Europe First: how Brussels is retooling industrial policy

Simply sign up to the Electric vehicles myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

In a patch of woodland 100km west of Stockholm, an entirely new industry for Europe is taking shape. Inside a grey box structure hundreds of workers are rushing to complete the first big European-owned production line for battery cells to be used in electric vehicles, grid networks and many other areas.

With production due to begin by the end of the year, the Northvolt site in Vasteras, central Sweden, is buzzing with activity. But the yellow tape cordoning off certain areas bears the words “limit line” in English and Japanese — one indication that Northvolt has had to tap Asian expertise in research and development to build its facility.

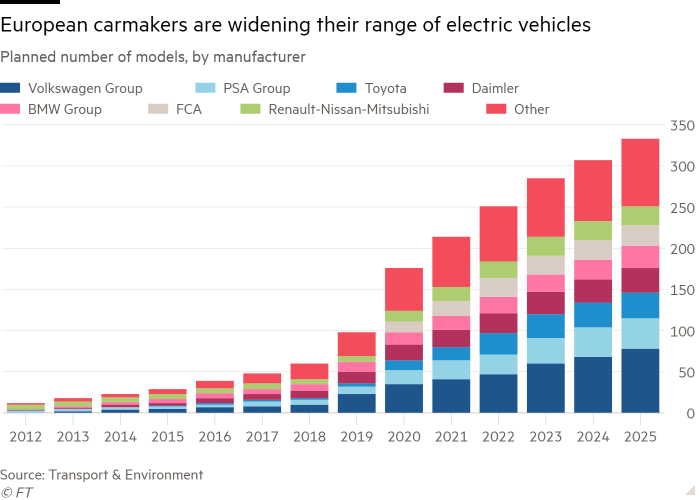

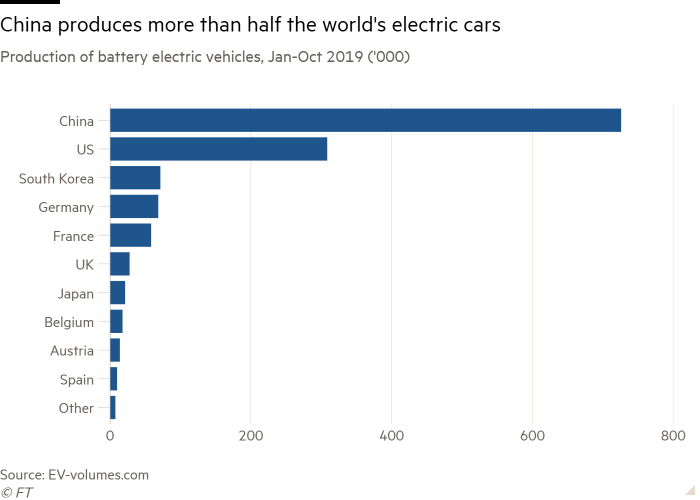

European carmakers were slow to respond to the electric vehicle revolution and are almost entirely dependent on imported battery cells. Global production is dominated by Japan’s Panasonic, South Korea’s Samsung and CATL and BYD of China. European factories account for only 3 per cent and they are mostly Asian-owned.

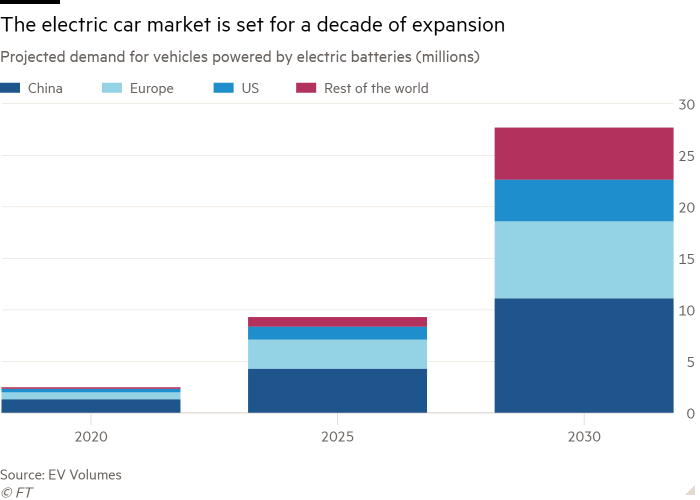

Yet According to EIT InnoEnergy, an EU-backed investment vehicle and research house, the potential value of the entire battery value chain in Europe – mining, refining, cell manufacturing, battery packs and recycling – could be €250bn in 2025. That has left EU policymakers and businesses scrambling to make sure European companies take a big slice of the action, and with it boost jobs and skills.

