This man can find your dream watch

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Back in May, against a backdrop of headlines about how the secondary watch market had significantly cooled, came news of an extraordinary price achieved for a ’60s Cartier Crash. The watch almost doubled the previous record for the model when it sold for more than $1.5mn at auction. It was about as desirable as a Crash can get, made in the London workshops in 1967 and new to the market… even so, $1.5mn? Even more remarkably, this price was not achieved at Phillips, nor Christie’s, nor Sotheby’s; nor even at Bonhams, Antiquorum or Dr Crott in Mannheim. Instead, the sale was made via an online platform called Loupe This, a little over one year old, headquartered in West Hollywood, California.

This extraordinary result focused attention on the usually discreet world of the high-value vintage watch dealer. Prima facie it seemed to be a result that had come out of nowhere. In fact, it was about 25 years in the making, which is about how long Loupe This’s 43-year-old co-founder Eric Ku has been trading watches: “In college, I was trading stocks and was able to buy some nice watches.” After graduating Ku went to work in various start-ups in the Bay Area but, he says, had “this moment of clarity on my last job, where the FedEx driver came and dropped off 10 boxes at my office, and they all had watches inside. I was like, ‘What the hell am I doing here?’ I quit that day and never looked back.”

Ku started the auction platform with business partner Justin Gruenberg during Covid and describes it as a more efficient way of selling watches compared with traditional auction houses, where the process can take from six months to a year. Loupe This charges a flat seller fee of $500, a 10 per cent buyer fee and counts its turnaround in weeks rather than months. But it takes much more than lower fees and quicker sales; it is as much personal reputation as product that matters, whence the watch collector’s maxim “buy the seller not the watch”.

With his close-cropped hair, neatly maintained moustache and fine-rimmed spectacles, Ku looks like a professor. I have heard rumours that he has an IQ of 180. Speaking in Gatling gun-like bursts, he outlines the research methods he applies. “You’re looking at a watch and somebody asks, ‘How do you know this is real?’ If you ask an old-generation dealer, they will probably give you an answer to the effect of, ‘Oh, I’ve seen watches like this for the past 30 years. I’ve handled them, I’ve seen them. I know they’re real’ – some nebulous type of answer like that. When somebody asks me, I’ll go and research old auction catalogues. I’ll say something like, ‘In this 1989 Antiquorum catalogue, you can see that this watch existed, at this time, in this configuration.’” He also talks of illuminated loupes and “using a Geiger counter to assess the originality of the radiation”.

