Christian Jankowoski, at home in Berlin

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Artist Christian Jankowski arrives at his home a little late for our meeting. He’s been out buying a vintage Italian lamp at the flea market. He thrusts it forward for inspection: “It may be iconic, but I don’t mind if it’s not.” A make such as Artemide comes to mind, but whatever it is, the shiny black-and-steel contraption will join a small family of lighting peppering Jankowski’s spacious Berlin loft. From a quirky Kalmar Franken Eisglas chandelier (in his regal blue bathroom) to colourful Swiss lamps from the ’70s, the ensemble of forms lends warmth and light to a mostly off-white interior.

Jankowski lives in a quiet area near Kreuzberg, on a tree-lined street not quite consonant with its reputation as the rebel heart of Berlin. And yet Jankowski’s apartment was used as the production set to recreate a portrait of one of Germany’s most extreme radical groups, Kommune 1; a famous photo of naked rebel student protestors was re-staged in the apartment where he now lives. In the ’70s, this part of Berlin was the cauldron of militant politics.

Kreuzberg today is more residential than rock, so it’s somehow perfect for the fiftysomething globetrotter who lives here with his family while carrying out an international career. Jankowski’s work is the subject of a current retrospective at the Kunsthalle Tübingen, and he is juggling the usual load of projects, one of which includes a revitalisation of the city of Lübeck with a council that includes, at his request, a number of elementary school-children; he also has plans to bring the city’s Protestant churches out of their doldrums by placing supermarkets in their naves. Jankowski’s bravura as an intellectual and urbanist is his “détourning” of one reality into the shape of another. His art is a performative practice, where anything can be his material. His is a kind of visual John Cage, allowing reality to be the sound of the work.

In an often-related anecdote, the young Jankowski was initially rejected in his application to the Academy of Fine Arts, Hamburg – he was aiming at music in this period of his life. He even played for the band The Tubes on the song “White Punks on Dope”, but then put his head toward becoming a painter. Jankowski had to abandon that too, however, when he came under the tutelage of more conceptually oriented artists, such as Franz Erhard Walther and Stanley Brouwn. These figures taught him the power of immaterial strategies and how to make art with even the flimsiest of materials, from fabric to the dust of footprints. Art school in the ’90s impressed upon Jankowski a lasting faith in concepts over specific form. He is puzzled when asked to name his own most iconic piece. “It’s breathing, in and out,” he says. “Art is about the exchange, about the trade, about learning about the other.” A social practice, one might even say, though Jankowski is far from unskilled at producing objects.

In fact, he is a major artist as well as a kind of anthropologist or choreographer of social structures, an expert collagist of the real who will take something as well-known as a television series or a luxury yacht and move it by just a notch, so things are not quite as they seem. He’ll redo the plot, supplanting words with laments or adding his own texts, yet all on prime-time television, blurring the boundaries between comedy and tragedy, real and theatre – a kind of Beckettian slippage he has applied to social conventions from religion and commerce to politics.

Jankowski’s uncanny ability to take in the gestures, comments, fashion, music, sets and tropes of anything – from casting a Jesus lookalike to labelling a luxury speedboat art – designates him as one of the most interesting figures in art today, and is somehow reflected in his peaceful loft apartment. From the white Michel Ducaroy Togo couches designed for Roche Bobois to the simple barstools or poured-stone kitchen counter – with a huge crack down the middle (“The worker just thought it was OK like that”) – each element is both there yet inconspicuous, so understated that it becomes evident. In some ways, it is an ostentatious modesty and non-design that Jankowski teaches, an ethic of non‑consumption, a morality of restraint.

“I grew up in Göttingen in the ’70s,” he says. “My parents were in the SPD party, left-leaning and interested in taking their children to museums or on trips.” In the middle of his loft apartment is an enormous grey sculpture of a woman’s manicured hand holding a drill bit. It’s a counter-monument, as many of his works seem to be. “This piece is about the conflation of the working class and bourgeoisie,” he says. In Monument to the Bourgeois Working Class, Jankowski points to the logical impossibility of class warfare, even for some of its theoretical architects. The hand subject is sourced from a photo by Mexican mural painter David Alfaro Siqueiros (1896-1974), himself caught between dreams of revolution and a life of luxury. The work looks extremely heavy – but it’s made of cardboard, wood and polyurethane. Heavy and light are played out in other pieces as well, such as a work in which Jankowski asked Polish heavyweight champions to move some enormously cumbersome – and culturally loaded – bronze historical monuments.