Flush with €1bn of funding from Volkswagen, Goldman Sachs and Ikea, Northvolt will launch its Vasteras plant as a dress rehearsal for its own, much larger gigafactory in Skelleftea, northern Sweden, where production should start in 2021.

“We knew there would be battery factories built in Europe,” says Peter Carlsson, a Swede who set up Northvolt with the idea of creating a European rival to Tesla, where he used to be a manager.

Europe First

This article is part of an FT series exploring Europe’s efforts to boost competitiveness as its companies are squeezed by the US and China.

Part one

How to build a national champion: the EU’s new industrial policy

Part two

Internationalising the euro

Part three

The greening of trade policy

Part four

The data on European industry

Follow the series at ft.com

“But would they be satellite factories of Asian manufacturers or a real European battery ecosystem? The choice has a really significant implication for the European economy, for jobs, for the automotive industry.”

The new battery factory is one of the first steps in a big shift in the way that Europe thinks about how to develop new industries as it tries to deal with competition from China and the US.

Mr Carlsson and his Northvolt venture are at the vanguard of an ambitious effort — one that would have been unthinkable a decade ago — to create an entire battery industry on European soil, owned by European companies. The initiative stretches from mining and refining the raw materials such as lithium to manufacturing and recycling batteries.

Governments, universities, EU institutions and scores of businesses, including the leading carmakers, have joined forces in a new industrial policy drive that could become a blueprint for many other technologies and sectors.

Fearing European industry could be crushed by US technological supremacy, Washington’s growing protectionism and Chinese state capitalism, German, French and EU leaders have embraced a reinvigorated industrial policy as a tool to assert the continent’s technological independence and ensure its economic survival.

Tesla’s recent announcement that it would build its own gigafactory to build cars and batteries near Berlin only adds to the pressure for Europe to get its act together. The news that Audi is to cut 9,500 jobs in Germany is a further reminder that the shift to EVs could hit an industry that has been a backbone of industrial employment in many European countries.

Together with efforts by the EU to ensure that other countries share the burden of carbon emissions reduction and a renewed drive to challenge the supremacy of the US dollar, it amounts to a bold attempt to put Europe’s economic interests first.

“I really think of this issue in terms of sovereignty,” says Bruno Le Maire, French finance minister. The auto industry is vital to Europe’s industrial base. But if it has to import batteries, which account for about 40 per cent of the cost of an electric vehicle, Europe risks losing the value-added part of the production chain and the technological knowhow that stems from it, he says. “Mobility is a matter of sovereignty.”

To its proponents, the combination of industrial collaboration, publicly funded research, transitory subsidies and global standard setting to encourage a large-scale European value chain is an intelligent reinterpretation of an old-fashioned industrial policy of state-directed investment.

“When you have learning going on through new technology you want to be part of it because it can spill over to new sectors,” says Dalia Marin, professor of economics at Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich. “It is knowledge creation for the whole economy.”

A few years ago, this approach was out of fashion in Europe. While France and some other states have always advocated an active role for government in supporting industry, the EU was more concerned with building open, competitive markets with strict controls on public subsidies. But US technological supremacy and Chinese advances have forced a rethink.

“When we started this in 2016, we saw a fairly big difference between how China approached this and how Europe did,” says Mr Carlsson, in a corridor of Northvolt’s makeshift office in Vasteras. “In China, they are financing companies, helping the build-up of the industry but also developing the market for electric vehicles. Europe is starting to catch up now.”

A turning point was the creation in 2017 of the European Battery Alliance, a group comprising EU policymakers and scores of companies with the aim of creating an innovative and competitive “ecosystem” for batteries in Europe.

“We discovered two years ago an assumption in the motor industry that the shift to EVs would come much later and that batteries would be a commodity,” says Maros Sefcovic, the EU’s outgoing energy commissioner, who spearheaded the EBA. The industry’s complacency spurred the commission to intervene and declare batteries a “strategic value chain”. The EU had learned the lesson of solar power, a technology it invested heavily in — only to see Chinese companies dominate mass production partly because of much tougher EU environmental standards.

The challenge was to persuade carmakers that nascent European suppliers could massively scale up production while in turn reassuring battery makers that the carmakers would become long-term buyers. “We needed to use the convening power of the European Commission to get the right people in the room,” Mr Sefcovic says.

Northvolt was one of the first beneficiaries of the EBA initiative. When it announced in 2017 that it would build a $4bn plant close to the Arctic Circle — a long way from Europe’s main car assembly plants but close to plentiful and cheap hydropower — investors and customers were sceptical.

“Nobody wanted to be the one standing in the corner if it failed,” says Mr Carlsson. “We worked at systematically moving the stakeholders forward step by step,” he says.

One by one, the company secured the backing of partners, including truckmaker Scania, engineering group ABB and wind turbine maker Vestas.

