Imbalances in housing wealth demand radical tax reform

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

As governments scramble to find ways of paying down the huge debts they accumulated in the pandemic, many are naturally hunting for new sources of revenue. Could they look again at domestic property, an asset long granted all kinds of tax privileges the world over?

Of course they could. Governments badly need to boost taxes in the medium and long term, especially those in Europe that are now having to subsidise energy costs because of Russia’s Ukraine war. But property owners have, in the past, proved themselves able to defend their interests. An alliance of the wealthy and the middling rich comes together and blocks reform. And it could do so again, given the slightest hint of a new assault.

It is into this politically treacherous territory that the OECD, the rich economies’ grouping, has trodden. Its advice, published this summer in a report called Housing Taxation in OECD Countries, is carefully phrased, as befits a club of 38 nations with varied political leanings.

The message to governments is clear, though: look favourably at raising property taxes; think about reducing or removing reliefs and exemptions that disproportionately benefit the rich at the expense of the less well-off, particularly younger people struggling to get on the property ladder; and consider whether the tax treatment of second homes (not to mention third, and 10th, homes) is reasonable in an age of inequality.

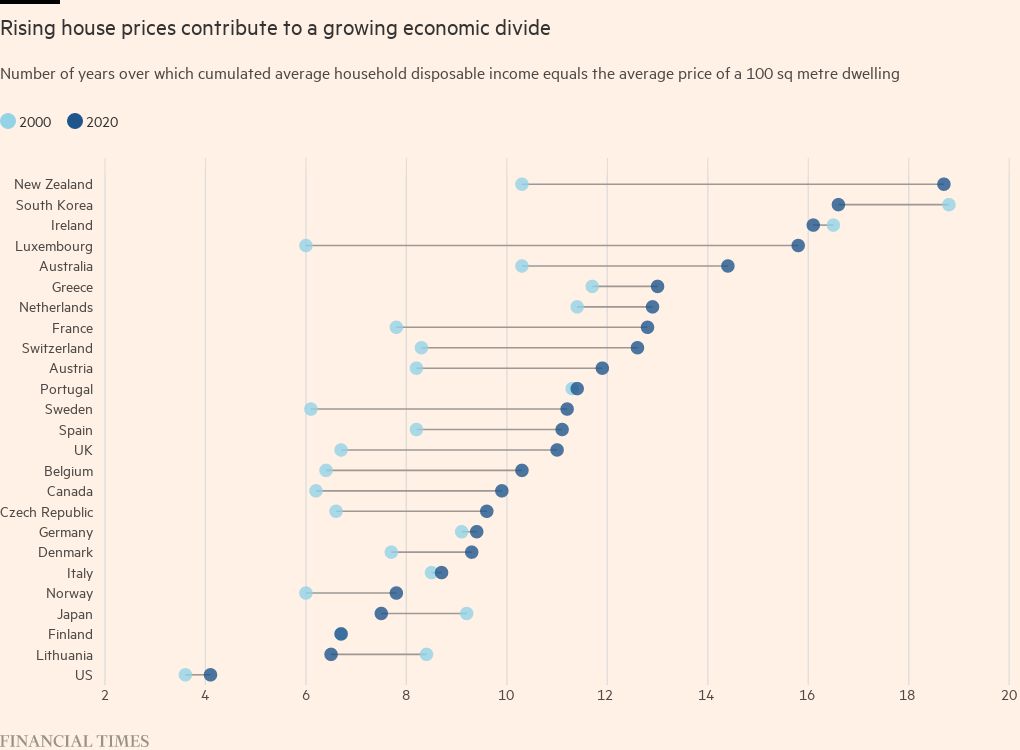

The report’s starting point is the unequal distribution of housing wealth, with assets concentrated among high-income, high-wealth older people. Interestingly, these owners also hold a disproportionate share of housing debt, presumably because they can raise money easily and don’t want to lock their own cash in bricks and mortar when it might be profitably deployed elsewhere.

However, for all their attractions and the political controversy they often generate, property taxes produce only around 6 per cent of the total tax take in a range of OECD states, says the report. The revenues raised have also failed by a wide margin to keep up with rising house prices: recurring property taxes — levied regularly on ownership — rose by only a quarter in 1995-2020 while real house prices nearly doubled.

So the report’s main advice is to reform recurring taxes by ensuring that the property valuations are regularly updated. England is a case in point, having a valuation date of April 1991.

Reforms would make it easier to raise more money fairly, says the OECD. It would also allow reductions in property transaction taxes, such as UK stamp duty, that would encourage a transference of more homes from older to younger owners and promote mobility.

More controversially, the report backs capping the capital gains tax exemptions on the sale of main residences, and not allowing owners to take profits on such homes tax-free. This is particularly tricky as middle-income householders are likely to have more of their wealth concentrated in their main residence than the very rich, who in many cases have multiple properties and financial portfolios. A lot would depend on the level at which such gains were capped.

In addition, with an eye on all those wealthy mortgage borrowers, the OECD suggests “gradually removing or capping mortgage interest relief for owner-occupied housing”, as has been done in the UK and some other countries, though not in the US where it remains a live issue.

Finally, the OECD would not be the OECD if it did not call for a crackdown on tax evasion, saying “strengthened reporting requirements”, including to the tax authority plus international exchanges of information, are “key to ensuring housing taxes are enforced properly”.

For wealthier property owners, it makes for sobering reading, but governments rarely rush to implement what the OECD has to say.

Stefan Wagstyl is the editor of FT Wealth and FT Money. Follow Stefan on Twitter @stefanwagstyl

This article is part of FT Wealth, a section providing in-depth coverage of philanthropy, entrepreneurs, family offices, as well as alternative and impact investment

Comments