Curator Amin Jaffer: ‘There are endless possibilities for learning’

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Amin Jaffer is in demand. The former Victoria and Albert Museum curator is busy overseeing a new space in Paris, which will house jewels and antiquities owned by the Al Thani dynasty of Qatar. Meanwhile, an exhibition he guest-curated on the early 20th-century prince and patron, the Maharaja of Indore, opened recently at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris.

Jaffer is also taking on a new role this year at Frieze Masters, working alongside independent curator Norman Rosenthal on the Collections section of the fair. This is a section that comprises a group of eight stands, each of which will present small “museum-type” exhibitions on focused themes.

“Sir Norman is curating four and I am curating the other four. The themes will vary; in my section, there are two galleries whose works follow the influences between east and west,” Jaffer says.

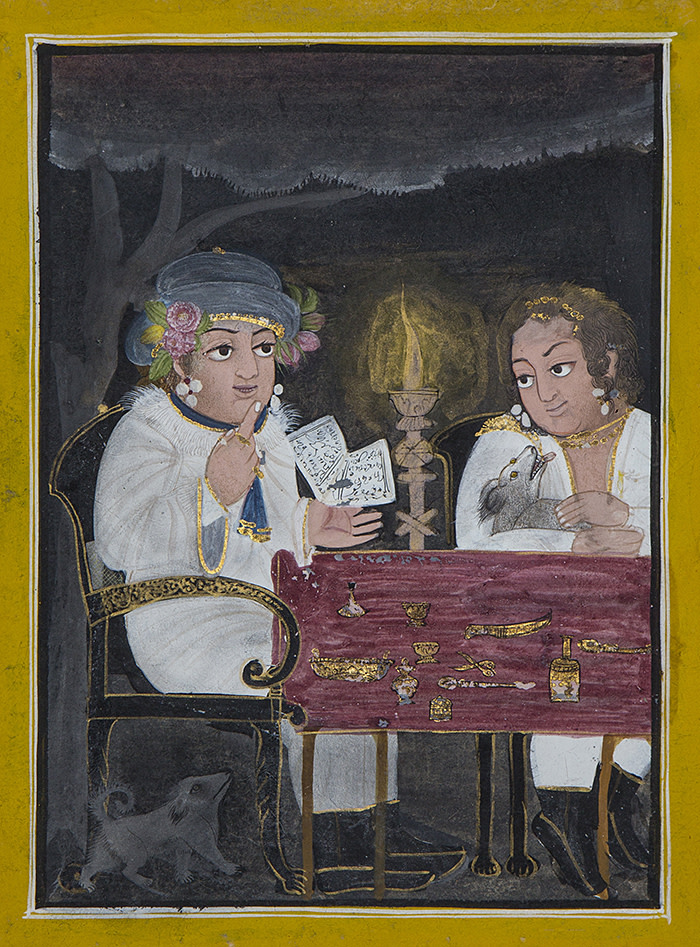

These include a show of Indian miniatures (at Galerie Alexis Renard) representing westerners, shedding light on South Asian perceptions of Europeans in the pre-colonial period. “These paintings highlight the peculiarities of western behaviour, dress and physiognomy,” Jaffer says. In another twist on east-west relationships, material on show at Galerie Kevorkian reveals how westerners formed collections of works found or excavated in Asia.

Jaffer’s two other presentations explore how late 20th-century art from Asia draws on elements of ancient tradition. At Grosvenor Gallery, “The Indian modernist painter S.H. Raza’s minimalist monochromatic works from the 1970s are shown alongside tantric miniatures and lingams that share a similar geometric simplicity,” Jaffer says. And to complete the set, Gregg Baker Asian Art gallery is showing Japanese Zen Buddhist works alongside modern Japanese painting.

The Frieze Masters initiative, a mix of curatorial and commercial elements, seems the perfect fit for Jaffer, who was previously international director of Asian Art at Christie’s in London. He stresses that “in this instance [at Frieze Masters], I am not aware of values of any of the works. My role is to ensure that the choice of works on view presents a coherent idea or thesis.”

