Climate graphic of the week: One-third of Pakistan submerged by flooding, satellite data shows

Simply sign up to the Climate change myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Deadly flooding in Pakistan destroyed homes and decimated crops in what the country’s officials say is an unprecedented climate disaster, affecting an estimated 30mn people or about 15 per cent of the population.

About one-third of the country was still submerged last Tuesday when satellite data from the European Space Agency mapped the extent of the deluge.

The final toll is likely to climb beyond the early estimates of more than 1,100 people dead and nearly 1mn homes damaged by the flooding that was triggered by a combination of heavy monsoon rainfall and glacial melt.

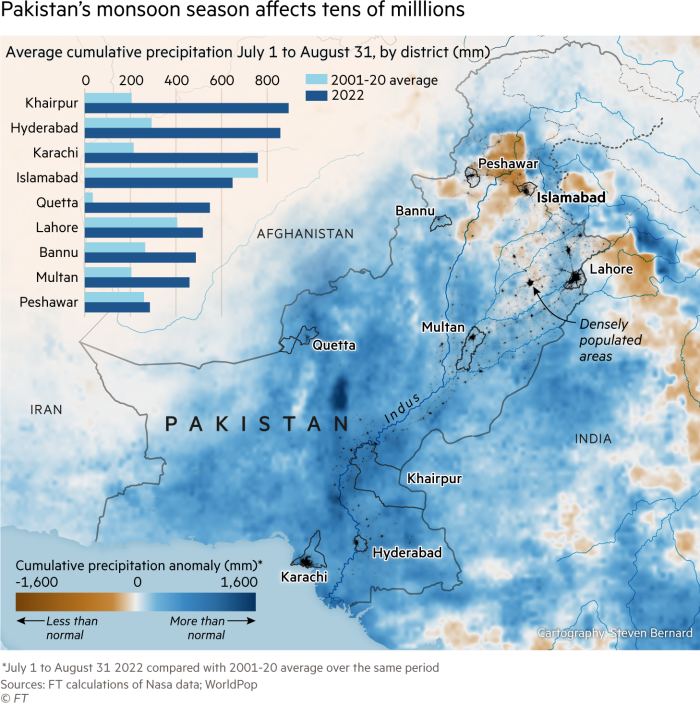

Monthly average rainfall surged across some of the country’s most populated cities and districts during July and August, according to data collected from a satellite mission run jointly by Nasa and the Japanese Aerospace Exploration Agency.

Hyderabad, a district in the country’s Sindh province, received more than 850mm (33.5 inches) of rain during July and August, nearly three times higher than the average of 290mm (11.5 inches) for that same period during 2001 to 2020.

The Sindh province, which borders the Arabian Sea, received almost eight times the average amount of rainfall for August, according to government data, wiping out rice and cotton crops.

Pakistan’s climate change and environment minister Sherry Rehman told the Financial Times earlier this week the flooding was the climate catastrophe of the decade. “In living memory, we have not seen such a biblical flood come to Pakistan,” Rehman said.

The rain is the latest in a series of extreme weather events to affect south-east Asia in recent months. An intense heatwave in India and Pakistan that lasted from March to May caused heat-related deaths, damaged wheat crops, and increased glacial melt in the Himalayas.

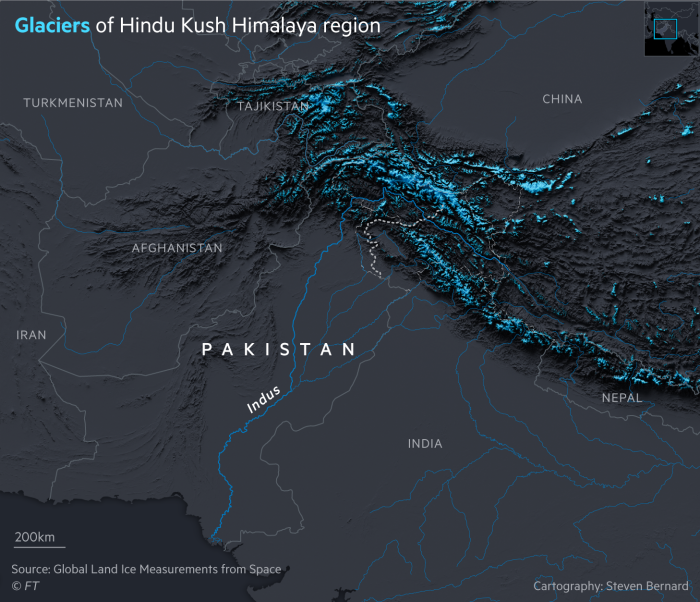

Although the majority of the flooding in Pakistan was due to rainfall, glacial melt has added to the effects of more aggressive monsoons, by releasing snow and ice melt into Pakistan’s river basins.

The Himalayas are often described as the “third pole” for being the largest mass of frozen fresh water outside the North and South poles.

Joseph Shea, a glaciologist at the University of Northern British Columbia, said the glaciers in the region had been losing mass for the last two decades, although not as quickly as glaciers in the Alps or western North America.

Glacial melt contributions to the Indus river basin were expected to peak by the middle of this century, Shea said.

The UN launched a $160mn appeal for Pakistan’s flood ravaged regions earlier this week after its government officials asked for help from the international community. The US government pledged $30mn in humanitarian assistance to Pakistan in response.

The catastrophic flooding underscores the growing urgency of resolving the international debate over who pays for the disastrous effects of climate change. Temperatures have risen at least 1.1C since pre-industrial times, mainly driven by economic growth in developed nations.

Developing economies have been pressing richer nations to pay for the damaging effects of climate change on their countries, which have contributed comparatively little to greenhouse gas emissions. Pakistan’s emissions are about 1 per cent of the global total.*

At Glasgow’s COP26 summit last year, developed economies rejected a proposal by less wealthy countries to create a new loss and damage funding facility. The issue is likely to be a touchstone subject at the UN’s next climate summit in November in Egypt.

*This article has been amended from the original to correct the percentage of emissions.

Climate Capital

Where climate change meets business, markets and politics. Explore the FT’s coverage here.

Are you curious about the FT’s environmental sustainability commitments? Find out more about our science-based targets here

Comments