas Ghesquière, creative director of womenswear at Louis Vuitton since 2014, the show was the culmination of two years’ planning. He explains: “I wanted to explore the sensation of what I would feel if someone from the past could have a look at what I’m doing now. It was a little ghostly maybe, but that was really the intention, this clash of the clock. I knew the moment was right.” What he couldn’t have known then was that the fashion show – with its cast of hundreds, its audience packed into the seating, its celebrity attendees – might itself be consigned to history. With his 46 autumn/winter 2020 looks, he may have staged the last great fashion spectacle of its kind.

Days later, on a trip to Los Angeles where Ghesquière was due to attend a wedding, the world started shutting down. The Met Gala accompanying the annual Costume Institute’s exhibition About Time: Fashion and Duration, of which he was a co-host (and a theme his autumn/winter 2020 show had surely had in mind), was cancelled. The exhibition is currently postponed. In the weeks that followed, the fashion industry entered a state of crisis, with the pandemic upending everything from supply chains to distribution, manufacture to design. Ghesquière quickly reconfigured the Vuitton atelier to work with social distancing, production meetings went digital and the fashion show – that great marketing totem of the business – for the most part went online.

Things are still volatile. At the time of writing no one knows what form the women’s shows will take this autumn, who will attend them, and if indeed there will be any shows at all. Many retail points are still closed. The industry is navigating a path in which consumer confidence has tumbled – McKinsey analysts have warned that fashion sales will shrink by up to a third this year. Not surprisingly, many are looking to mega‑brands such as Louis Vuitton (whose sales have remained more stable than the vulnerable smaller independent fashion labels) for direction. As one of the largest luxury brands within the LVMH mantle, making up an estimated 50 per cent of the profits at a group which made a record-breaking €53.7bn in 2019, Vuitton’s decisions set a precedent for how other brands behave. Has the pandemic been the harbinger of lasting change within the industry, or will things go back to the way they were?

Ghesquière is in no doubt that this moment has marked a turn in his creative journey. At 49 years old, the French designer has been a creative force within the industry for more than 30 years; he started working at Jean Paul Gaultier aged 18, and was appointed to head the house of Balenciaga at a precocious 25. “There is no room for going back to what things were,” he says. “And while we have the tendency to want to go back to what was, I think that would be our worst mistake.”

The designer is speaking from his Paris studio, a former apartment he turned into a private workspace a few years ago, where he works when he’s not at Vuitton. He has spent much of the past few months at his country home just outside the city, a place he bought 14 years ago but where, until recently, he had spent very little time. During lockdown, he corralled a few close friends together, stayed off social media and tried to focus an already busy mind.

“It’s not that we weren’t thinking enough before,” he says of his creative reset, “but I think the time was consumed with this crazy rhythm of proposing collection after collection, and it didn’t allow us the proper time to focus on what was necessary – [the issue of what was] ethical, sustainable, the problem of waste. It wasn’t right. I’d rather work more on less product than too quickly on more product. That doesn’t mean we’re going to sacrifice the economy, but I think it’s been a wake-up call.”

Before the pandemic, many designers had lamented the stranglehold of the fashion cycle, the pace at which they had to deliver, and a manic working schedule that found them flying around the world. Not that Ghesquière is complaining. But the global slow-down has proved that there are other ways to work. “I had incredible cruise collections with Vuitton, where we would take 600 to 800 people and do a fashion show in Kyoto, in Rio, in New York. And it was extravagant – and it was necessary, because the demand for fashion was very high as well. But I don’t want to do the same any more. I know that this is over. It was incredible, but I know what I’m going to do next.”

For Ghesquière, the future means going back to fundamentals: to simplify the process and to stop overcomplicating things. “I said to my design team, ‘We’re not going to do another 300-piece collection, it’s not going to be that. So I want you to come back [after the lockdown] with the things in which you really believe. I’d rather have two ideas instead of five. I think, mentally, we had all started to feel a bit lost at times, because that’s the reality of manufacturing. But this was an opportunity to exchange a lot about our feelings and see what themes emerged.”

Unsurprisingly, his designers came back with many themes in common. The subject of safety was predominant. “Many of the team returned with an expression of protection,” says Ghesquière. “But, in fashion, ‘safe’ can mean a lot of different things. Being safe in fashion doesn’t necessarily mean wearing overalls, but the question of the function was very important in the discussion we had.”

Freedom of movement, athleisure, the working-from-home wardrobe were also fairly typical contributions, but other conversations also threw up more unexpected ideas. “There was a big interest in a certain kind of graphisme,” says Ghesquière, “something very positive, very optimistic, very colourful, very bright.” Perhaps surprisingly, among the team there was a feeling of exuberance. Says Ghesquière: “The future of fashion is not something that is tepid for me.”

If the designer feels a historic resonance with another decade, it’s the 1920s – a period of youthful energy, creativity and crazy hedonism that also followed a pandemic – rather than any time in more recent history. “Remember after the 2008 economic crisis when fashion was questioning its voice and thinking everything should be much more conservative? I don’t think that at all this time. The voice of younger people is very bright, it’s happier and, politically speaking, it’s more powerful than before.” Moreover, with fashion poised on the brink of a new decade, Ghesquière says that the mood and silhouettes that will characterise the 2020s are still waiting to take shape. “Where we are is not defined yet. The moment is only rising now.”