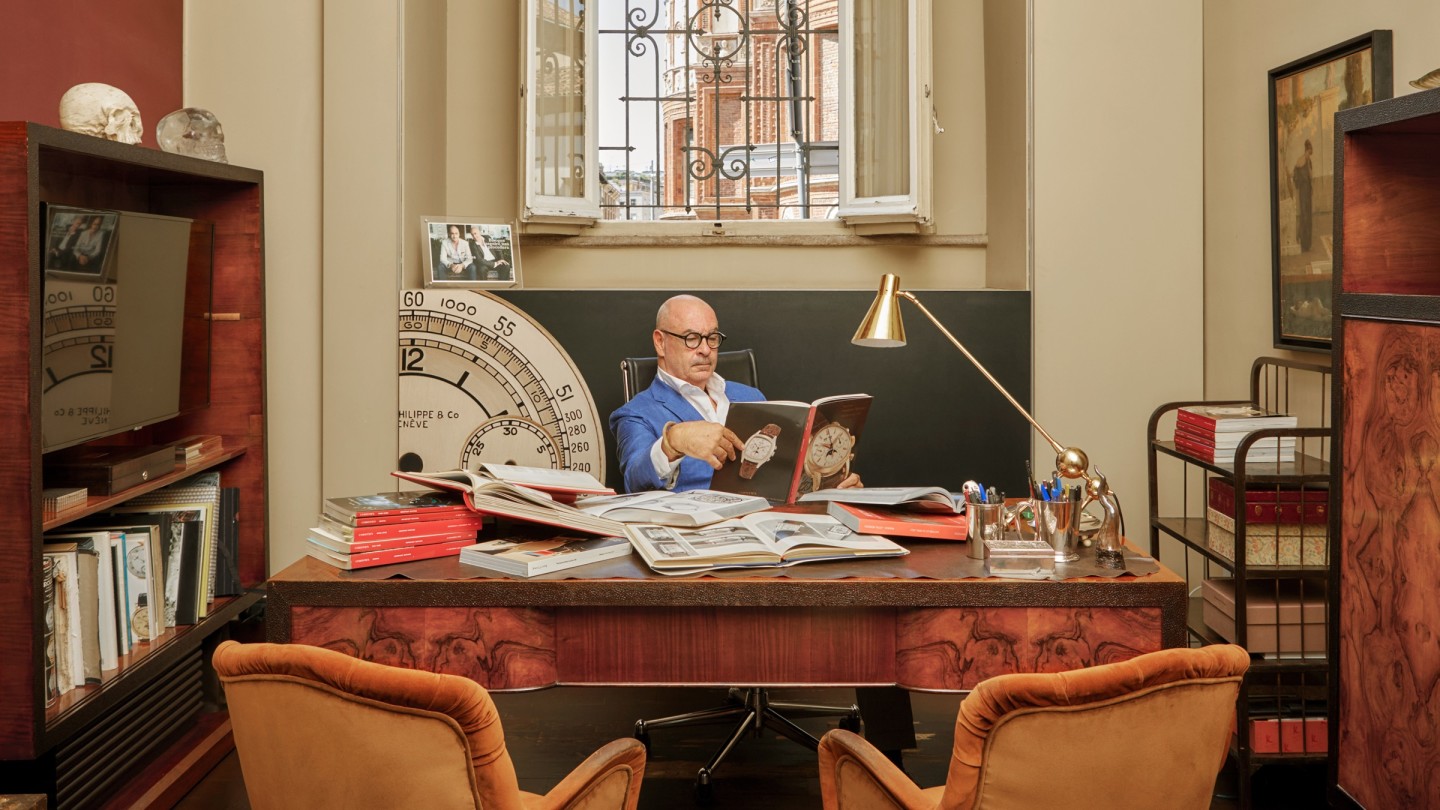

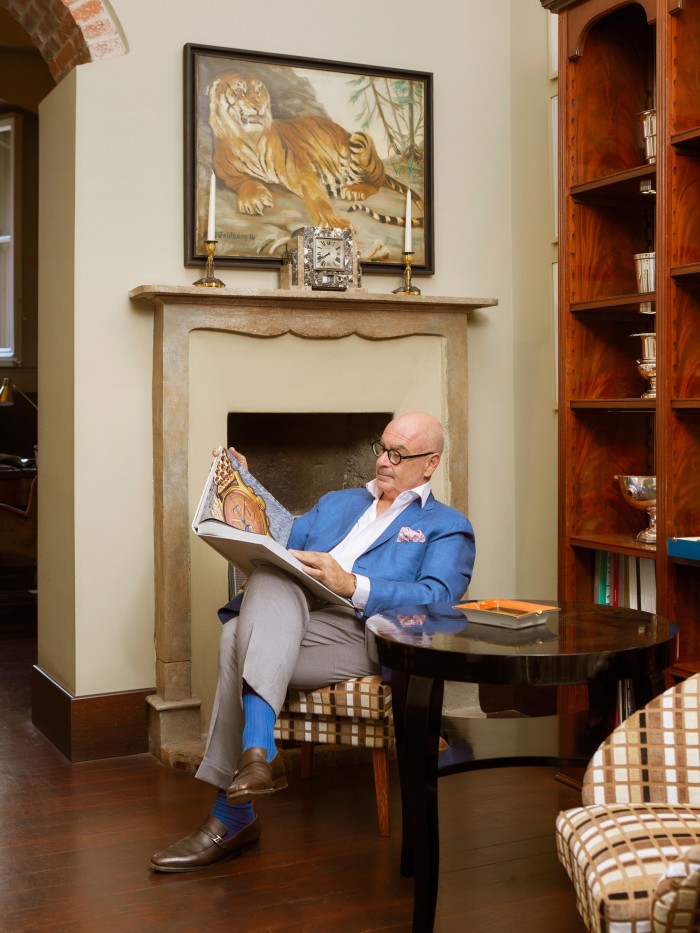

The use of Geiger counters, microscopes and academic research methods are testament to the increasing values of certain vintage models, with tiny and near-undetectable differences moving prices by six figures or more. “A big-crown Rolex Submariner with original radium can go for over half a million. But if the radium has been replaced, it drops down way below $200,000,” explains Milan-based dealer Max Bernardini, a charming Italian marquis who cuts a Byronic figure in cobalt-coloured tailoring.

Now in his early 50s, Bernardini got into watch dealing when he sold the watch he received for his 16th birthday, bought a Rolex “Bubbleback” and came away with a 500,000 lira profit. His first customer of note was Diego Maradona. “He told me, ‘I was born poor. I have all this money. And I don’t know how to behave.’ He showed up with five big, blingy gold watches,” he recalls. “I took it from there and changed his tastes.”

