Hedge funds bet on beaten-down Russia and Ukraine assets

Simply sign up to the War in Ukraine myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Hedge funds are scooping up Russian and Ukrainian assets after sharp declines since last autumn, while institutional investors stay clear as they view the intensifying political risks as too hot to handle.

Many big investors have become increasingly nervous about the possibility of military conflict in eastern Europe, with Moscow warning of “the most unpredictable and grave consequences” if the west rejects its security demands.

The notion that such tensions could lead to a war — and to western sanctions against Russia — has made financial assets in the region too difficult to hold for some large traditional managers, already jittery after a choppy start to the year fuelled in part by the prospect of tighter US monetary policy.

“The narrative is alarming. And investors are not prepared to take a high-profile political risk,” said Joseph Mouawad, emerging market bond fund manager at Carmignac.

Some hedge funds, however, are diving into the market in search of bargains, arguing that while Russian president Vladimir Putin is unlikely to back down soon, he will not want to risk a significant conflict.

“We’re quite confident there will be no war,” said David Amaryan, founder of Balchug Capital, a global fund run out of Moscow.

“I’ve talked to a lot of senior people in the Russian state. People are just going about their business,” he said. “If there was going to be a war, people would be acting in a different way. Everybody is quite calm.”

Amaryan said he had been buying some stocks in big Russian companies such as energy group Gazprom and financial services company Sberbank, describing the move as a “no-brainer” given stock valuations, dividends and the high oil price.

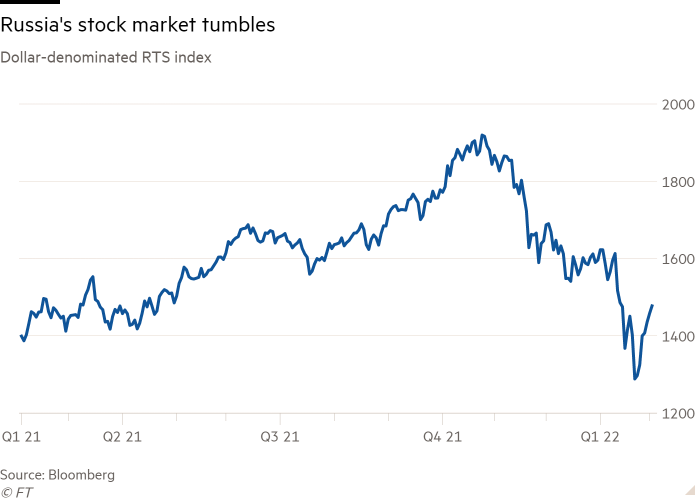

Russia’s dollar-denominated RTS index has fallen as much as 30 per cent since the end of October, although it has rallied over the past week and is now down 20 per cent over the period. Amaryan said he planned to “load up” if prices fall further.

“None of us are naive enough to think they’re going to shake hands and hug,” he said. “But any form of war is in no way beneficial to Russia . . . For me, the idea of Russia conquering Ukraine is absurd.”

Charles-Henry Monchau, chief investment officer at Geneva-based Bank Syz, noted that profitable Russian exporters and banks had been “hit massively” and this could create opportunities.

“This is exactly where you need to be,” said Barry Norris, chief investment officer at UK-based investment firm Argonaut Capital, who has positions in blue-chips such as Sberbank, Gazprom and Lukoil, although he has also been betting against some smaller, more highly valued stocks that he thinks could suffer in the short term.

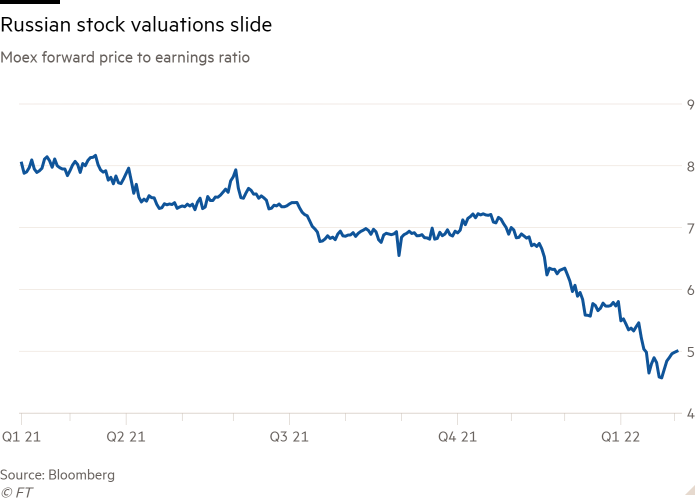

Overall, Russia’s Moex equity index is trading at about five times expected earnings over the next year, a steep discount compared with about 21 times for America’s S&P 500.

Norris said the Russian market’s heavy weighting towards big energy companies and relatively low valuations mean it “should be one of the best-performing equity markets in 2022”.

Some managers also see an opportunity in Ukraine’s sovereign bonds. A Ukrainian dollar bond maturing in 2032, for example, was trading on Wednesday with a yield of 9.6 per cent, compared with less than 2 per cent on a 10-year US government bond.

“We believe that if you look at it from the Russian perspective, escalation makes a lot of sense but not a war,” said Pavel Mamai, founding partner at London-based emerging markets hedge fund ProMeritum Investment Management. He has been buying the bonds in recent months and partially hedging his position by betting some Russian assets will fall.

“Ukraine’s [international bonds] are certainly pricing a tail risk of war . . . There’s been a lot of panic selling,” said Mamai, whose fund has made money in each of the past five years, according to numbers sent to investors.

Still, many institutional money managers remain wary of investing in Russian or Ukrainian assets given the intense uncertainty and rising tensions between Moscow and western nations.

Vincent Mortier, deputy chief investment officer at Amundi, which manages €1.8tn in assets, said it was “difficult to hedge” against the worst-case scenarios and that traditional tools to protect against risks of such an extreme, yet highly unpredictable, event do not work well in this situation.

The crisis “is typically a black swan/tail-risk event that is difficult to prepare for as the probability it occurs is still pretty small”, he added. “But if it occurs then there can be some Armageddon-type consequences.”

John McAuley, co-head of North American debt capital markets at Citigroup, cautioned, meanwhile, that the crisis marked the return of “old fashioned overnight risk in geopolitics” for investors.

Dan Brocklebank, director at Orbis Investments UK, which manages £28bn in assets, said that while the situation could present opportunities, there were good reasons to be cautious.

“While we believe that you have to be willing to act in a contrarian manner to be successful in investing, you can’t be contrarian for the sake of it — buying shares in Lehman Brothers, Theranos or Enron on the way down would have been contrarian, but not very smart,” he said.

Additional reporting by George Steer and Katie Martin in London and Joe Rennison in New York

FT Asset Management newsletter

Our weekly inside story on the movers and shakers behind a multitrillion-dollar industry. Sign up here

Comments