Climate graphic of the week: When heat records fall

Simply sign up to the Climate change myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

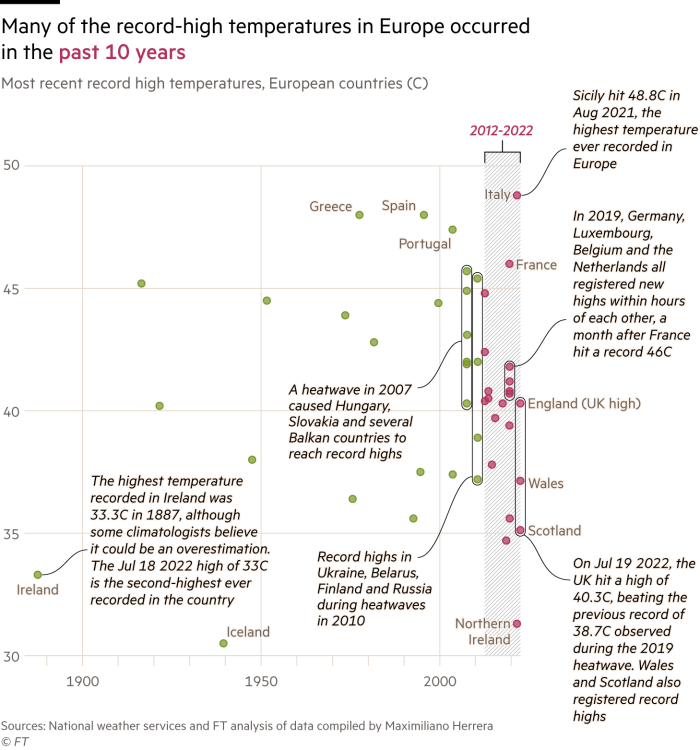

The UN designation of the past decade as the hottest on record has been underscored by the latest heatwaves, with more than 40 per cent of the peak temperatures in Europe falling in the period since 2012.

Scientists are clear that climate change will drive more frequent and intense weather extremes, with the landmark UN report signed off by 270 scientists from 67 countries earlier this year concluding that the risks associated even with lower levels of global warming are greater than previously thought.

The planet has already warmed by at least 1.1C since pre-industrial times due to human activity, and is projected to keep warming for some time even if greenhouse gas emissions are rapidly curbed.

Out of 47 all-time national highs in Europe that have been documented, 21 have occurred in the years since 2012, according to FT analysis, including new records for England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland.

The highest temperature recorded on the continent was 48.8C in Siracusa, Italy, in August 2021. The only other nations in the bloc to have hit 48C are Greece and Spain, according to the data compiled by climatologist and weather historian Maximiliano Herrera.

Jonathan Porter, chief meteorologist at the US commercial forecaster AccuWeather, said the European heatwave in July “will go down in the record books as a truly historic event — one of the most extreme and impactful heatwaves in Europe.”

The UK record of 40.3C reached last week was notable for two reasons, Stephen Belcher, chief scientist at the UK’s Met Office, has said. The first was that the record was broken by a full 1.5C, when it had previously been by fractions of a degree.

Second, the very high temperatures were experienced over a large area: “That was a surprise . . . to get such a big area breaking records,” he told the BBC. Without climate change, temperatures of more than 40C would have been “virtually impossible,” Belcher said.

As wildfires tore through parts of France, Spain and Portugal, Copernicus, the EU’s Earth monitoring programme, said that large parts of western Europe continued to face an “extreme” and “very extreme” risk of fire.

The total estimated carbon emissions resulting from the fires in Spain alone during June and July were the highest for the period recorded since the data began to be collected in 2003, Copernicus said.

Globally, last year was the fifth warmest on record, according to Copernicus, and the first six months of 2022 rank as the sixth-hottest January to June period, according to the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Historical temperature records remain contentious, however, coming under scrutiny from the modern meteorological community. Concerns over instrumentation, location and observer reliability are among methodological issues cited by experts reviewing the information.

Europe’s oldest heat record is held by Ireland at 33.3C, documented at Kilkenny Castle in 1887, has been questioned by climatologists but the national weather service has stood by it. That would place the past week’s high of 33C as the second-highest temperature on record for Ireland.

Despite the questioning of some pre-industrial records, commonly accepted national records in the past century reveal a clear pattern of climate change.

Climate Capital

Where climate change meets business, markets and politics. Explore the FT’s coverage here.

Are you curious about the FT’s environmental sustainability commitments? Find out more about our science-based targets here

Comments