Meet the teens who want to work in finance

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

What do bankers actually do? Could our personal data become a new form of currency? And will high street bank branches be no more than a memory in 20 years’ time?

These questions were among those pondered by more than 220 student hopefuls who entered the FT’s competition to find the best young personal finance writers in Britain.

Organised in partnership with the London Institute of Banking & Finance (LIBF), its own research shows that young people worry about money and feel they don’t get enough financial education in school.

“With this competition we hope to show them that, with just a little effort, they can turn a ‘scary’ subject into something that’s relevant, interesting, and one they want to find out more about,” says Catherine Winter, managing director of financial capability at the LIBF. “Managing money well is a critical life skill.”

Our three winners, whose edited entries appear below, must now decide how to invest their £150 prize money.

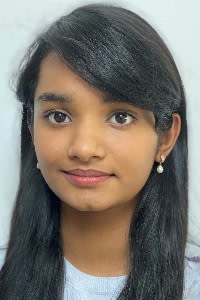

Adya Manoj: A career in finance will help you save more than just money

Adya Manoj, the 17-year-old winner of the 16-17 age category, is studying for her A-levels at the Tiffin Girls’ School, Kingston upon Thames, and hopes to read economics at university. “My economics teacher at school told me about the FT competition,” she says. Having written about exploring a career in finance, winning the competition has created a new dilemma: “Maybe I should also consider journalism?”

“It is not about having lots of money, it’s about knowing how to manage it.”

My best friend burns her tongue on her £4 Venti Gingerbread Latte from Starbucks as she divulges this golden nugget of information to me. I remember reading the same quote on Pinterest a month ago.

The truth is, neither of us really know how we will control our finances in the future, or how they will control us.

Hundreds of thousands of people in the UK are directly employed in financial services; bankers, accountants, financial advisers and more. People who not only control their own finances, but have great influence over yours too.

Is that enough of a reason to consider a career in banking and finance though? What else does this cryptic industry have to offer?

Most people are aware that wages in the financial sector are high — unsurprising in a sector that revolves around money. Bankers are often villainised; Mark Twain famously stated that a banker is someone who lends you his umbrella when the sun is shining, but wants it back the minute it begins to rain.

The Wolf of Wall Street stereotype endures, but the lives of most people working in finance are far less glamorous and self-involved. They are not solely motivated by the personal benefits they receive, but the impact they can have on their community and society.

Some spend their lives advising others how best to manage their hard-earned cash, be that buying their dream home, helping parents save for their children’s university education, or helping pensioners fund their retirement.

The positive impact you could have in this sector stretches globally. The World Bank has two main aims: to end extreme poverty and promote shared prosperity.

Since I wrote this article, the World Bank says the Covid-19 crisis “will have a disproportionate impact on the poor, through job loss, loss of remittances, rising prices, and disruptions in services such as education and healthcare”.

For the first time since 1998, it expects poverty rates will go up as the global economy falls into recession.

However, the global response to Covid-19 is proving just how critical financial services can be in times of crisis. Online and contactless payment systems have helped facilitate social distancing; interest rate cuts and payment holidays are enabling businesses and households to withstand the economic shocks.

Around the world, investors and financial analysts must decide how best to allocate capital considering the social, economic and political implications as well as the opportunity cost. It is a tremendous responsibility, but making better financial choices can change lives.

The gingerbread latte has gone cold, but the reality of this poor investment has only just begun to set in.

So I will consider a career in banking and finance. Maybe you should too.

Lindell Brown: Personal data, the new gold mine for corporations?

Lindell Brown, the winner of the 18 and over category, is studying business, finance and economics at East Norfolk Sixth Form College. He reads the Financial Times every day online via FT Schools and has recently started trading in his spare time.

He recommends that other young wannabe investors should read “Market Wizards” by Jack D Schwager. “It’s a really old book from the 1990s, but he interviews rich and famous traders and asks loads of really good questions,” he says. “If I could work as a technical investment analyst in future, that would be my dream job.”

In 1848, James W. Marshall discovered gold at Sutter’s Mill, California. As the news got out, over 300,000 prospectors flocked to the US state. The economy was reinvigorated; a posse of hopefuls had come mining for the most valuable asset on Earth.

More than 170 years later, they’re still mining for the biggest prize in California — except this time, it’s our personal data.

Data has become a hot topic with the rise of social media and it’s no secret that the most powerful corporations on the planet want as much of it as they can get. So why do we give it to them?

Maybe it’s because as millennials, we have no valuable assets. We don’t know how to save responsibly or spend reasonably, so we rely on our personal data to act as our place holder.

It wouldn’t take you more than five minutes to find my name, email and my favourite food online.

We might be a bit more careful with personal data such as our date of birth, birth town, phone number and what we’re spending our money on. Yet we will share this with our friends, family and the 2,000 contacts that we have on Facebook.

The problem is, we have handed the big businesses all of our information for nothing and our “friends” don’t really care.

For example, fewer than 5 per cent of my “friends” on Facebook and Instagram wished me a happy birthday when I turned 18 (you could argue that I have very uncaring friends). However, I was inundated with emails from banks, clothing websites, restaurants — you name it, they were all lining up to give me an amazing deal to spend my birthday money on.

Big businesses will never forget your birthday. Why? Because they want nothing more than to make a profit out of your most “valuable asset”.

They will take your data and (if you let them) share it all around for everyone to benefit from. Like gold, your data can be mined to make a profit.

Will Lawson: How new technology can change the future of banking

Will Lawson, a 14-year-old student at St Olave’s School in Orpington, was the winner of the under-16s category. Already a keen reader of the FT Weekend newspaper, Will says he would love to pursue a career in finance or politics in the future. “The last article I read was about the oil price turning negative,” he says. “Why would you want to pay people to take it away? It’s worrying, but fascinating.”

In 1994, when Bill Gates said: “Banking is necessary, banks are not,” it would have seemed rather far-fetched. Now, with fintech revolutionising the world of retail banking, it doesn’t seem that outlandish at all.

Over the next 20 years, the banking system we have grown to recognise could be gone forever.

App-based banks such as Monzo question what it means to be a bank. Online-only banks are able to avoid the huge costs of running high street branches, allowing them to invest in better technology and offer more competitive interest rates.

Others are able to use technology to cut costs of providing a service. Payments technology is expanding and cryptocurrencies offer a future alternative to using banks to store and move money.

Mobile and internet banking is more popular than ever, and continues to become safer and simpler for customers. Although the changes will be difficult for some age groups, online banking is far more convenient and also more accessible for young people.

The steady reduction of high street branches shows banks have every intention of withdrawing from many high streets around the UK. Whilst I wouldn’t go as far as to say “banks are not necessary”, they are now in a far more competitive market. As that market moves further online, high street branches may soon be a far rarer sight.

FT Schools

Students aged 16-19, their teachers and schools around the world can get free access to the FT to help with their studies, exams and preparation for further education or employment, as well as get insights into finance and careers. Check to see if your school is registered here: FT.com/schoolsarefree

Comments