Ghesquière has long been a fashion trailblazer. At Balenciaga, where he worked for more than 12 years, he created some of the strongest looks of the 2000s. His high-waisted jodhpur trousers, worn with a military blazer, became one of the most familiar fashion silhouettes of the era; his athletic takes on retro-futurism are indelible as well. He calls his aesthetic “hybridisation” – a design practice that has always mashed a fusion of oppositional ideas. And at Louis Vuitton he has continued to cherry-pick his influences from a sweep of different eras, taking in ’80s Paris club kids, 18th-century frock coats, boxing shorts, ’70s suiting and tunic dresses best suited to the Starship Enterprise. Along the way, he’s helped to nurture a new wave of creative talent – most significantly his former studio head Natacha Ramsay-Levi, who now leads the house of Chloé, and Julien Dossena, creative director at the Puig-owned Paco Rabanne. Rather than predicting the death of fashion, he sees the current crises – both Covid-related and in the global social activism that has subsequently arisen – as an impetus for creative revolution. “It’s a great stimulation for us to be living in this moment,” he says. “Breaking boundaries, breaking categories. It’s quite violent, what’s going on around the world. And the transformation that goes with violence is always difficult. But I really want to be part of what happens now.”

This time has also encouraged him to think more sustainably as well. As fabric manufacture was so compromised by the pandemic, Ghesquière found himself returning to the storeroom to use materials they already had in stock. “We had been talking for years about the process of waste and how to be more careful, more attentive, but with the crisis we had to accelerate that process. And so, for our cruise collection [unveiled in July, and in-store this winter], we finally went into our stock fabric and created this small collection, 60 per cent of which was done with fabric that we had – not only to prototype but to produce the whole collection. It was one of the big changes for this season, to put things into action and approach the situation with a positive and proactive attitude. I found it very interesting. It’s not that I’m trying to find every positive in the crisis, but it felt very good to use resources that were available within a very short distance. And not just fabric – human resources too.”

It’s bold talk to speak of sustainability, using deadstock and culling one’s collections when you’re sitting at one of the world’s most lavish labels; a brand that has built its reputation in the name of pure unfettered luxury, aspiration and unapologetic wealth. But Michael Burke, Louis Vuitton’s CEO, is quick to echo much of what Ghesquière is saying.

“What the pandemic has done is bring to light a whole host of issues that were already in the undercurrent of what people were talking about,” says Burke, on a Zoom call from Biarritz. “We had posted record-breaking results for a full year before the pandemic, but things were spinning out of control. This period of time has been an opportunity – across the group – to concentrate on what makes each house its own. This crisis has made it very obvious what is noise and what is substance. This has reminded us of the basics of what counts.”

For Burke, one of the most positive changes has been the emergence of an executive structure that sees less “trickle down” from Paris. When we speak, he is finessing the details on the Vuitton menswear presentation that is being produced between the LV teams in Shanghai and Paris; a show subsequently watched online by 104 million people and an event, he later tells me, that precipitates the brand’s “best-ever weekly sales”. He is adamant that future business opportunities will be more shared partnership events. Which I assume is shorthand for saying that the future lies in Asia.

“We have for too long conceived of things in the west and then, when they have been successful, run them sequentially in other places in the world,” Burke says. “The paradigm has changed. The markets in Shanghai or Korea are so matured and highly developed that it means creative activities must be shared now. Sequential doesn’t work any more.”

In the meantime, consumer relations are bound to become increasingly personal. Stores will host more private client sales events, and trunk shows (those great in-store sales events of the ’70s) will become the norm. The show in Shanghai will set a template for staging consumer “interactions” based around more local points of sale. And the digital drive will be ongoing. Consumers have happily switched to online shopping throughout the crisis – and the pressure to innovate further on digital platforms will remain the same.

But while Burke sees shows being far smaller and more local until we find a coronavirus vaccine, he’s less convinced we’ll see fewer products in collections to come. “It doesn’t mean we’ll be producing less products necessarily,” he argues. “Because now is a time when there are more brands on the market, more players and more people at the table. To suggest there should be less product feels a little exclusive to me.”

Not surprisingly, the CEO of Louis Vuitton is not a fan of hair shirts. “Less consumption is another philosophy,” he says of the general reset that favours quality over quantity. “But making better products is something in which I do believe.”

As to the fate of the fashion show, Ghesquière remains uncertain. “I’ve spent most of my life doing two shows a year, more since I’ve been at Vuitton. I’ve spent 30 years with the rhythm of fashion shows in my life. And I love a show. It’s a very happy moment – but I don’t want people to forget that the show was always a professional moment. The most magnificent work session, but a work session all the same. It might take another shape in the near future, but I still believe we will need that live performance. It’s hard to do something as relevant as a girl walking in a room. I don’t think there is a magical formula yet, but we will find something that will have a sense of what we do.”

The Louis Vuitton show of the future. It may not feature a chorus of 200 costumed singers. It may not play to an enormous crowd. But as long as Ghesquière has a part in the theatre of fashion, the drama will live on.

Comments