Black artists matter: The winds of change are blowing through the art world

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Melissa Thompson gazes from the canvas, her hands extended loosely over the arms of an upholstered armchair in a pose redolent of Velázquez’s famous portrait of Pope Innocent X. Set against a background of gorgeous floral motifs, the resident of the gritty London district of Dalston (pictured) appears majestic, confident — and entirely at home in her surroundings.

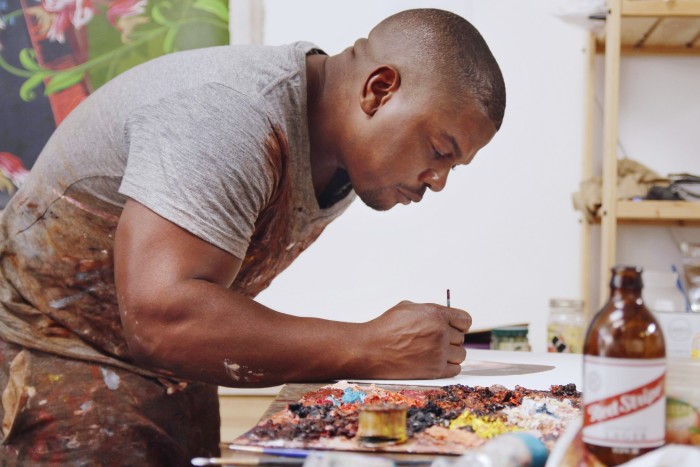

Kehinde Wiley, the US artist who painted it, borrows the visual language of the Renaissance and Baroque era to imbue his paintings of ordinary black and brown people with the powerful bearing of those more often found in grand galleries or stately homes.

“I am copying the body language of power and juxtaposing that with people from neighbourhoods around the world — but increasingly underserved neighbourhoods,” he told an online audience at a recent talk hosted by auction house Sotheby’s. “Imagine what that feels like for the young black girl who walks into the William Morris Gallery [in London] and sees herself or her mother or someone who looks like her.”

The killing of George Floyd in the US, which sparked protests around the world in May and reignited the Black Lives Matter movement, has brought a new urgency to issues of historic injustice suffered by black communities. As the protests raged and calls for reform and redress have grown louder, a light has been shone on all areas of society where black people face barriers — including the art world.

Museums and galleries, dealers, auction houses and advisers are facing fresh demands for action over the overt structures or unconscious biases that have helped exclude today’s black artists — as well as how to right the wrongs suffered by previous generations.

The demands for change come even as the picture for black artists is improving, with many enjoying critical and commercial success in the past few years, their paintings and sculptures increasingly sought out by museums and collectors and their careers supported by leading commercial galleries.

“It’s different this time,” says Pamela Joyner, an African-American businesswoman and art collector. “The whole of the art ecosystem has been activated in a way it wasn’t then. In order for an artist to be written into the history books they really need support from the critics and curators, support in the distribution channel — which is the gallery system — and from key collectors — not just small groups, but tastemaking collectors . . . If you look across the board today, it is happening.”

The standout superstar of the auction market in recent years has been Jean-Michel Basquiat, who became the most expensive US artist at auction when a 1982 painting by him sold for record-shattering $110.5m in 2017. Basquiat died in 1988, with buyers already ravenous for his works, and his paintings have steadily risen in value since. But living as well as deceased artists of colour have also seen the market for their works rise fast in the past few years. The auction record for Wiley, for instance, was broken in June, when “Le Roi à la Chasse II” sold for $350,000 with fees at Sotheby’s New York. Another of his portraits “Alexander I, Emperor of Russia”, fetched £175,000 a month later in London.

Such sums represent a fundamental shift from the conditions in the 20th century, when — aside from Basquiat, whose success is seen as exceptional — most artists of colour were locked out of the art world system. Efforts in the late 1960s and 1990s to break down the barriers to black artists foundered after an initial burst of attention, leaving little permanent mark. Largely excluded by institutions, they were written out of the history books, ignored by dealers and struggled to make a living without a viable collector base.

With her husband, Fred Giuffrida, Ms Joyner has made it the work of three decades to fill in these gaps in art history, amassing a collection of over 400 works by black and African artists from 1945 onwards, with a focus on abstraction. “It’s a mission-driven collection,” she says.

Her efforts go far beyond supporting artists by purchasing their work. The depth of the collection gives her leverage when lending or gifting works to museums and galleries which are keen to rectify the absence of works by artists of colour. She can help ensure, for instance, that artworks go up on the wall and not into the storage room; and that researchers or curators do the academic work needed to flesh out the long-neglected knowledge base of black artists.

A trustee of the Tate Americas Foundation, which supports the UK’s Tate gallery group, she made a recent gift to the museums of an important “drape” painting by Sam Gilliam, who pioneered this three-dimensional form of abstract art — later adopted by other artists — by hanging painted canvasses without frames. “The idea that black artists are coming into greater visibility started 5 or 6 years ago,” she says. “Institutions in the UK played a meaningful role in that process — Tate in particular.”

Christopher Bedford, director of the Baltimore Museum of Art, describes Ms Joyner as a “collector-activist”. “By working with her, museums will reap the economic benefits and at the same time be able to advance a more just and true history of art.”

Museums have been slow to play their part. In the ten years to 2018, just 2.4 per cent of all works acquired by or given to 30 big US institutions were of work by African-American artists, according to research by the advisers Art Agency Partners and Artnet News.