Jankowski seems driven by a plan to subvert authority and enable free discussion. Perhaps it’s due to some epigenetic memories of war, of the injustice of his father’s family being driven from a German-Polish homeland or, even further back, of spice-trading forebears. His interest in opening dialogue and creating a system of democratic exchange is almost mathematical. In one exhibition in South Korea, Jankowski cleaned up a museum installation of the late artist Nam June Paik’s messy studio after it had been shipped from New York to Seoul, producing before and after photographs of the transformation. “I would never have reorganised it if it had been the actual studio of, say Francis Bacon,” he says. “But it was already de-installed and reinstalled, and so I felt free to touch it.”

A visit to New York in the late ’80s impressed the style of loft living on the young artist. He was deeply influenced by the home of his short-term host, the late Sally Gross, a performer in the Judson Dance Theatre. Even though he decided to pursue a life and career from Berlin, it’s the American model of artist-living that dominates both his home and studio. A nod to Donald Judd is as apparent, as are the kind of art spaces that Walter De Maria created in lower Manhattan. Jankowski visited as many of these art spaces as he could, and his Berlin loft and studio are a kind of urban mirror of this Manhattan time.

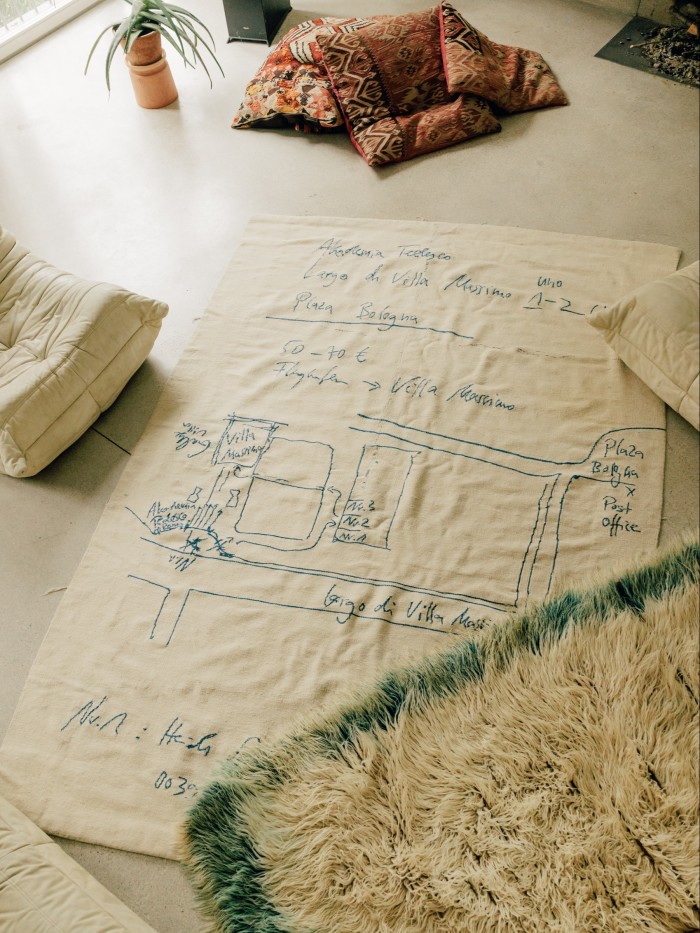

In his Berlin home, bricks are left unplastered on one wall, with the ceiling and much of the remaining walls painted Robert Ryman white. The fashion designer Martin Margiela comes to mind as well – Jankowksi remembers the influence of Margiela’s minimalism ushering in a general aesthetic of non-colour that still persists today. Jankowski’s house hammock – “made of coyote fur”, he is embarrassed to say – is a recent design by Bless. A scattering of kilims, Berber carpets and needlework cushions conjure the Caucasus, and warm up the concrete floor of the living room. In the centre is a carpet designed by Jankowski himself, and produced in Guadalajara, Mexico. It’s both normal-looking and somehow extreme, depicting a hand-drawn map of the artist’s premature departure from a residency at the Villa Massimo in Rome. It’s the kind of work that the artist is known for – transforming the insignificant into the monumental, channelling poetry in the mundane.

