Electric and hybrid trains power ahead to cut emissions

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The sound of trains departing from London’s St Pancras Station on the 70-mile journey to Corby, in Northamptonshire, has changed.

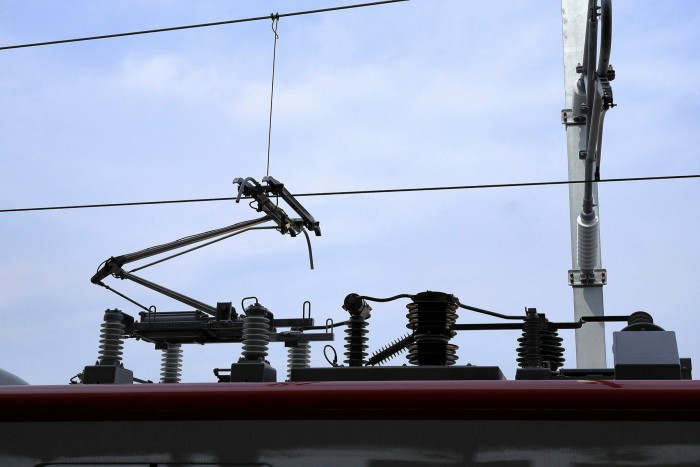

After 2009, when the route reopened to regular services, passengers heard a sharp crescendo of revving from the train’s underfloor diesel engines. Since May, however, they have heard the steadily-rising whine of far quieter electric motors.

This change is one of several tangible signs on the journey of how the line has been transformed. Now, overhead wires deliver 25,000-volt electricity to trains running all the way to Corby; previously, the wires had stopped 26 miles further south, at Bedford, meaning diesel trains were necessary to travel the full distance.

The new electric trains also accelerate more quickly than diesel-powered alternatives and their improved journey times are expected, based on past experience, to shift more traffic to rail and away from the roads.

The Bedford to Corby electrification is part of a multibillion-pound effort to improve the overall efficiency and carbon footprint of the UK’s rail system by switching far more trains from polluting diesel to cleaner electric power.

Network Rail, the UK’s rail infrastructure owner, says electric train journeys generate 20 to 35 per cent less carbon per mile than those powered by diesel.

The programme is being extended throughout Great Britain: services on the busy Edinburgh to Glasgow route in Scotland switched to electric power in 2019 and the route between London and Cardiff went electric last year.

Similar efforts are under way in many other countries. Germany, which already has a high proportion of its national network electrified, continues to electrify lightly-used lines. India has been electrifying thousands of kilometres of its routes every year, in recent times,

Steven Hart, lead strategic planner for the UK’s Network Rail, says the aim is to take as many emissions as possible out of the rail system. Some 747km of British routes were electrified in the six financial years to 2018-19 but the UK still has only 38 per cent of its rail network powered by electricity.

According to Hart: “[There’s also] that longer-term piece about getting rid of all diesel trains. You also have what is often dubbed the ‘sparks effect’. People find electric trains more attractive so they ditch the car to move over to trains.”

The programme is being assisted by the emergence of a range of new technologies. These include the development of new trains capable of being powered both by diesel motors and by overhead electric wires. Such technology should ensure that trains run far less often on diesel power when overhead lines are available.

Right now, Japan’s Hitachi is delivering more than 500 carriages for trains with such a capability both to Great Western Railway, which operates services from London to Cardiff, Bristol and western England, and to LNER, operating services from London to Yorkshire, north-east England and Scotland.

Mark Gaynor, head of railway planning at the Rail Delivery Group, which represents train operators, says “bi-mode” trains, which barely existed in the UK five years ago, now account for 7 per cent of the total passenger fleet. “We certainly are seeing more units with that technology,” he says.

He expects interest in such technology to grow. Cost pressures and unforeseen complications have meant that electrification in many places is running more slowly than expected. But bi-mode technology at least offers a temporary solution: it avoids the need to electrify tunnels and other less accessible areas while still bringing the benefits of electrification to the wider route.

Gaynor also expects greater interest in “tri-mode” trains equipped with batteries as well as diesel motors and roof-mounted pantographs for connection to overhead current. Porterbrook, a rail leasing company, is currently converting old pure-electric passenger trains into tri-mode passenger trains and express parcel delivery units.

“You use power where it’s available, run on battery power where it’s not, then you have that diesel, go-anywhere capability as well,” Gaynor explains.

Meanwhile, the more efficient pure electric technology continues to improve. Electric trains’ motors traditionally relied on direct current electricity but technological advances in recent decades have allowed their replacement with equipment powered by alternating current (AC).

The new motors are substantially lighter and consume between 10 and 30 per cent less energy than the old versions. In addition, they have allowed the introduction of “regenerative braking” on lines electrified with third rails — including some of the UK’s busiest commuter routes. A train using regenerative braking generates electricity in its motors when slowing and feeds this back into the network for another train to use while accelerating.

“That move to AC motors clearly gives an efficiency improvement,” Gaynor says.

Yet, for the most remote routes, it may never make sense to string up electric wires. Electrification’s economics are far poorer where the high capital costs of the work are spread across a small number of services. Such questions are still more acute in countries such as the US, where the vast rail network is barely electrified and where most traffic is heavy, energy-intensive freight.

Nevertheless, Hart insists that technology is being developed to ensure that any area could be served by trains making no carbon emissions. Porterbrook is experimenting with a train it calls Hydroflex, which uses carbon-free hydrogen fuel cells to power its electric motors. France’s Alstom has sold a similar hydrogen-powered passenger train — which it calls the iLint — to a number of European countries. And US group Caterpillar has launched a hydrogen-powered heavy freight locomotive that has gone into operation with Canada’s Canadian Pacific.

Twice weekly newsletter

Energy is the world’s indispensable business and Energy Source is its newsletter. Every Tuesday and Thursday, direct to your inbox, Energy Source brings you essential news, forward-thinking analysis and insider intelligence. Sign up here.

Dizzying advances are possible, Hart says, because of the billions of dollars being invested in greening motor vehicles — the transport mode from which programmes such as the Corby electrification hope to steal traffic.

“We’re taking a lot of advances that have been made in the automotive sector and we’re directly translating that into a rail environment,” Hart says. “We’re able almost to ride the coat-tails of the research and development that’s happening in the automotive sector.”

Comments