Can we overcome the curse of the single-use sachet?

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

In the Philippines, a social enterprise called Green Antz Builders has developed a system to turn the small plastic sachets that wash up and litter the archipelago’s beaches into dark grey bricks, which can then be used to build schools and homes.

The start-up pays people from local communities to gather up the empty single-use packets of shampoo, toothpaste, detergent and coffee that have become a waste scourge and turns them into something useful.

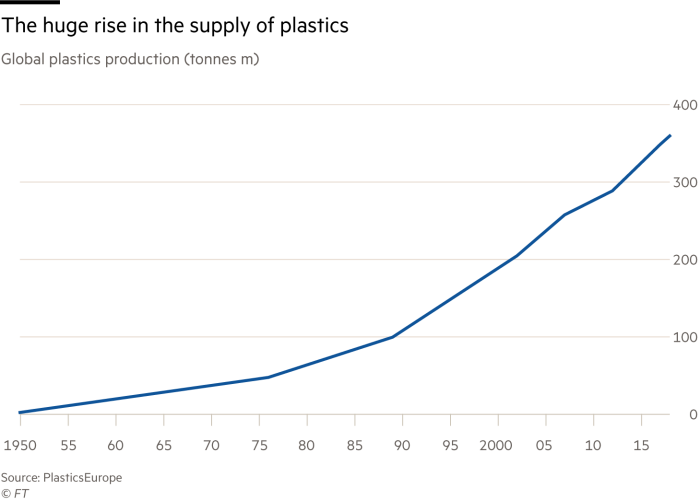

The Green Antz project is an elegant solution built on the principles of the so-called circular economy, which refers to a system in which materials and products keep their value by being reused or recycled rather than thrown away. But its small scale means that it cannot offset the damage caused by consumer goods giants such as Nestlé and Unilever that continue to market products in single-use plastic packaging.

The sachet, which was created to serve low-income people in developing countries, has become a symbol of the global plastic crisis. Given their small size and plastic-metal laminate composition, it is not economical to recycle sachets; instead they often leak into the environment, adding to the plastic clogging the oceans, or ending up in landfills.

The companies say they are looking for fixes, such as experimenting with new designs and materials, piloting reuse schemes, and funding the development of advanced recycling technologies. But none has agreed to phase out single-serve sachets, on the grounds that they facilitate access in poor countries and that alternatives could cause even greater greenhouse gas emissions.

Whether the industry can fix the sachet problem will be a key test of whether it is really possible to create a circular economy for plastics — and of whether the sustainability promises made by consumer goods companies and packaging makers are mere greenwashing.

“Sachets are the most visible face of litter in any developing market,” admits Pradeep Banerjee, who heads the supply chain for Unilever’s Indian subsidiary. “But they are [a] very efficient means to get items of everyday use to remote areas of the country . . . if you have to transport one litre of a fluid, a plastic bottle would give 10 times the carbon footprint of a lighter sachet. It’s not going to be an easy nut to crack.”

If the sachet is among the hardest types of plastic packaging to which to apply a circular economy model, one of the easiest should be the plastic bottle, pumped out by the millions of tons a year by companies such as Coca-Cola, PepsiCo, and Danone. That is because it is standardised, made out of a simple material — PET — and has a resale value.

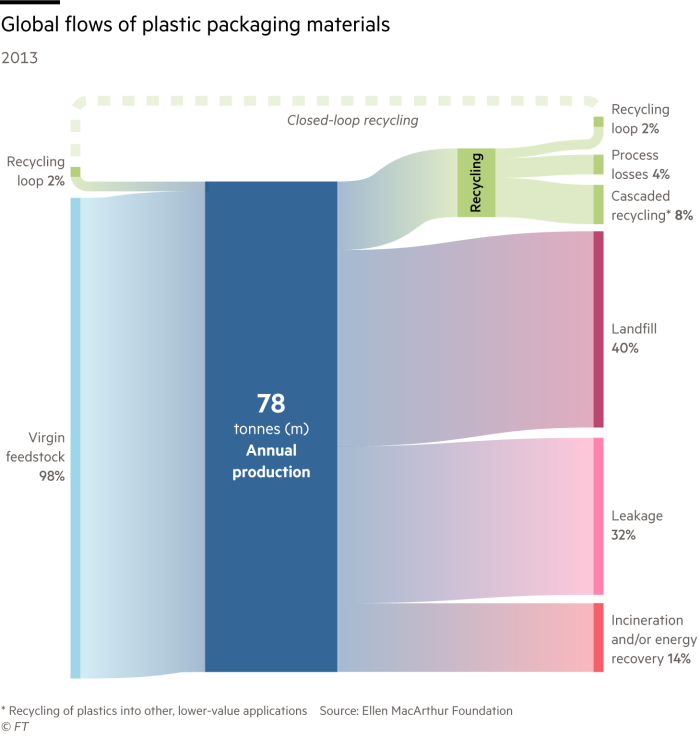

Although PET has a higher recycling rate than any other type of plastic, only 7 per cent of it is recycled into bottles — the rest is “down-cycled” into industrial uses in carpets or apparel. Globally, less than half of PET bottles are actually collected for recycling, according to the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, a non-profit that is leading a cross-industry project to promote a circular economy for plastics. That is better than the average, however: only 14 per cent of plastic packaging is collected for recycling globally, and the figure drops further when losses during sorting and reprocessing are factored in. In the end, only about 5 per cent of the value of plastic packaging is retained for subsequent use.

In contrast, the global recycling rate for paper stands at 58 per cent, while that for iron and steel is between 70 and 90 per cent.

It is a far cry from the vision of a true circular economy for plastics. But Sander Defruyt, who heads the Ellen MacArthur New Plastics Economy project, which began four years ago, says he sees signs that change is afoot. About 400 consumer goods makers, packaging producers, retailers, and recycling companies have signed up to voluntary commitments to spur more recycling, reuse and reduction of plastic through to 2025. “We started by bringing the whole value chain together,” he says. “There is a lot of preparative work happening behind the scenes.”

New technologies known as chemical recycling may offer solutions if their cost can be brought down. Unlike traditional mechanical recycling, which grinds plastic into pieces that can be used to make new items — which is what Green Antz does — chemical recycling breaks plastics down into their constituent polymers. This overcomes many of the shortcomings of traditional recycling, where the material that results is not as clear or as strong as virgin plastic.

Small companies such as Carbios of France and Loop Industries of Canada are working on these techniques, as are big businesses including Unilever and Nestlé. Some are collaborating: the chemicals giant Dow will use a new technique developed by Dutch company Fuenix Ecogy Group to “crack” plastic into a form that can be used in a fresh round of manufacturing. Jeff Wooster, Dow’s global sustainability director, says the partnership shows how things are changing in the industry.

“Today we only have a small offering of products that are made of recycled content, but we are serious about expanding it and making this a real business,” he says. “Dow’s end goal is to transform our business model to be in line with circular economy principles, as many companies are trying to do.”

They will have their work cut out. While Mr Defruyt of the Ellen MacArthur Foundation insists that substantial change must be achieved in the next few years, he acknowledges the scale of the task. “There is no real handbook for how to change a global industry,” he says.

Comments