Food for the boys

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

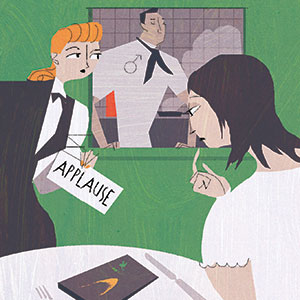

In March this year writer and critic Alan Richman used his column in the US magazine GQ to deliver a ravening polemic on the state of the American restaurant scene. There is, he says, a new and pervasive kind of cuisine, and he lists its characteristics: obscure, often foraged ingredients, weird combinations, tiny portions, tableside “narrative” from the server, tasting menus, it is simultaneously “intellectual … yet often thoughtless” but, above all, it centres on the chef, whose ideas, creativity and personality it’s all about. “The job of the customer is to eat what’s placed before him, and then applaud.” And because there’s no name for this trend yet, he handily coins one, “Egotarian Cuisine”.

God, it’s good. I wish I’d written it. It ties up all the irritants of modern dining into one neat package and then punts it neatly into a bin. But hidden halfway through, almost as an afterthought, is a single paragraph that in many ways is far more provocative.

“I came upon this kind of cooking again and again. It’s not limited to New York or California, where indulgences tend to thrive. Something else you should know is that it’s entirely male. I found no exceptions. Not once have I seen a female chef prepare such food.”

Surely, I thought, that can’t be true, not in the UK at least, but as it happened, last week I got a chance to test it. I’d been invited to host a series of three discussions on women in food. The organisers had assembled an amazing set of panellists, chefs, writers, producers and food entrepreneurs and the packed audiences comprised a good cross section of the female reading, eating, cooking, consuming and thinking public. Each night I read out Richman’s assertion and each night, the reaction was similar.

“Well yes! Obviously,” was one of the repeatable responses. Sometimes followed by “ … and you’re remotely surprised?” or on other occasions with a sort of weary and indulgent chuckle.

I could not find, among panel or audience, anyone who would disagree that the kind of cooking we’ve grown to accept as the cutting edge of our national cuisine was anything other than an elaborate competition between idiotic boys. Nobody actually used the term “pissing contest” but that was solely because they were too polite.

It was shocking. I’m immensely proud of the way this country has recovered and developed a food culture, proud of our chefs, our writers, critics. We’ve bounced back after generations of neglect to have a restaurant scene that’s the envy of the world, a nation seemingly hanging on every word of a cadre of internationally recognisable celebrity culinary superstars, and yet for at least half the population it’s obviously either irrelevant or indulged with a polite chuckle as the sort of behaviour you might observe among sexually immature male primates.

There are many generalisations made about male and female approaches to cooking. Professional cooking was long a male preserve because of the physical demands. Women tended to head private or institutional kitchens while men led restaurant “brigades”. Doubtless there is a Frenchman somewhere on the Rive Gauche with a roll-neck sweater and important hair who will opine that men transform food in the pan by main force, fire and tools while women incubate and nurture in the uterine spaces of pot and oven. Men kill, cut and sear; women gather, combine, ferment and culture. These are all entertaining to debate at the tail end of a good meal – an interesting enough idea to start an argument, but far too woolly to finish one – but what Richman touched on, and what those rooms full of women in food confirmed to me is a deeper and more worrying trend.

Modern cuisine was supposed to be about shaking up the old rules. It’s the defining pretension of the snake-hipped young chef that he’s not bound by the old prejudices. He isn’t held back by traditional techniques, he scorns the classical European canon. His food transcends limitations of nationality as he fearlessly “fuses” global cuisine. He subverts restrictions of class as he bravely reappropriates food of poverty and cleverly explores the “soul” of cheap and forgotten dishes. He is entirely the New Man and the Wonder of the Age – but he ignores a chasmic and growing gender divide.

Call it “Egotarian” or just profoundly boyish but this cuisine has become the norm for aspiring young male chefs and ambitious cooks of the MasterChef generation. I realise, of course, that this may be a pendulum swing, a reaction against the “female”, nurturing, peasanty cuisine of the Shaun Hill, Fergus Henderson, Alice Waters and River Café cohort, but surely the fact that half of food lovers greet modern cooking with a collective “so what?” is enough evidence that it’s time to get in touch with our female side again.

Tim Hayward is an FT Weekend contributing writer and winner of the Fortnum & Mason and Guild of Food Writers’ awards for food writer of the year.

tim.hayward@ft.com; Twitter @TimHayward

Illustration by Richard Allen

Comments