Indian fintechs face big test as economy feels the heat

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Growing up in Mumbai in a family of entrepreneurs, Hardika Shah knew of the troubles small businesses face in India. “I saw the constant struggle for capital,” says Ms Shah, who returned to the country from the US almost a decade ago to start Kinara Capital, a small-business lender.

So much had changed in India, except for an old, familiar problem: “I recognised that while the economy is booming and every engineer is out getting a job, the small-business owners were still struggling,” she says, speaking from her base in Bangalore, India’s tech hub.

Kinara is now one of India’s fastest-growing companies, providing loans from $2,000 to $25,000 to small businesses in the manufacturing sector, with the average loan amount being $5,000-$7,000.

The lender ranks 64th on this year’s list of high-growth companies in the Asia-Pacific region after delivering a compound annual growth rate in revenue of 126 per cent between 2015 and 2018.

Yet, as the coronavirus crisis takes hold, many Indian businesses face an immediate threat to liquidity, demand and ultimately growth. Fintech in particular is braced for a storm, with many lenders reducing loan sizes and fleeing to higher-quality borrowers to limit risk.

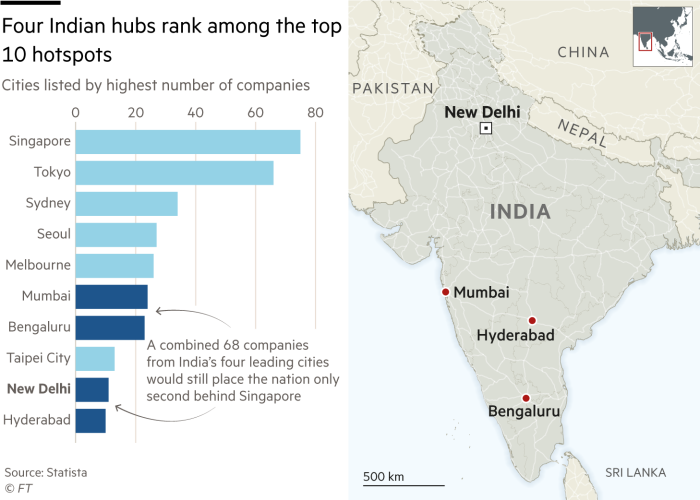

With 140 companies, India produced the highest number of entries on the 500-strong ranking. Yet although four of the top 10 Apac cities on the list by number of companies are Indian — Mumbai, Bengaluru, New Delhi, Hyderabad — if combined, the total would still only come second to Singapore. (As with the 2018 ranking, China is excluded due to difficulties in verifying company data.)

Comparatively lower tax rates elsewhere have helped lure some businesses away from India. Many companies often incorporate outside of the country to take advantage of more flexible intellectual property and employee stock ownership regulations, says Madhur Singhal, managing director of consulting firm Praxis Global Alliance.

“The legal and taxation construct is a lot more flexible outside India,” says Mr Singhal, despite New Delhi working to create a better environment for businesses.

In 2017 India attempted to simplify the tax system with the goods and services tax (GST) and has moved to formalise digital payments. These steps are “incremental, but in the right direction”, he adds.

India has a large talent pool of expertise in knowledge-based industries ranging from IT to life sciences. With a diverse population of 1.4bn, the second-largest in the world, companies that succeed in India are equipped with a human arsenal to help them thrive in other markets.

Take LogiNext Solutions, a company ranked 44th on the list, that provides software for home delivery services. It started in India but now 85 per cent of its business is overseas. Clients include McDonald’s and Singapore Post, the city-state’s national postal service provider.

“There are so many languages and infrastructure breakdown points in India that once you [overcome these and] build a product, then you naturally end up building it for the world,” says Dhruvil Sanghvi, LogiNext chief executive.

Mr Sanghvi credits India’s mobile revolution for part of his company’s success. The launch of Reliance Jio, whose cheap mobile internet services has won it more than 370m Indian users in just three years, has made calls and data affordable to the masses, opening up previously untapped digital markets.

“Customers are choosing not to go to stores any more,” he says, “ecommerce is increasing day by day.”

A rapidly growing upper-middle class is another significant trend for start-ups. “Affluence is on the uptick,” says Nimisha Jain, managing director and partner at Boston Consulting Group in Gurugram, near New Delhi. This group — roughly 15 per cent of India’s population — is expected to account for 40 per cent of total spending by 2028, she adds.

Across India, companies are “creating a set of very new and different business models to go after these consumers”, she says. Projected areas of growth include convenience apps such as food delivery, health and wellness, and education, adds Ms Jain.

Online banking is aiding this shift. “The digital part of this is absolutely key,” says Kinara’s Ms Shah. Technology helps her company deliver money to a customer’s bank account in less than a week — a near miracle for those used to India’s sluggish bureaucratic system, she explains.

Small entrepreneurs contribute a third of India’s manufacturing output, according to the Confederation of Indian Industry. Yet many lack the financial records or credit history to access traditional financing. New lenders like Kinara are part of a wave of start-ups using technology to comb digitised business records and entrepreneur profiles to enable low-cost credit assessments and underwriting.

“There has been a step up on overall economic activity in India, leading to a greater need for SME financing,” says Ausang Shukla, managing director of corporate finance at brokerage Ambit.

“There has been a big boost in lending to the so-called underbanked,” he adds, referring to individuals and businesses that have limited access to financial services. India has the world’s second-biggest population (190m people) without access to bank accounts, according to the World Bank.

OfBusiness, which ranks 17 on the list with a 2015-18 CAGR of 243 per cent, has also seized the opportunity to fill this gap.

“We wanted to be working-capital financiers,” says Asish Mohapatra, co-founder of the company based in Gurugram. “We are hardcore lenders and asset builders.”

The company provides manufacturers with capital for raw materials and offers other services such as marketing. In its latest fundraising in 2019, it secured $35m from investors such as Norwest Venture Partners, in a round that valued the company at about $275m. “Because of technology our profitability is high,” says Mr Mohapatra.

After several years of strong economic growth in India, with GDP rising annually by more than 5 per cent on average, companies face a major test from coronavirus. Analysts expect it will force consolidation as businesses face an unprecedented slump in demand, subdued growth and liquidity constraints.

Ms Shah is no stranger to disruption. When New Delhi introduced the GST tax reforms in 2017 it caused chaos among her clients, as outstanding tax refund claims left many borrowers unable to meet their loan repayments.

Yet she says the challenge posed by coronavirus is far more serious, with entire supply chains disrupted and industries frozen as a result of the lockdown. Kinara’s loan disbursements are on hold while the nation is on lockdown.

“The economic impact of Covid-19 is far greater and has come with a velocity that was unexpected,” she says. “My hope is that the government will provide the necessary stimulus.”

Ms Shah has faith in the resilience of small business, however, describing them as the “backbone” of India’s economy. “We are ready to hit the ground running once everyone begins to resume normal operations.”

Comments