Bedford has been a leading protagonist among gallery directors accelerating this process, and propelling deeper changes in relationships between artists, curators, dealers, collectors and audiences. Since his arrival in 2016, the Baltimore Museum of Art has diversified its curatorial staff and board with new appointments and put on exhibitions of black artists’ work. In 2018 it went further still, selling seven works in its collection by well-known names such as Andy Warhol and Robert Rauschenberg, raising $18m, which it used to acquire works by black and women artists including Charles Gaines, Faith Ringgold and Amy Sherald.

Some worry that the racism experienced by important artists from previous generations — those who were denied the commercial benefits enjoyed by white artists and today’s younger stars — continues to make itself felt, since the current prices of their work have suffered by starting from a grossly unequal level. Hannah O’Leary, Sotheby’s head of modern and contemporary African art, says: “If you’re an artist who has 50 or 60 years behind you and then you see a young artist in their twenties making six figures at auction, with very little critical success behind them, it seems incredibly unjust.”

Museums can use this historical bias to set the record straight by buying works into a public collection, but also help the artists who created them, Bedford says. “You’re taking advantage of a [purchasing] opportunity created by systemic racism, but you’re also creating a market condition in which those artists who are still living and producing can substantially benefit from that market adjustment.”

Auction houses, too, have a role to play. Wealthy collectors and their art advisers often seek the guidance of auction experts in judging which artworks should count as “important” when building a collection. Auction houses can also signal a work’s greater value when deciding how it should be promoted in a sale. Until 2018, for instance, the work of Norman Lewis, a pioneering but neglected figure in the Abstract Expressionism movement of the 1950s, had yet to surpass the $1m mark at auction. Last November, however, the record was smashed when his painting “Ritual” fetched $2.8m including fees, trebling its previous record set in 2015.

Part of the explanation lies in “positioning”. The decision as to whether an object should appear at a daytime sale, as opposed to a glitzy evening auction, can mean a difference of millions of dollars in sales. It is unlikely to be a coincidence that Lewis’s auction record — and that of fellow African-American artist Charles White — was broken on their first inclusion at an evening art sale at Sotheby’s.

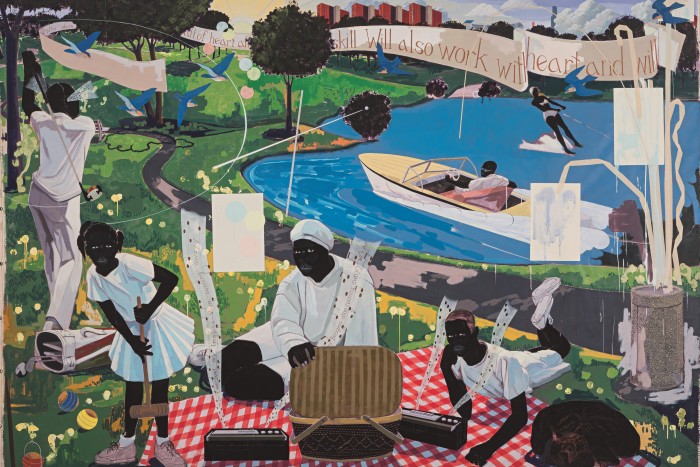

The headline sales give the impression that the market for living artists of colour has been booming over the past five years. The highest auction price paid for the work of a living African-American artist was set in May 2018, when Kerry James Marshall’s “Past Times” was bought at Sotheby’s for $21.1m by the rap artist and producer Sean Combs, quadrupling the previous auction record.

But Bedford warns that the market is distorted by the outsized values of a few stars, with the rest of the pack still lagging behind. Basquiat alone accounted for 77 per cent of the total $2.2bn auction sales of African-American artists in the ten years to 2018, according to the research by Art Agency Partners and Artnet.

There is also a big distance between the prices for the top black artists (bar Basquiat) and their white peers. “If you want to see how little movement has occurred, look at the auction record for Norman Lewis and compare it with the auction record for Jackson Pollock or Mark Rothko,” Mr Bedford says. All were instrumental in the birth of Abstract Expressionism, yet Lewis’s most expensive work achieved less than $3m while Rothko’s fetched $89m.

The benefit of rising prices for a few is likely to be shared more widely, Joyner says, as buyers priced out of bidding for the stars seek out related artists who, as yet, remain less well known. “The older generation of artists represented by Sam Gilliam have been highlighted in part because of the success of the generation after them,” she says.

Could Covid-19 threaten the process of rebalancing by acquisition in art institutions? Tight museum budgets are set to become even tighter as visitor income falls because of coronavirus restrictions. Bedford believes some may try to use the pandemic as an excuse to delay change, despite the scrutiny prompted by the Black Lives Matter movement. “The great peril of the moment is that institutions who don’t have an equity agenda at their core will use Covid-19 to set aside once again that justice-driven agenda.”

Public art has also become a flashpoint, from statues of Bristol’s Edward Colston and Oxford’s Cecil Rhodes to those of Confederate army leaders in the southern US. Wiley in December unveiled his response with “Rumors of War”, a towering bronze of a young African-American man in urban clothes sitting astride an enormous horse, subverting the triumphal, militaristic imagery of equine statuary.

“You have someone who could be anyone but who functions mostly as a symbol for young black men in America who oftentimes increasingly are targets,” he says.

For Joyner, the change in sentiment across the art world is not just a passing moment. “An emphasis and focus on artists of colour had started before Black Lives Matter — but the mood for assistance is exacerbated by this moment.”

This article is part of FT Wealth, a section providing in-depth coverage of philanthropy, entrepreneurs, family offices, as well as alternative and impact investment.

Comments