Curator June Givanni on African cinema: ‘Films need to be seen in their own countries’

Simply sign up to the Film myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

PerAnkh, an “Egyptian term for a place of learning and memory”, is how June Givanni sees her personal archive, now one of the world’s most important collections documenting the moving image for the African continent and its diaspora. Based in central London’s MayDay Rooms, dedicated to “history from below”, the June Givanni Pan African Cinema Archive ranges from rare videos and audio interviews to film and festival posters, screenplays and transcripts, snapshots and stills. It forms an alternative history of the past six decades of film-making with Africa at its heart.

I found its director, in silver earrings and black head wrap, preparing for PerAnkh, an exhibition on the collection that opens next month at Raven Row arts centre in Spitalfields, London. A precursor, Movements, curated by the artist Sonia Boyce, was shown at Chelsea College of Arts in 2014.

Amassed over 40 years (Givanni is 72), the pre-digital archive grew as a byproduct — and tool — of her career as a film curator. In 1983, she co-ordinated Third Eye in London, a film festival inspired by Third Cinema, Latin America’s challenge to both Hollywood and European art house. She has since programmed African film for TV channels and festivals from Martinique to Kerala, as posters on these walls testify. There are copies of the British Film Institute’s Black Film Bulletin, which she co-edited in the 1990s as founding director of the BFI’s African Caribbean Unit. Her special jury prize in 2020 from the British Independent Film Awards was, as one juror said, for an “extraordinary, selfless and life-long contribution to documenting a pivotal period of film history”.

Givanni’s unpaid work is supported by volunteers. A Freelands Foundation grant of £93,000 over two years was the “first funding of consequence” for the archive, which she insists is a collective endeavour, naming, among other collaborators, the director Imruh Bakari and academic Emma Sandon.

Holdings include early critiques, by scholars such as Stuart Hall and Jim Pines, of how black people and the African continent were misrepresented on screen. Givanni, born in British Guiana, was sent for in 1957 by her mother, a Red Cross nurse recruited to London four years earlier to help staff the NHS (June’s father remained in the Caribbean). “I was seven, at school since I was three. But they put me with five-year-olds.” That early shock at “who they think you are, and where they think you’re from — the ignorance astounded me” fuelled a growing interest in the corrective power of cinema.

Africa was then “always seen as a poor, backward, disaster-ridden continent that had little to offer to the world. But people knew nothing about the culture.” Her first visit to the continent in 1985 was for the Festival Panafricain du Cinéma d’Ouagadougou (Fespaco), a biennial beacon in Burkina Faso for pan-African cinema. The country’s president Thomas Sankara was, until his assassination in 1987, a “great lover of cinema. He would have lunch with 12 film-makers each day of the festival.”

Among the luminaries she met was Ousmane Sembène, the late Senegalese novelist and director whose centenary was marked at last month’s Fespaco. Borom Sarret (1963), following a cart driver through segregated Dakar, was the region’s first film by a sub-Saharan African. Black Girl (1966), sparked by the suicide of a Senegalese maid on the French Riviera, was its first full-length feature. Sembène, who once told me his influences ranged from De Sica’s Bicycle Thieves and Eisenstein to the African trickster figure, saw cinema as night school, and film-makers as modern griots. What struck Givanni was “how sophisticated and eloquent his early films were”.

Other nascent legends, including Med Hondo, Haile Gerima and Lionel Ngakane, “came with agendas they were determining themselves. They primarily spoke to the continent — which is where their integrity comes from.” Yet the Organisation of African Unity “recognised the diaspora as one of its regions”, Givanni says, and today’s now-feted generation of black British film-makers — John Akomfrah of Black Audio Film Collective, Isaac Julien, Steve McQueen and producer Nadine Marsh-Edwards — were “inspired by African film-makers”.

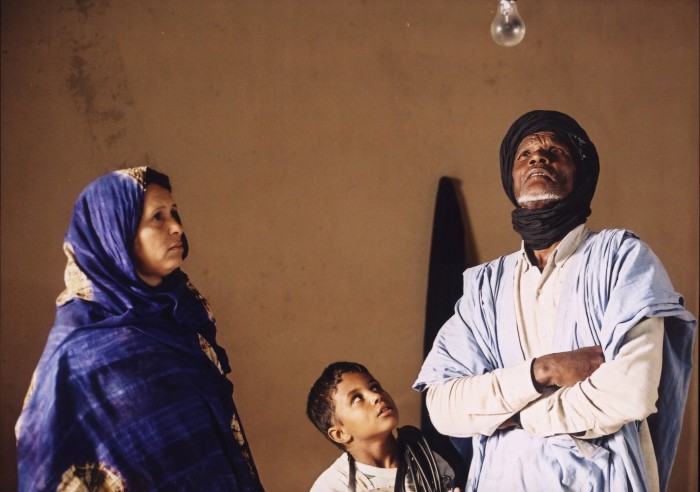

Francophone west African cinema had a head start from the 1960s, and a season at the Garden Cinema, in London’s Covent Garden, includes masterpieces by Sembène, Djibril Diop Mambéty (pictured at the top is his 1992 film ‘Hyènes’, or ‘Hyenas’), Souleymane Cissé and Abderrahmane Sissako, as well as Mati Diop’s recent feature Atlantics (2019). Yet “to get French funding, you had to have a French producer”, Givanni says. “Directors had less control over their films.”

Keith Shiri, who founded Africa at the Pictures in 1991 while striving to bring African films to Britain, points out that the digital revolution has been especially liberating, “you no longer need your film endorsed by a producer in Europe; you can shape your own story”. However, he dismisses “so-called Nollywood” as “not cinema but telenovelas”.

Yet still, acknowledged African classics are not entrenched in world cinematic memory in the same way as Satyajit Ray or Akira Kurosawa. Perhaps because, Givanni ventures, many films were “never digitised; they were shown in cinema halls for experts, not for popular consumption. That’s beginning to change.”

Oblivion has been even greater for women such as Safi Faye of Senegal, who died on February 22, aged 79. Her debut Letter From My Village (1976), merging documentary and fiction, made her the first sub-Saharan woman to direct a commercially distributed film. Her feature Mossane (1996) was shown at the Cannes Film Festival. “Safi should have had more recognition and support,” Givanni says. “She felt it desperately.”

“Most archives on the continent are disappearing,” says Shiri, who is European secretary of the Pan African Federation of Filmmakers (Fepaci). He extols its 2017 agreement on the African Film Heritage Project with Martin Scorsese’s Film Foundation, Unesco and the Cineteca di Bologna, to restore 50 African films of world value. Those completed include films by Sembène and Mambéty. Shiri also hails as a breakthrough an agreement Fepaci made with the Kenyan government last month for an African Audiovisual and Cinema Commission in Nairobi, to preserve and restore films, fund film-making and support film schools. “For the first time, something like that exists in Africa. It’s going to change things.”

“Films need to be seen in their own countries,” Givanni adds, speaking from Fespaco. “Ouagadougou is fantastic because they’re being shown in stadiums full of local people.” While her “place of memory” sorely needs institutional backing, “we want it available to the African continent, because it has so much history”.

‘PerAnkh: The June Givanni Pan African Cinema Archive’, April 15-June 4, ravenrow.org. Francophone West African Cinema, to May 8, thegardencinema.co.uk

Find out about our latest stories first — follow @ftweekend on Twitter

Comments