He joined Christie’s in 2007 after leaving the V&A where he was first a research fellow, moving up to senior curator. At Christie’s, he worked with a team of colleagues to help develop the Indian market, integrating collectors there into the wider art world.

“In those days [pre 2010], India presented itself as an enormous opportunity,” he says, adding that he played a part in launching Christie’s first auctions in Mumbai in 2013. Was it hard to adjust, moving from an academic environment to a business milieu? “Not one bit! My Gujarati merchant genes kicked in right away. The works on view are constantly changing; there are endless possibilities for learning.”

Jaffer’s life journey covers continents. He was born in Rwanda, and the Francophone family of his father were businesspeople settled throughout the Congo. His mother’s English-speaking family, which hailed from Nairobi, was more academically inclined, he says.

In 1983 he was sent to Montreal, spending his formative years studying at the University of Toronto.

Meeting Peter Kaellgren, a curator in the European department at the Royal Ontario Museum, changed his outlook. “Under his tutelage, I began to research and write about movements in art as represented on decorative and functional objects, starting with ceramics.” Kaellgren advised him to embark on a degree in the early 1990s at the Royal College of Art in London, which ran a masters programme at the V&A in history of design.

So began a long association with the South Kensington museum. At the V&A he produced what he describes as the “definitive book on British furniture from India and Sri Lanka (Furniture from British India and Ceylon, 2001)”. “I hope that somebody will update the findings of 20 years ago and correct my many errors,” he says, self-deprecatingly.

In 2004, he co-curated with Anna Jackson, now keeper of the Asian department, the blockbuster exhibition Encounters: The meeting of Asia and Europe, 1500-1800, which explored how Europe and Asia overlapped in the pre-colonial period.

“Although it was championed by the then director, Mark Jones, support for the [Encounters] show within the museum was limited. However, it proved to be a success, visited even by political luminaries working with Asian countries,” he says. Jaffer evidently has an enviable contacts book, and it is no surprise that his current post is at the epicentre of the Middle Eastern art world. As senior curator of the Al Thani Collection, a post he took up early 2017, Jaffer’s work for Sheikh Hamad Bin Abdullah Al Thani, a cousin of the Emir of Qatar, focuses on managing, researching and publishing his collections, curating exhibitions, and acting as a conduit for his philanthropic activities. Presumably, he helps Sheikh Hamad build up his reputable collection of Indian jewellery? “He is a focused and erudite collector who makes his own acquisition decisions,” Jaffer says.

Early next year, jewels, paintings, antiquities and medieval manuscripts from the 6,000-strong Al Thani Collection will go on show in a gallery at the revamped Hôtel de la Marine in Paris following an agreement signed with the Centre des Monuments Nationaux (CMN), the government body which manages the 18th-century property.

The project involves working with the CMN on the design, display and outreach initiatives. The first exhibition will coincide with the reopening of the historic venue: the collection will be shown over a period lasting at least 20 years. “This is a collection of encyclopaedic scope, spanning from the ancient world to the present day,” Jaffer says.

“As part of the agreement, the CMN will receive an generous donation which will support the restoration of the Hôtel de la Marine as well as other heritage projects in France,” says a project statement. The French press reported that the Al Thani Collection Foundation gave €20m towards the initiative; the foundation declined to comment.

Asked who benefits most — the city of Paris or the state of Qatar — Jaffer believes it is a win-win for all involved. “It provides us with the chance to develop a programme to show the collections, and to partner with other curators and institutions.” Typically, he is not daunted in the slightest by the long-term commitment. “It seems exciting!” he exclaims.

Follow @FTLifeArts on Twitter to find out about our latest stories first. Listen and subscribe to Culture Call, a transatlantic conversation from the FT, at ft.com/culture-call or on Apple Podcasts

Comments