More choice means higher prices for American diabetics

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

When Baqsimi came on to the US market last year, some parents of young diabetics breathed a sigh of relief. The nasal spray made it far easier to treat severe hypoglycaemic attacks, replacing a kit that required those in the vicinity of the incapacitated patient to administer injections, even if they had never done it before.

Julie Settles, director of medical affairs at Eli Lilly, the pharmaceutical company behind Baqsimi, says the product made her feel “warm and fuzzy” from the moment she heard about it. The Indiana-based drugmaker bought the drug from Locemia Solutions in 2015. Robert Oringer, Locemia’s co-founder, had spotted the problem with the existing solutions while taking care of his own diabetic children.

Now more parents feel confident that their children’s friends could administer it: a study on a mannequin showed that about 90 per cent could use it without training, compared with 15 per cent using the injectable with training.

The product is one of a number of recent pharmaceutical innovations that promise to make life easier for diabetics. Yet affordability in the US remains a serious problem: despite the growing number of products, prices have risen sharply, with even insulin becoming unaffordable for some patients.

Unlike many countries, the US imposes no price controls on medicines, an anomaly that has made healthcare a big issue in this year’s presidential election. Drug manufacturers, meanwhile, argue that high prices are essential if they are to carry out innovative research and development.

Novo Nordisk’s Rybelsus, which is aimed at type-2 diabetics, is the first glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) treatment in a pill; GLP-1 is a hormone that helps to regulate blood sugar.

Todd Hobbs, vice-president and diabetes chief medical officer at Novo Nordisk in North America, says the drug took “decades of research”. “In a nutshell, the hard part is that insulin and GLP-1 proteins are large proteins that your stomach is designed to break down,” he says. “It has been one step forward, two steps back, as we try to find a way for it to be absorbed enough in the stomach and gut to have an effect helping patients with diabetes.”

One benefit to many of the diabetes drugs released over the past few years is that they also address cardiac problems. Rybelsus contains the same active ingredient — semaglutide — as Novo Nordisk’s Ozempic, an injectable, which is also approved by the Food and Drug Administration to reduce the risk of cardiac events, including heart attacks.

Robert Eckel, president of the American Diabetes Association, says there is an “increasing recognition” that doctors should try to treat diabetes and cardiac problems simultaneously, because diabetics typically die of cardiovascular disease.

“These drugs have grown so much in popularity because they can treat the heart, the kidney, and reduce hospitalisation,” he says. “But they are not as well covered [by insurance] as we would like and copays [paid by patients] remain high. The cost of these agents [is] not cheap when the patient has to pay for it him or herself.”

The price of insulin has soared in recent years, which means that patients without insurance or with plans that expect them to pay the first few thousand dollars, struggle to afford the hormone, which is essential for type-1 diabetics and needed by some type-2 patients.

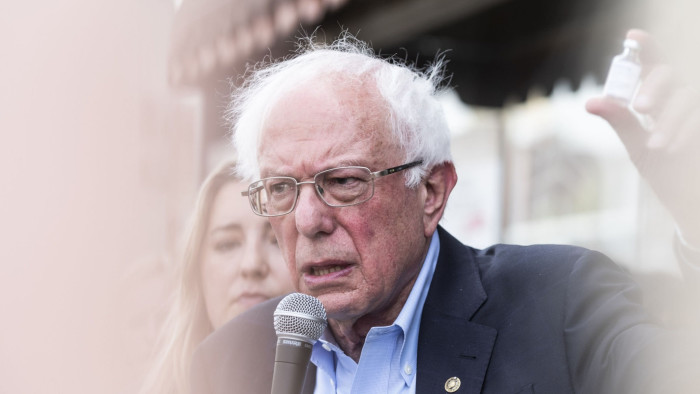

Insulin prices have become a campaign issue for presidential candidates including Bernie Sanders, after reports of people dying because they rationed their own essential treatment. Insulin makers Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk and Sanofi have all developed assistance programmes for poorer patients or cheaper versions of the product to try to help diabetics and to address the public criticism.

The price of branded diabetes drugs has also soared in the past five years, up 40-50 per cent since 2015, according to data from research firm Elsevier.

Podcast: How to Build a Healthy City

FT correspondents unearth the ways cities are helping their citizens live healthier lives, from doctors who prescribe exercise rather than pills, to a car-free economy that is booming. Listen to the series

Michael Rea, chief executive of Rx Savings Solutions, which makes software to help employers lower the drug bills arising from their health insurance plans, says many diabetics struggling with insulin costs are carrying “a heavier financial and emotional burden each year”.

“There is an unchecked market dynamic that pushes drug pricing boundaries in to unreachable territory for more and more patients each year,” he says.

Pharmacy benefit managers, who act as middlemen between drugmakers and insurers, expect larger rebates because there are so many drugs in the category. They require rebates as an incentive to put a drug on the formulary of what is paid for by insurance — or to put it higher up the list so a patient can access it quicker. For patients with good insurance, the list price often does not matter, but that is not the case for everyone.

Anna Kaltenboeck, programme director at the Center for Health Policy and Outcomes and the Drug Pricing Lab at Memorial Sloan Kettering, says the entire class of drugs known as GLP-1 receptor agonists (such as semaglutide) and SGLT-2 (sodium-glucose co-transporter-2) inhibitors is getting “overpriced”. As a consequence, patients take less of drugs they need.

“People ration. They ration based on price. They use less insulin when they should use it and other drugs,” she says. “Studies have shown that adherence tends to alter with high out-of-pocket costs.”

Of adults prescribed a diabetes medication, 13.2 per cent skipped doses or delayed filing a prescription, and 24.4 per cent asked their doctor for a lower-cost alternative, according to a 2019 survey by the National Center for Health Statistics, based on the previous 12 months.

Joyce Kadam, a 63-year-old diabetes patient from Maryland, is struggling to afford her Jardiance, an SGLT-2 made by Boehringer Ingelheim and Eli Lilly, on top of the other medications that she and her husband need.

At the moment, it costs her $80 to $85 a month, but she expects this bill will increase to hundreds of dollars when her husband loses his insurance in the summer. Then, she thinks she will have to ask the doctor for a sample of the drug, often given out by sales representatives, or to prescribe a cheaper alternative.

“Otherwise we might have to think twice. I want to take it because I don’t want to have a stroke like my mother-in-law did,” she says. “I have, you know, the car, the bills, the mortgage . . . I wonder sometimes what will happen next.”

This article has been amended since first publication to reflect the fact that Eli Lilly is based in Indiana

Comments