Eurozone leaders are pushing the ECB into murky waters

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The writer is founder of Dezernat Zukunft, a macrofinance think-tank

As the European Central Bank prepares to launch a critical new tool to tackle the threat of fragmentation of the eurozone’s financial markets, governments still seem to be sitting on the sidelines.

That is a mistake. It is pushing the central bank into murky political territory, risking its credibility and may result in another lost decade marked by under-investment, stagnation and growing economic divergence between member states.

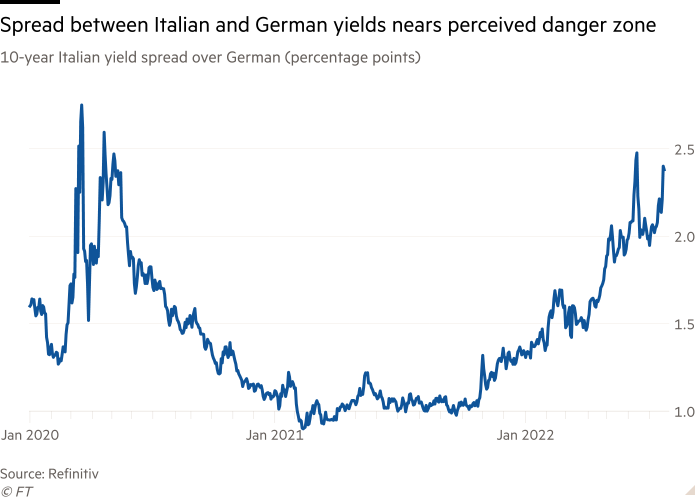

The ECB’s bond-buying mechanism to be outlined on Thursday aims to address the gap between the yields on German and other government bonds in the eurozone. Such spreads can cause an uneven transmission of monetary policy.

Assume for instance that the ECB raises rates by 0.25 percentage points and that this causes the spreads between German and Italian government bonds to increase from 1.5 to 2 points. Since government bonds act as benchmarks for credit pricing, high spreads would lead to a tighter monetary policy stance for Italian borrowers.

With spreads unaddressed, conducting monetary policy would lead to inflationary outcomes in Germany and deflationary ones in Italy. This is undesirable from a monetary policy perspective and works against convergence in the eurozone.

Now switch perspective to fiscal policy. For fiscal policy, ECB bond purchases have two effects: one is secure access to credit for the respective governments and, two, a lower than otherwise cost of borrowing. The latter has a direct impact on compliance with European fiscal rules: lower interest payments mean more space under the 3 per cent deficit limit.

The current institutional set-up thus muddies the waters: to pursue its mandate, the ECB must address spreads. But addressing spreads has fiscal consequences. In particular, in addressing spreads, the ECB effectively decides which member states benefit from the privilege of sovereign borrowing, under what conditions and at which price. That is a deeply political issue, on which a technocratic, non-elected body is ill-suited to pronounce.

The ECB can only make choices within this ambiguous architecture; and while some are worse than others, none are good. Governments on the other hand could unmuddy things — and should. It is they who are currently deferring deeply political issues around sovereign debt to the ECB. It is they who should decide which country has sound government finances with a collective judgment.

Where member state governments decide a country runs sound fiscal policy, the ECB could pursue its mandate without stepping into fiscal territory. Where they decide it has not, it is clear who made that judgment and why, and who is accountable for its consequences.

In this case, spreads could only be addressed through the Outright Monetary Transactions programme that was launched during the 2012 debt crisis. This involves the ECB buying a country’s sovereign debt in the secondary markets — as long as that country has agreed to a rescue package from the European Stability Mechanism and tough reform requirements.

Addressing spreads is in governments’ self-interest: the higher spreads are, the more difficult it will be to marry the goal of reducing debt ratios with sustaining high levels of investment. Rising interest payments leave less money for public investment. Increasing financing costs reduce the number of profitable private investments.

Hence governments should have no interest in maintaining spreads — except as disciplining devices addressing specific misbehaviour, a function they could still serve if the use of the fragmentation tool were conditional on sound government finances.

A criterion that governments could use to assess fiscal policy could be the primary balance — the difference between the amount of revenue a government collects and the amount it spends excluding financing costs. By definition, the primary balance is not influenced by monetary policy. Thus, a country could, for instance, get its peers’ stamp of approval if it runs a primary balance likely leading to debt reduction.

Governments have been keen to emphasise the flexibility of the Stability and Growth Pact as an asset. Flexibility is supposed to ensure that countries are not tied up in an overly restrictive corset of fiscal rules unfit for their respective circumstances. That sounds good in theory. Yet, in practice, strategic ambiguity on the side of fiscal policymakers implies that the ECB is left with political choices — ones it did not have to take if governments played their proper part.

Comments