Northvolt borrowed €52.5m in cheap loans from the European Investment Bank in 2018 for its Vasteras project, then raised €350m for Skelleftea from the same source a year later. “The first steps are hardest,” Mr Carlsson says.

The Vasteras demonstration facility may be small, with a production of about 350 megawatt hours of batteries per year, but Northvolt’s Skelleftea plant is expected to have up to 40 gigawatt hours of capacity by 2024, bigger than Tesla’s gigafactory in Nevada. That equates to about 2bn individual battery cells, or enough for about 500,000-600,000 electric vehicles a year. The plant’s energy costs are about a quarter to one-third of China’s because of the cheap supply of hydropower.

Northvolt has also agreed a joint venture with VW for a factory in Salzgitter in northern Germany of up to 24 GWh. Mr Carlsson says the company’s eventual ambition is to have about 150 GWh of capacity by 2030, almost triple its current plans.

Northvolt’s Skelleftea plant will be the first large-scale homegrown producer in Europe but for EU policymakers it is just the beginning.

The EBA has helped to channel €100bn of announced public and private investment into cell manufacturing in Europe, according to InnoEnergy, and is aiming for the construction of up to 25 gigafactories in the EU.

European battery cell manufacturing is expected to grow tenfold by 2023, outstripping US capacity, according to Bloomberg New Energy Finance.

The French and German governments are pouring taxpayers’ money into two EU battery consortiums. The first, a French-led effort involving seven EU member states and 17 companies, is seeking Brussels’ approval for €1bn of state aid. A second, German-led venture will follow. Both are being organised as Important Projects of Common European Interest, an EU-sanctioned regime that allows exemptions from normal EU state aid and competition rules for multinational projects deemed strategically important.

Brussels adopted a similar policy for microelectronics and connected devices last year, approving €1.75bn of state aid. It has an older scheme for high-performance computing. After batteries, the commission is looking to adopt the same approach to a host of other technologies, including hydrogen technology, decarbonising heavy industry, autonomous cars, smart health and cyber security.

“I am convinced that our industrial strategy should mobilise the EU toolbox to support the development of key value chains and technologies that are of strategic importance for Europe,” Margrethe Vestager, the EU’s competition commissioner, told the European Parliament in October — comments that reflect the big change in European policy this year.

“These should be based on objective criteria — ie, because they contribute to technological sovereignty or because of their enabling character for a wide range of industries in Europe.”

On batteries, the focus is on the entire production cycle. Mr Sefcovic says Brussels has identified mining projects in 10 EU countries that could potentially allow the bloc to account for about 30 per cent of lithium production by 2030. But Europe currently has no lithium refining capacity, according to the commission.

It is also aiming for an overhaul of regulation for batteries by 2023, with new environmental standards for mineral extraction and cell production, software standards (for example, so that all batteries are able to pump power back into electricity grids) and recycling. It will give the EU a chance to shape the global market according to its own norms, potentially forcing Chinese manufacturers to follow tougher environmental standards.

Not everyone is happy with the EU’s embrace of interventionism. When German economy minister Peter Altmaier earlier this year espoused an active industrial policy, including the creation of European champions — tipping the EU debate firmly in France’s direction — it triggered strong criticism in German conservative economic circles.

Jeromin Zettelmeyer, a former senior German official, said at the time that Mr Altmaier’s push for “closed value chains”, reshoring all stages of production in Europe, was a “Trumpian feature” that would increase inefficiency and harm competitiveness.

“That is where the alarm bells are ringing quite loudly right now,” says Fredrik Erixon, director of ECIPE, a free-market think-tank in Brussels. “It has to do with the general perception, so far stronger in America than Europe, that size is key for competitiveness and that there is a trade-off between high levels of concentration and maintaining competitive markets.”

Mr Erixon says that while he had no objection in principle to the batteries consortiums idea, there was a risk that “the process of stitching together a compromise between so many countries and so many companies ends up with an outcome that nobody wants”. It could become the proverbial “camel that is a horse designed by a committee”.

But such are the concerns across Europe about intensifying technological competition from the US and China that there is barely a government that has not warmed to the idea of its own industrial policy.

Mr Le Maire, the French finance minister, says: “We have been able in less than one year to build a new industry in Europe. The example of batteries shows that when we have strong direction, determination and a public-private partnership, we can do it.”

At Northvolt, Mr Carlsson is in a race against time. The batteries from the first phase of production at Skelleftea have already sold out even though the facility will not come online for another two years. The company is growing so fast that he frets about potential bottlenecks for raw materials given the expected explosion in demand.

“The challenge is that in this industry there is no middle way: you need to go big to reach scale and have a chance,” he says. “There’s a certain risk . . . [But] right now, it’s all about execution.”

Comments