The open space is divided by large cypress sliding panels that ingeniously disappear if more space is needed. “They smell good too,” the artist murmurs as he pulls the doors closed. His son’s room leads out onto a large terrace paved with wooden boards. It’s all easy, not too fussy.

Jankowski is about to give his equally minimalist artist’s studio space, nearby, over to his partner, Cristina Vasilescu, a Romanian curator, for a pop-up show. He mentions that Bucharest is the new place to go. He has big plans east, he says, and seems as interested in establishing dialogue with a new generation of curators and retaining his experimental side as he is in wielding institutional power and hobnobbing with government officials.

He drives us to his studio, just a few minutes away on the banks of a Berlin waterway. As he gets into a black Mercedes, he is carrying a black leather briefcase. The Mercedes isn’t the latest one, and the briefcase is a bit floppy – it’s not clear if the artist is serious about either of these props or not. Jankowski has outfitted what was a raw space with a concrete floor, designed Viking ship-worthy wooden beams overhead, and set another cubed fireplace into the wall like a negative of a Tony Smith sculpture.

In both his home and studio are a series of images painted according to Jankowski’s directions by Chinese painters in mainland China. He went to the factory where these custom works are painted and interviewed the painters he commissioned. In fact, he worked with them, asking them to copy his photographs of the unfinished Dafen art museum and fill in the empty walls with a painting of their choice, as if they were the future museum director. The result is the same odd kind of slippage between the theatre of reality and the reality of theatre, a divide that Jankowski straddles very well.

Jankowski has curated exhibitions including the prestigious Manifesta 11, and he exhibits with galleries that include Lisson, Petzel, Klosterfelde Edition and Maccarone. But his work with the public, and the urban planning side of his work, is perhaps more defining as a practice than his ability to fill a space. “I like to work with structures, entire social structures,” he says, “a bit like the Situationists.” He admits a friendship with artists such as Guillaume Bijl who transpose sculptural registers from one context to another, staging sets such as carpet showrooms, exercise facilities, hairdressers and the like, in the white-cube exhibition space of galleries or museums.

Likewise, each element in his studio and home seems both casually situated and yet purposefully chosen. He points to wooden bricks inserted regularly in the exposed walls of his home’s loft. “See, here they just wedged small boards in, to fill in the holes,” he says. He goes around his studio pointing to artefacts that come from South America, such as a vegetable-dyed hammock. “Look, this is all handwork,” he says, “and the dyes are natural.”

When asked if he collects anything, Jankowski shrugs. “Not really, no, I don’t.” A few hours later, he sheepishly confesses to collecting lamps, particularly the Swiss ones he says he can no longer find so readily in the flea markets. His obsession with lighting led him to create his own lamps in Mexico. Produced in clay, and made by hand in Oaxaca, they are perforated like player-piano rolls, and so large, he says, that quite a few of them just blew up inside the kiln. The final pieces are a kind of starry sky voyage in the corner of his studio – a voyage back to the Aztecs, he says.

Does he like fashion? Jankowski is wearing a light blue Vivienne Westwood Oxford shirt. “I only wore black, of course, for years, especially leather. I saw myself as a rocker,” he says, but admits an interest. When he lived in Hamburg, he witnessed the advent of local brands such as Jil Sander, with the city’s fashion temple Thomas i Punkt a necessary pitstop for fashion-conscious artists. This was the beginning of the art lifestyle, and Jankowski was an astute observer of it all. Style, one might say, is one further material in this artist’s arsenal of media. It’s hard to define exactly why it all looks so very good. And that’s precisely why it works.

Comments