Lost art: The hunt for vanished masterpieces

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The auctioneer’s hammer falls, the art fair closes, the gallery exhibition is over, the excited babble about the latest megaprices subsides: but what happens next? Where does the work go? A few pieces, increasingly few, find their way on to the walls of public museums. Most go off to live with their new owners under conditions of considerable secrecy. And, these days, an increasing number of important pieces go straight into storage.

That may be a reprehensible trend but at least the work will be safe, and there will be some record of where it is. For one of the oddest things about a culture that purports to care so much about art is that the art seems strangely easy to lose. With no register of ownership, important works can apparently just evaporate into thin air.

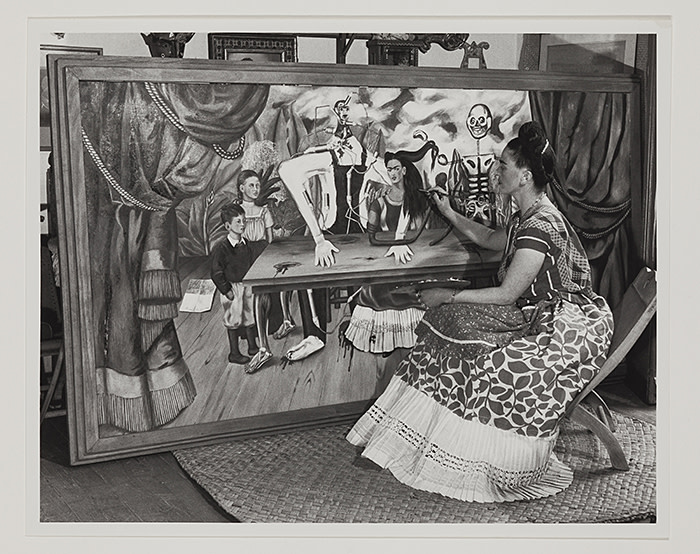

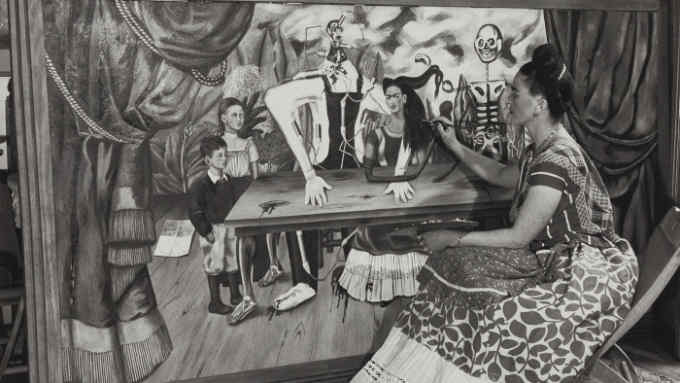

Art history is full of examples of missing wonders, each one an El Dorado for devotees of the artists. Frida Kahlo’s largest known work, “La Mesa Herida” (1940), went Awol in 1955, the year after the artist’s death. She had apparently made a gift of the work to the USSR some time earlier, and at Diego Rivera’s request it was later exhibited in a show of Mexican painting at Warsaw’s Zacheta National Gallery of Art. After that, it was never seen again.

Van Gogh’s “Portrait of Dr Gachet” (1890), which was sold to Japanese businessman Ryoei Saito in 1990 for a then-astronomical $82.5m — the price, when adjusted for inflation, held the record for the most expensive work ever sold at auction for more than two decades — is also missing in action. As is Renoir’s “Bal du moulin de la Galette” (1876), which he purchased the very next day: apparently used as collateral for business loans, then sold on, it is rumoured to be in a private Swiss collection, but there has been no trace of it since 1990. Saito-san declared that he wanted the Van Gogh painting cremated with him when he died: perhaps he did so, as it has not been seen since his death in 1996.

Owners have a legal right to destroy the work they purchase. But not, in most people’s eyes, a moral right. Clementine Churchill’s destruction of Graham Sutherland’s 1954 portrait of Winston (its subject hated it) still rouses strong feelings; and as we are busy celebrating the Rockefellers as great collectors there is little mention of the fact that they had a magnificent 1934 fresco by Diego Rivera chipped off the walls at Rockefeller Center in New York. Its politics were too radical, they claimed: one can only think that, in commissioning Rivera in the first place, they might have known what they were getting into.

And the destruction by the Taliban and Isis of irreplaceable archaeology and art in the areas under their control evokes almost universal outrage.

Artists sometimes do it too: Botticelli, under the spell of the rampaging fanatic Savonarola in 1497, dragged some of his own works to the pyre in the original Bonfire of the Vanities. “Primavera” and “The Birth of Venus” were, wonderfully, safe elsewhere during this moment of madness, but who knows what was lost?

These cases and more are examined in Noah Charney’s fascinating but often sobering The Museum of Lost Art (Phaidon). Such a museum, as Charney imagines it, would “contain more masterpieces than all the world’s existing museums combined”. This might seem a wild claim until we read such statistics as that lost works by Caravaggio alone number between eight and 115.

Thefts, too, often end in sad stalemate: thieves may be caught or ransoms successfully negotiated, and the works salvaged, but several famous cases remind us that it is not always so. In 1990, Boston’s Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum suffered a mysterious burglary, when thieves made off with treasures including a Rembrandt, a Manet and a Vermeer — the latter a particularly sore loss, since there are so few extant works by the artist. Despite sleuthing, a proffered reward and a flurry of press, the whereabouts of these pictures is still unknown. We just have to hope that the Vermeer is out there somewhere, still intact.

Charney divides his web of intriguing anecdotes into sections such as “Theft”, “War”, “Accident”, “Act of God” and more. Some case histories are uplifting: the rediscovery in the 1930s, for instance, of the glittering mosaics of Istanbul’s Hagia Sophia (at least those Islamic conquerors preferred covering them over to wholesale destruction).

Heartening too are the ways in which technology is now harnessed to traditional curatorial expertise to rediscover and reappraise works that have led a hard life: damaged, badly cleaned, overpainted or whatever. A recent famous case was of course Leonardo’s “Salvator Mundi”, “lost” for centuries because it had been so thickly overpainted.

Detective work, in the arts, especially in the Old Master field, is a keen sport these days, with professional connoisseurs perpetually on the hunt for “sleepers”, or works whose real identity and quality have been obscured. Questing for lost works can consume lifetimes, or take official form — as when the government of China set out to find the magnificent bronze animal heads from the zodiac water clock of Beijing’s Old Summer Palace, stolen during the Opium Wars in 1860. The rat and the rabbit turned up in the collection of Yves St Laurent, and were bought (after some detours) by Christie’s owner François Pinault, and gifted back to China. But if anyone spots a dog, a snake, a dragon or a sheep or a rooster . . .

The reasons why art is lost are not always nefarious, as Charney makes clear. Lack of care, changes in taste or morality, accident, poor technique, jealous spouses, sheer ignorance . . . the circumstances are many. But as another trove of works leaves the booths of Art Basel, those who advocate a register of ownership for valuable works will be interested in this book.

Follow @FTLifeArts on Twitter to find out about our latest stories first. Subscribe to FT Life on YouTube for the latest FT Weekend videos

Comments