Let’s solve the learning crisis together

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The writer is executive director of East African civil society organisation Uwezo Uganda, and writes on behalf of nine organisations that form part of the RISE Community of Practice, a group of education practitioners

As UK prime minister Boris Johnson and Kenyan president Uhuru Kenyatta prepare to host this week’s Education Summit in London, and seek ways to improve the prospects of children around the world, they should heed five lessons on tackling the global learning crisis.

First, we commend the leaders for drawing attention to the issue. Solving the learning crisis is critical to addressing the world’s development priorities. Even before the pandemic, millions of children had been left behind. A staggering 90 per cent of 10-year-olds in low-income countries are unable to read and understand a simple text. Most are in school but learning little. Even in middle-income nations, many are failing to learn. In South Africa, 78 per cent do not learn to read for meaning in the first three years of school.

It is imperative that politicians see education as a mechanism to solve complex global problems. Without learning, children are condemned to a life of poverty and scarcity, and their countries face a cycle of limited economic, health and social growth. Those who learn contribute to development. Improved girls’ education, for example, reduces teen pregnancy, and infant and maternal mortality.

Second, “business as usual” will not be enough. More funding is needed to get children learning, but we cannot continue to repeat the same things as in the past and expect a different result. Recent research reveals that huge amounts of donor money have been spent to increase the number of children who can access school — but without significant benefit to learning.

Attending school without learning is a miserable experience and leads to dropout. In Uganda, for example, an estimated 240,000 pupils who enrol in primary school quit before their fourth year. This is catastrophic for their country’s future economy, social welfare, health and even democracy.

Getting more girls — or boys — into school without improving quality will merely cause more frustration. The money raised through the replenishment of the Global Partnership for Education (GPE) — the international fund dedicated to transforming education in lower-income countries — needs to be invested specifically in approaches that support learning.

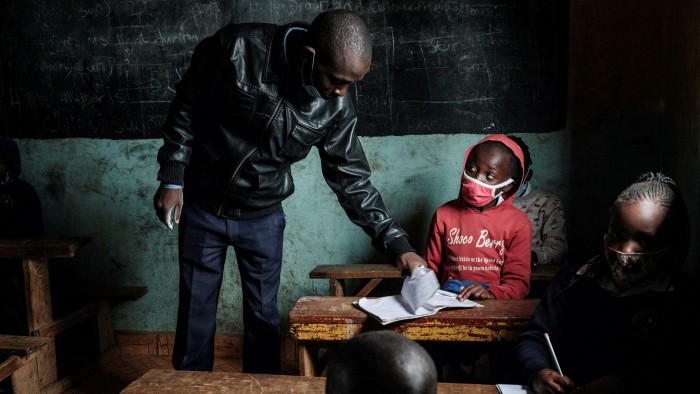

Third, focus on foundational skills. In countries where the majority of children are not achieving even basic literacy and numeracy, we need to concentrate on simple reading and maths, taught in accessible ways. Acquiring these skills is a prerequisite for further, higher-order learning that can help children fulfil their potential. Many have fallen further behind because of Covid-related school closures, so supporting them to catch up should be prioritised.

To avoid wasting resources, there is also an urgent need to measure children’s learning levels. This will help tailor teaching and inform policymakers. Learning data, gathered by independent institutions not subject to political interference, should be studied before any further funding is disbursed. Countries must commit to ensuring all children can read and do basic maths by age 10 — and ensure there is a simple and verifiable way to track progress.

No education system is stronger than its teachers or school leaders, who deserve the coaching and flexibility needed to help their children succeed. The burden of measurement and teaching at the appropriate level falls mainly on them. Funders should focus on their recruitment, training and continuous upskilling. Promising models include the Catch-up Program in Zambia, which resulted in significant improvements in basic literacy and maths.

Fourth, treat the root causes rather than be tempted by “silver bullet” solutions. If education systems are set up to drive access rather than learning outcomes, then “surface level” interventions will be counterproductive. For example, in India, an expensive intervention to promote “best practice” in school management had no impact on learning because the system rewarded access rather than learning.

It can be tempting to invest in highly visible infrastructure projects, but better results will come from efforts to improve learning, whatever the nature of the school. An expensive classroom has never helped as much as a well-trained, motivated teacher and a child who is ready for school. Furthermore, spending on buildings often results in corruption and procurement fraud.

Computers, connectivity and other high-tech solutions may appeal to donors as a way to “leapfrog” progress. But the preconditions for them to be effective are not present in the places with the biggest need. Such approaches are usually ineffective and divert money from interventions that work best to get children learning.

Finally, build partnerships. The network of organisations I represent is one of many ready to share knowledge and work closely with governments. It takes a village to educate a child and we urge political leaders to engage with civil society, teachers, academics, researchers and communities. We need both to raise awareness of the magnitude of the crisis and to energise a strong coalition to take the action needed to get all children learning.

Comments