Will China have to loosen policy?

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

This article is an on-site version of our Unhedged newsletter. Sign up here to get the newsletter sent straight to your inbox every weekday

Good morning. We have stimulus on the brain today. Will China be forced to resort to it, and did it work during the scary, early days of Covid? Send us your thoughts: robert.armstrong@ft.com and ethan.wu@ft.com.

Will Evergrande force China into a policy shift?

The latest news on Evergrande suggests that the property developer is very close to default, and the shares of the super-indebted group say pretty clearly that it is going to happen. The shares fell 20 per cent on Monday, a move barely visible on the long-term chart:

The Chinese authorities seem to be trying to do with Evergrande what they did successfully (to date) with the over-extended insurer Anbang: some sort of orderly, break-upy, liquidationy thingy which will not require a general bailout of the sector, or fiscal and monetary juicing of the economy.

This will involve state-owned entities taking Evergrande’s assets and liabilities at prices that will not require big losses to be recognised. The government’s goal is “to reach a balance between short-term stability and long-term reforms”, as Chaoping Zhu, of JPMorgan Asset Management, put it in the Financial Times today. Which is, if you think about it, what we’re all trying for in life, isn’t it?

But this balance requires discipline, and there are a few signs that China might engage in a general easing of financial conditions, of the sort that encourages rather than discourages risk-taking, but which eases the short-term pain — and supports markets.

The first clue that official discipline might not be ironclad is, of course, the People’s Bank of China cutting the required reserves ratio (RRR) by 50 basis points on Monday, the second cut this year. This will release credit into the economy.

Another, subtler form of support for the economy is purchases of land rights by local government financing vehicles. LGFVs (state-owned enterprises that fund public projects) are filling the void in local budgets left by cash-strapped developers, who have pared back land purchases. As reported in Caixin Global last week:

LGFVs have bought more land use rights nationwide starting the third quarter when the cash crunch at some private property developers worsened, and in some places these vehicles became the major bidders. From July to November 15, LGFVs bought 13.38% of land parcels by value across the country, up 4.38 percentage points from the January-to-June period, according to calculations by brokerage Zhongtai Securities.

Here is Michael Pettis of Peking University discussing these moves on Twitter:

These LGFVs are controlled by local governments and borrow under their guarantees, so that this effectively means that local governments are borrowing from the banks and treating the proceeds as if they were revenues. I am surprised this is allowed, but I guess local governments have little choice if they can’t otherwise sell enough land to meet revenue needs.

But this represents a doubling down on the property sector. Why? Because if the property market revives, and prices continue to rise, the LGFVs can then sell the land on and make a profit. But if the property sector doesn’t revive, the LGFVs will be sitting on losses on which local governments will have to make good.

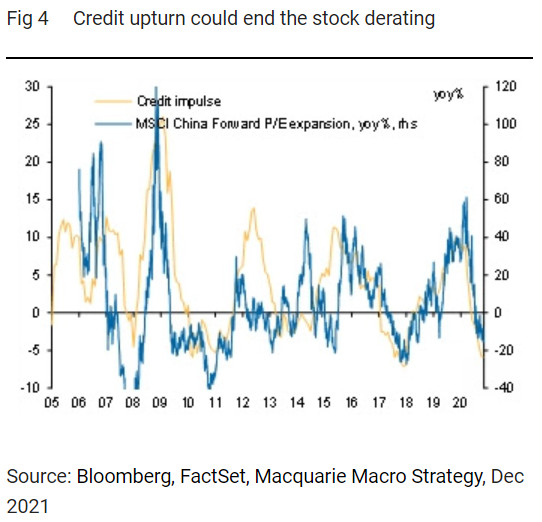

Are moves like these signs of more accommodative policy to come? Larry Hu and Xinyu Ji, China economists at Macquarie, think they are. The RRR cut and the “dovish” tone at Sunday’s Politburo meeting suggest the “policy priority is shifting from regulatory tightening to supporting economic growth” and “monetary and fiscal policies would turn from tightening to loosening in the coming quarters”, though gradually.

They suggest that the “credit impulse” (new credit’s contribution to gross domestic product growth) has bottomed and will turn up, and fiscal deficits, which have been falling for a year, are ready to increase again. The result? Stock market valuations should rebound:

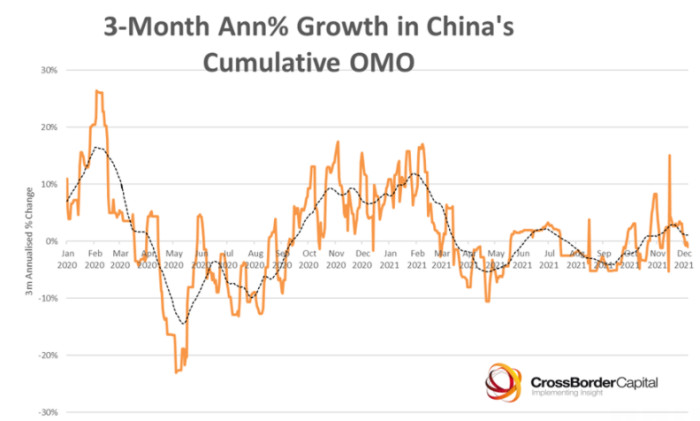

Good times. But not everyone agrees with this picture. Michael Howell of CrossBorder Capital, who follows China credit and liquidity closely, sees little evidence that policy will loosen. He notes that as of the first week of December, PBoC open-market operations (buying or selling bonds from banks, basically) are adding no new liquidity to the economy:

Obviously, offering an independent prediction about Chinese policy is way above Unhedged’s pay grade. But seeing how disciplined the Chinese authorities will be in the face of the Evergrande test will be one of the most interesting dramas of the coming months.

Stimmys and lockdowns

The US’s response to the frightful early days of Covid was twofold: strenuous lockdowns and plentiful fiscal stimulus. Lockdowns were meant to “crush the curve” and prevent mass hospitalisations, while fiscal support kept those stuck at home afloat.

Whether this was a good policy mix will be studied for decades. But early evidence suggests that pairing lockdowns with fiscal largesse gets messy quickly.

A paper from four economists (Alan Auerbach and Yuriy Gorodnichenko of University of California, Berkeley, Daniel Murphy of University of Virginia, and Peter McCrory of JPMorgan) suggests that lockdowns diminish the efficacy of stimulus. From the paper:

Our evidence implies that fiscal stimulus is indeed more effective in recessions, but not if there are restrictions on spending or other forms of economic activity. Lockdowns effectively restrict the ability of the economy to absorb slack, and there are no detectable consumption responses that would contribute to stronger general equilibrium effects of government spending.

If you’re stuck at home and the shops are closed, it’s hard to go spend that stimulus cheque. You might buy a new dress online, but you’ll probably just save the money. Studying April through to June 2020, the authors found no link between government spending and higher local consumption (ie, buying from your town bookstore rather than Amazon), even in areas without lockdowns.

When we spoke with Professor Auerbach, he recalled just how unprecedented the situation was. So while the lockdown/stimulus cheque combination might have been a bit self-defeating, the crucial point is that catastrophic economic damage was avoided.

The lesson — familiar but worth repeating — is that we have never been here before. We didn’t know what was going to work during the crisis. We should not be too sure about how the recovery is going to play out, either, in markets or anywhere else. (Ethan Wu)

One good read

Some financial advice from Courtney Love.

Comments