Paternalistic leadership offers lessons for western executives

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The author is assistant professor of organisational behaviour at China Europe International Business School

Transformational and empowering leadership styles dominate western discussion on management. But paternalistic leadership is more common in Asia, as well as in Latin America and the Middle East. Business leaders who understand its origin and consequences will therefore be better prepared to work effectively with their international peers.

Consider a classic example of Chinese leadership: Zong Qinghou, the founder of food and drink manufacturer Hangzhou Wahaha Group. He is widely recognised for his paternalistic approach, which combines authority with benevolence and morality. In a joint venture dispute with Danone that concluded in 2009, his style helped to mobilise the Chinese media and to use nationalist sentiment against the French company.

Zong maintained a loyal following over the two years of legal wrangling. He created a media fanfare by showing moralistic concern for Chinese brands and the domestic economy. He remained assertive and authoritarian. Danone, meanwhile, was isolated in a hostile environment.

The dispute drew worldwide attention and prompted intervention by the French government. It remains a textbook example of why executives at multinationals should be better prepared to deal with the paternalistic leadership style.

The Chinese approach is a combination of the authoritarian (asserting absolute authority and control over subordinates and demanding unquestionable obedience); the benevolent (a holistic concern for subordinates’ personal or familial wellbeing); and the moral (superior personal virtues, self-discipline and unselfishness).

Authoritarian leadership derives from the tradition of Confucianism and legalism, which says the father-son connection is fundamental and trumps all other social relationships. A father has authority over his children and holds absolute power and legitimacy. Authoritarian actions, which have been embraced by Chinese emperors for 2,000 years, are widely accepted.

Benevolent leadership stems from the Confucian norm of reciprocity and the five “cardinal relationships”, which emphasise benevolence and mutuality. Examples include the munificent ruler and the loyal minister, the kindly father and the filial son, and the righteous husband and the submissive wife.

Moral leadership has its roots in Confucianism, too. Chinese society was traditionally ruled by people rather than by institutions. People rely on the morality and virtues of superiors and government officials to protect their rights and wellbeing.

But these three dimensions of paternalistic leadership have different consequences. Benevolence and morality can bring positive outcomes for employees and organisations, while authoritarian leadership tends to lead to negative outcomes, such as stress and staff turnover. The strongest result — motivated employees and enhanced performance — is achieved when leaders combine benevolent, moral and authoritarian leadership.

A defining feature of paternalistic leadership is the espousal of a father-like role to provide protection and care for subordinates’ professional and personal wellbeing, while subordinates adopt a childlike role to be loyal and compliant.

Two parenting styles dominate in China: strict authoritarian (the “tiger mother”) and supportive authoritative (the “friendly mother”). Chinese leaders’ styles are imprinted by their family traditions, which may be important influences on them.

At CEIBS, in collaboration with my colleagues Larry Farh, Sebastian Schuh and Katherine Xin, we surveyed 351 Chinese senior executives and their 1,646 subordinates. We asked subordinates to describe their superiors’ leadership style, and executives to describe the parenting styles they experienced as children.

More than half of the business leaders were described as having an authoritarian style and more than 90 per cent as having benevolent characteristics. If they received authoritarian parenting, they were more likely to become authoritarian leaders.

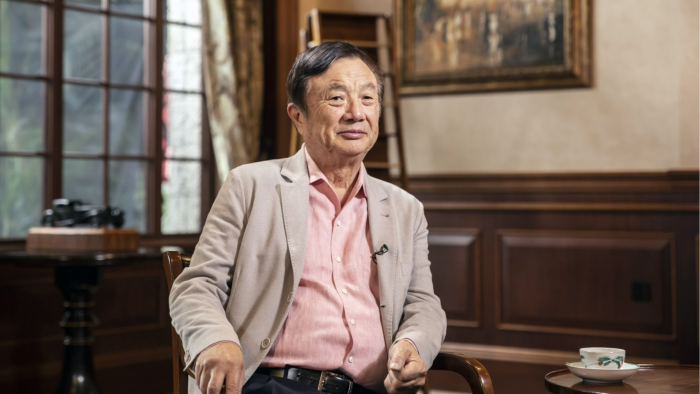

Many Chinese business figures exhibit this approach. For instance, Huawei’s Ren Zhengfei is viewed as a paternalistic leader and his company as a regimented business. His military experience shaped the culture, emphasising well-defined goals, employee devotion, and absolute obedience. Employees are offered competitive pay and there is a high uptake of stock options by staff.

Ren’s leadership style was most effective in the 1980s and 1990s — Huawei’s early years. More recently, however, the suitability of his approach has been brought into question as a new generation of workers arrived with higher expectations. Lack of work-life balance is now a common complaint.

But Ren’s paternalistic leadership qualities came to the fore when Meng Wanzhou, his daughter and Huawei chief financial officer, was arrested in Canada. His role in securing her return to China in 2021 after three years under house arrest was celebrated as a national success, and her image as highly benevolent highlighted the positive qualities of her father’s leadership style.

Such examples underpin the argument that paternalistic leadership can offer a unique contribution to organisations, especially when compared with western styles such as transformational leadership and transactional leadership.

Understanding paternalistic leadership not only helps executives to navigate international business but also helps them to develop their own management abilities. Compared with transactional exchanges that focus on short-term exchanges in business and leader-subordinate relationships, paternalistic leadership adopts a long-term and relational perspective that can cultivate the most motivated, productive and loyal employees, and lead to stronger company performance.

Comments