1950 Patek Philippe gold ref 1518, POA, 2tonevintage.com

1940s Rolex Ref 4313, POA, davideparmegiani.ch

Bernardini’s Milan store is a temple to old-school elegance with vintage Vuitton trunks converted into travelling bars or cigar boxes and a full-time butler on hand. But while the surroundings are seductive, the real Bernardini difference is expertise. “It’s a beautiful watch, but you don’t need to come to Bernardini to buy a 5711 Nautilus: there’s nothing I can tell you about it that you can’t find online. Instead, I have a few areas of expertise: sector dials, the pre-Daytona world, and most of all, 1518.”

Patek Philippe’s 1518 is as historically important as it is understatedly chic. The first series-produced perpetual calendar chronograph, it was made during the ’40s and early ’50s. It may only measure 35mm across but a nice example in yellow gold costs between $500,000 and $800,000. In pink gold, prices start from $2mn. Prices have been on the rise since the exceptional Egyptian royal family “pink on pink” example fetched $9.57mn at Sotheby’s in New York last winter.

“Interest in this model has increased in the past nine months and we can only guess what one of the four known steel ones would sell for… north of $20mn to $25mn?” ponders Bernardini. “I’m the man who has sold the most 1518s in the world. Every time I sell a 1518, I know where it is. In 32 years, I’ve traded about a third of the 281 produced.” Think of it like an art dealer knowing exactly where all the great privately owned Blue and Rose Period Picassos are; at this level it is like dealing in major masterpiece paintings, and rather than selling them for the highest price he prefers to place them in the right collections.

Bernardini has found the contemporary watch boom bad for business. “This bubble hurt my business very much. Because when I talk to investors and their family offices there is always some spoiled brat, usually a cousin or nephew of the main decision maker, who pulls out his phone and starts talking about [the ecommerce site] Chrono24 and asking if I am capable of guaranteeing the same returns.” He points out that often pieces end up on Chrono24 because they have failed to sell privately or at auction and that the price at which a watch is offered is not necessarily that at which it sells. “As a curator I don’t guarantee returns… I can guarantee quality and expertise.” The slowdown in modern steel sports watches has seen the pendulum swing back. “I’ve recently been called by some of the family offices for whom I consult to reassess investments in vintage watches. They are not so convinced by these 20-year-old kids after all.”

However not all twentysomethings are instant experts, as Davide Parmegiani will happily tell you. Fifty-six-year-old Parmegiani moved his store from Milan to Lugano over a decade ago and in 2019 he took a half share in Monégasque auction house Monaco Legend Group, where his 23-year-old son now works with him.

Parmegiani is spoken of as the most important of the super-dealers. To listen to his mellifluous Italian-accented English is to bathe in the history of the last four-and-a-half decades of the vintage watch business. He vividly recalls the excitement of travelling to America in the 1980s and finding a land of milk, honey and superb vintage watches where he paid $80,000 for his first 1518 and placed it in a collection for $100,000. But he will talk just as passionately about an obscure rectangular Audemars Piguet from the 1930s that he recently placed in the celebrated Goldberger collection.

Like others he has been happy to see the market for sports watches has peaked: “It was just speculation by people who would like short-term profit, but it doesn’t affect my core business which is advising about building collections of vintage watches.

1920s Audemars Piguet white-gold pocket watch, POA, 2tonevintage.com

1950 Patek Philippe ref 2424, $95,000, 2tonevintage.com

“Vintage collectable watches are a very small niche compared to cars, jewellery or art: a nice auction of watches is possibly $20mn. If you go to an evening sale of contemporary art, one painting is $40mn to $50mn. The watch market and the passion for watches still have a lot to give, financially speaking, but the market has to be taken care of by the people that understand. There’s still a lot to do.”

Ali Nael started collecting watches when he was an oil trader, but in 2014 decided to go into the vintage watch market. In 2018 he opened 2ToneVintage in Singapore. “In the past two or three years, more financial institutions and banks have started to look at watches as an asset class. They’re not yet ready to dive into taking watches as collateral but I think things are changing,” he says.

“I resisted the hype in the past two-and-a-half years because I wanted to keep focused on vintage with a pure message and pure identity. Even my colleagues were like, ‘What are you doing? Why are you refusing money?’ Many times, we have sold watches for millions that don’t make it onto the website because we know who wants them.” He says his biggest deal so far has been $4.1mn for two Rolexes, but he would much rather talk about the growing interest in pocket watches. “In the past month I sold one collector three high-complications pocket watches for a few hundred thousand dollars.” When I ask him to describe his business simply, he says: “I am on a mission to make people unafraid of going into vintage.” The door’s open – albeit at a price.

Comments