David Gardner, FT journalist, 1952-2022

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

David Gardner, former international affairs editor, Middle East editor and chief leader writer of the Financial Times, who has died suddenly in Dubai at the age of 69, was one of the outstanding international correspondents and commentators of his generation. He also wrote like an angel.

He combined a conviction of the importance of understanding history with a fascination for political intrigue, an impatience with humbug, a love of telling stories, a passion for good causes, a detestation of dictators and an irrepressible sense of humour. His lucid prose made the most complex subjects, from Middle East politics to the European Common Agricultural Policy, easily intelligible to the uninitiated. In the words of Roula Khalaf, FT editor, he managed to combine the best writing on the paper with “passion and integrity”.

Born in Brussels, where his father was a British diplomat (although Gardner always carried an Irish passport, thanks to his grandfather), he was sent to Stonyhurst, the British Catholic boarding school, where he was taught by Jesuit priests. The teaching marked him for life. “The Jesuits taught us a sense of human solidarity, and an openness to the world,” according to Jimmy Burns, a school contemporary and fellow FT correspondent. They also instilled an intellectual rigour and analytical capacity Gardner never lost.

He won a place at Oxford to read English, and found ample time to throw himself into leftwing causes. He found a common interest in Christian socialism and a spiritual mentor (Anglican priest Peter Thomson) with another very political contemporary: Tony Blair, the future Labour prime minister. “We spent many, many hours in intense political discussion and debate,” says Blair. “He was an extraordinarily reflective, deep-thinking person, always striving to get to the heart of an issue, always, whatever his feelings, seeking objective truth. I learnt a lot from him. It didn’t surprise me that he became a journalist.”

According to Burns, Gardner was always determined to work for the FT. Although the Middle East was to become his greatest passion, he began his 44-year career at the newspaper modestly enough in 1978, as a freelance “stringer” in the rebellious regions of Spain. He was sympathetic to their striving for autonomy, but never uncritical.

By 1980, he had made it on to the staff in London, as part of the team launching the FT’s international edition. But he was not a natural desk man. Within five years he had left again to become a “superstringer” in Mexico, where his reports of political corruption, and the increasingly bloody civil wars of Central America, demonstrated style, wit and a view of the story’s wider importance.

Gardner was already winning a reputation for the perceptiveness, courage and clarity of his reporting. His fate was to be sent to Brussels to cover agriculture. “He knew nothing about it when he arrived, but he made himself the greatest expert on milk quotas,” says Lionel Barber, former FT editor, who became Gardner’s bureau chief. “He almost took a delight in mastering all the detail and writing about it.”

One rival Brussels hack sought to exploit his success. Gardner used to tell how Boris Johnson, as Telegraph correspondent, had once copied whole paragraphs from his FT story the following day. “I accused him of blatant plagiarism,” Gardner said. The future prime minister was unashamed. “Don’t you know we treat the FT as a primary source,” he replied.

Gardner’s reputation opened the door to the job of FT Middle East editor. It was the perfect fit for someone who was passionate about ideas and people, a place of ancient history and a complex and conflicted present. “He had an intense and unwavering view of the region’s hard power realities, of the sweep of history,” says Andrew Gowers, who did the job himself before becoming FT editor. “In a region where media coverage can seem obsessed by the horrors of the moment or swayed by partisan feelings, David’s vision was unusually steady and his analysis unfailingly reliable.” He was both angry at the abuse of power by so many Arab autocrats, and the failure of Israeli democracy to produce a fairer solution for the Palestinians, and coolly analytical about the consequences.

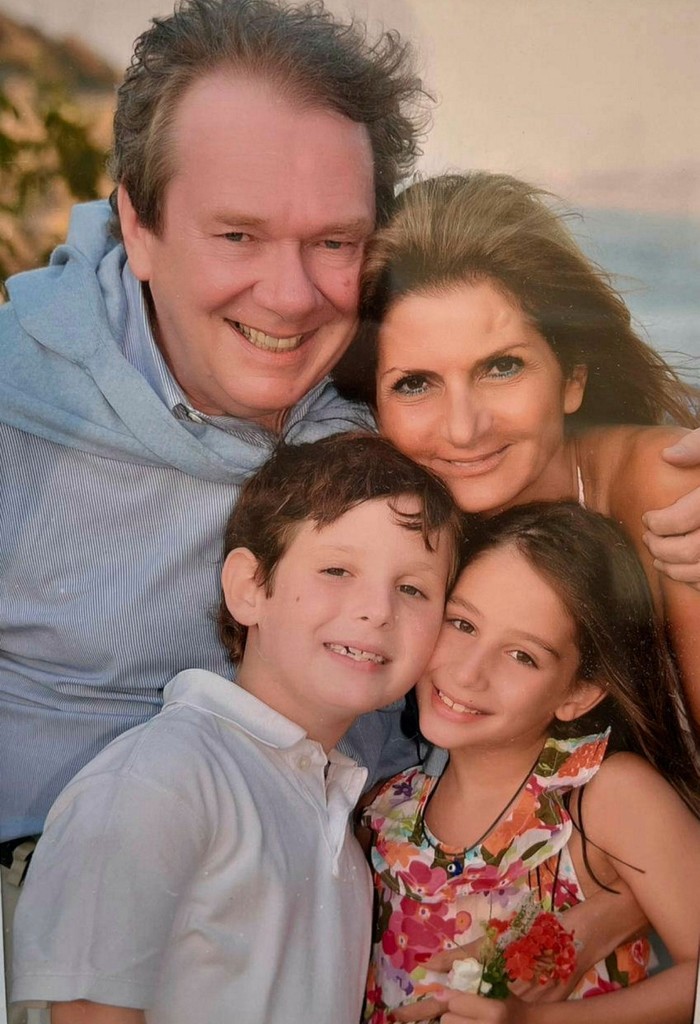

His passion and understanding were also influenced by Samia Nakhoul, his brilliant and much-loved second wife, Middle East editor for Reuters, who is mother to their twins Terence and Haya. They survive him, along with his daughter Daniella by a first marriage. The family moved from Beirut to Dubai after their apartment was wrecked in the port explosion in 2020.

In his book Last Chance: The Middle East in the Balance, Gardner summed up his view: “Unless the Arab countries and the broader Middle East can find a way out of this pit of autocracy, their people will be condemned to bleak lives of despair, humiliation and rage for a generation, adding fuel to a roaring fire in what is already the most combustible region in the world.

“It will be primarily up to the citizens of these countries to claw their way out of that pit. But the least they can expect from the west is not to keep stamping on their fingers.”

He wrote the book after the war in Iraq, which he had condemned as a disastrous blunder by the US and its allies, including his old friend Blair. What distressed him almost as much as the senseless bloodshed — in which Samia almost lost her life in a US missile attack — was the ignorance of history demonstrated by the western allies and their failure to appreciate the conflict they would aggravate across the region.

“We owe the FT’s opposition to the Iraq war almost entirely to his intellect and moral courage,” says Martin Wolf, FT chief economics commentator.

His colleagues remember a man who was kind and generous, as well as waspish and witty, a great mentor for young journalists, and quite capable of consuming alarming quantities of Spanish red Rioja before returning to the office to compose a passionate, perfectly written editorial. He will be greatly missed.

Comments