Q&A: How is Big Tech dealing with ethical problems?

Simply sign up to the Technology sector myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

The application of artificial intelligence in businesses and the public sector is causing huge ethical divisions — both inside and outside tech companies.

Big-tech groups leading research into AI, in the US and China — including Google, Amazon, Microsoft, Baidu, SenseTime and Tencent — have taken very different approaches.

They differ on questions such as whether to develop technology that can ultimately be used for military and surveillance purposes, and to whom these systems may be sold.

Some have also been attacked for the algorithmic flaws or distortions in their programs, where computers inadvertently propagate bias through unfair or corrupt data inputs — such as Amazon’s experimental hiring algorithm that penalised female applicants. The company has since scrapped it.

But the debate around ethics in AI is not only a philosophical one. Governments around the world are drafting national regulations for AI, to prevent ethical conflicts and biases. So is the EU. This is particularly important as smart decision-making systems are used more in public services, such as social welfare, law enforcement and healthcare.

As companies develop new AI products, they will have to ensure these systems are transparent, fair, explainable and compatible with existing laws and regulations. How Big Tech addresses questions of bias in AI will affect not only public perception and trust, but also companies’ ability to do business in specific countries, the AI products in their pipeline and the type of talent they can attract.

What does this mean for companies building machine-learning algorithms? Will this affect their business models? Will questions over ethics impact the products themselves? Will it affect their sales and revenues? How have AI ethics controversies affected the workforces of these companies? What will compel companies to examine their algorithms for ethical problems — is it regulation or something else?

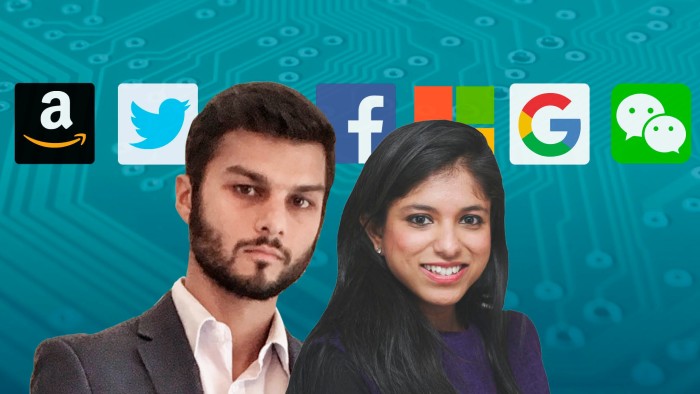

Madhumita Murgia, the FT’s European technology correspondent, and Kiran Stacey, FT Washington correspondent, answered your questions about AI and ethics throughout the day (BST) on Thursday May 13.

Here are the highlights:

FT commenter jat76: Have we reached the point where we need well-constituted, philosophical oversight in each country, appointed independently of governments and industry with legally enforced guarantees of press and TV coverage?

Madhumita Murgia: That’s a bold idea! I think creating groups of people who can approach this from a first principles, philosophical point of view is a good idea.

We did something like this in Britain in the late 1980s, where philosopher Mary Warnock led an ethics committee to investigate the implications of in vitro fertilisation (British scientists invented the technique). After the committee looked into it, there was a national consensus that IVF would be a net-positive advance for society, and the committee’s report led to the formation of the HFEA, an independent body that still exists today to regulate IVF treatment and human embryo research.

FT commenter Balthier: Amazon recently signed surveillance agreements with several US. Police Departments. While, at the same time, hiring US police officers to confront its worker. Have you any concerns about that?

Kiran Stacey: My colleague Dave Lee wrote an interesting piece on this earlier this year showing the sheer scale of Amazon’s partnership with police departments across the US:.

A lot of these issues are not particularly new — the prevalence of CCTV cameras in major cities has long been a worry for civil rights campaigners. The difference for me with this case is these cameras are not being controlled by a public body but by a large private company.

Last year Amazon fired four of its employees for snooping on customers. If there are a lot more cases like that, I would expect a massive consumer-led backlash.

FT commenter Charlie Pownall/AiAAIC: To what extent should the transparency and openness of AI, algorithmic and automation systems be legally mandated? Should it simply cover how a system works, its risks and impacts, or should access also be mandated to data, code and the model and, if so, to whom and under what circumstances?

Madhumita Murgia: This is a really good, and really hard question. Some might argue in favour of radical openness — allowing regulators or even users to see inside the belly of your code — but those I have spoken to from businesses developing AI say that often regulators don’t have the expertise to know what they are looking for.

Neither do they want to open up the model to customers, because they believe that will be a competitive disadvantage, and customers wouldn’t benefit from looking at a bunch of code anyway.

FT commenter Paulus: I think there needs to be EU regulatory focus on cloud services, how are they being built and are they using their customers data to build and enhance their offerings?

Kiran Stacey: I certainly think that there is a potential problem here about so much sensitive data being handled by so few companies. Take the Pentagon’s massive Jedi contract for example, which went to Microsoft back in 2019. The WSJ reported this week that this was now under scrutiny again, and the suggestion is it could be broken up and given to several different vendors instead — in part to improve security.

FT commenter The Dubliner: Do you think will the interesting example of self-regulation by Facebook, the Oversight Board, (a) work and (b) be copied by other tech firms?

Kiran Stacey: I think the oversight board’s decision on Donald Trump was clever because it gave the company some cover to continue banning Trump but also criticised Facebook for the way in which it did so.

The question will be what happens in six months’ time — the deadline which the oversight board has given the company to make a final decision on the ex-president’s status. If the oversight board disagrees with that decision, it will be interesting to see if it becomes a big dispute between the two or if Facebook backs down.

FT commenter Kevy Zhanje: Are there any government boards/ commissions specifically set up to educate or conscientise the public on new technologies, as far as they affect the public’s privacy and civil liberties?

Madhumita Murgia: I think there could be more focus on educating minority groups that tend to be under-represented in machine learning data sets, who will probably be disproportionately affected by inaccurate decision-making, for example.

One great example of this is the Citizens’ Biometric Council set up last year by the Ada Lovelace Institute in the UK. They brought together 50 members of the public and programmed a series of workshops and debates so they could learn (from experts) about technologies such as facial recognition, voice recognition, digital fingerprinting etc. They were exposed to perspectives on technical development, regulation, ethics, and politics/policy in these areas, and finally published a report to answer the question: what is or isn’t OK when it comes to the use of biometric technologies?

Do you want to read more questions and answers on AI and ethics? The conversation happened in the comments below, so read on.

Comments