Erling Kagge: ‘It’s not rational to be an art collector, it’s an obsession’

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

When the Norwegian polar explorer, publisher, lawyer, writer and art collector Erling Kagge was 13, he saw a Richard Long stone circle in the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art in Copenhagen.

“They were the same rocks as we had next door to my home in Oslo,” he recounts. “At first I just laughed . . . but then I wanted to grasp what that piece was about . . . I realised you can’t walk around being negative and doubting everything. Like contemporary art or life in general — you have to believe in it.” And that early encounter with land art certainly resonated with him: “I have always been into nature, even as a child,” he says.

We are talking over Skype. He is in a book-lined room in his Oslo home, the 1932 Villa Dammann, designed by Arne Korsmo and Sverre Aasland, a landmark of Norwegian Functionalism. Kagge is tanned and athletic-looking — hardly surprising, as he has met the “three poles” challenge, having reached the North and South Poles unsupported in 1990 and 1992-93, and climbed Everest in 1994. As we talk, he runs his fingers through his slightly unkempt hair and gestures with his hands to make points; I think he might be happier talking to me while walking, as he has done in other interviews.

Kagge, 57, has written a book about walking, titled One Step at a Time, and another, Silence: In the Age of Noise, inspired by his 50-day solo trek in Antarctica with a broken radio. He has also written A Poor Collector’s Guide to Buying Great Art, based on his experience of building a 800-strong collection of contemporary art. A selection of his holdings is going on show at the Fondation Vincent van Gogh in Arles (from October 3) in an exhibition called My Cartography and curated by Bice Curiger. Other parts of his collection are on view at the Museion in Bolzano, Italy (until February 14), where Kagge has also been guest curator this year.

Some interviews have emphasised the link between Kagge’s exploring and his art collecting. I ask if there really is a link. “Yes, absolutely,” he responds. “This is true in the sense that collecting is about wonder, about curiosity, about making life more difficult than it has to be.” In the past he has noted that his comfortable, cultivated background (his father is a jazz critic and his mother worked for a publisher) meant, for him, that he had to seek out difficulty, unlike, say, someone born in a third-world country: “To make life meaningful, you have to make it more difficult than it has to be.”

“Contemporary art is very difficult to understand, but I think walking long distances and collecting art are both about fulfilling the potentials you have in life,” he says. I ask what those potentials are. “It is a very egocentric thing to do,” he answers, “just like walking to the Poles. Doing it for yourself — egocentric, but not egoistic. I don’t buy art because I want to share it, I buy it because I love it. I want it to be part of my life, I want to be challenged by it. It’s great that people want to see my collection, but I didn’t buy it because of that.”

His first acquisition was a lithograph inspired by Munch, swapped for two bottles of wine at a party, when he was 21. “At that time I didn’t have much money, but later, when I started to earn well [he founded Kagge Forlag, one of Norway’s leading publishers, in 1996], I started spending all my money on art.”

His collection comprises Norwegian artists such as Torbjørn Rødland, Vibeke Tandberg, Ann Cathrin November Høibo, Hanneline Røgeberg, Lars Elling, Matias Faldbakken, Pushwagner, Gardar Eide Einarsson, all of whom are in the Bolzano exhibition. But he also collects many international names, among them Olafur Eliasson, Klara Lidén, Diane Arbus, Tauba Auerbach, Trisha Donnelly, Raymond Pettibon, Wolfgang Tillmans and Franz West. Famously, he bought a series of Franz West car bonnet ornaments — and got the Rolls-Royce that went with them, designated as a “plinth”.

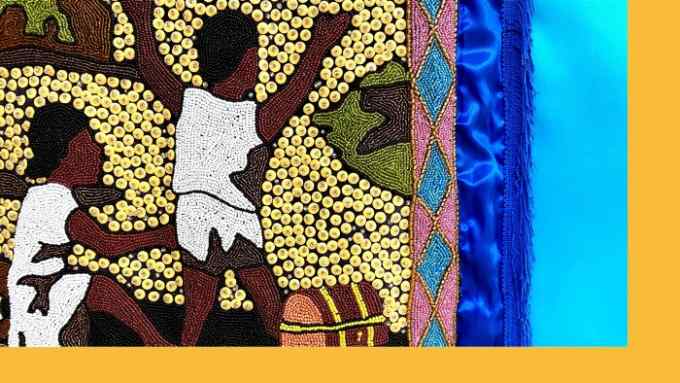

His collection is difficult to categorise, ranging from photography, such as Arbus’s “Department Store Santa” (1964) to an Urs Fischer tongue poking out of a wall (“Noisette”, 2009), but a thread of interest in nature and people runs through it.

With such a large collection, I ask how much he can actually keep at home. “I have art under my bed, everywhere,” he answers. “I admit it’s not rational to be an art collector . . . it is an obsession, and sometimes I buy something, then regret it because it’s so much money.”

He has three daughters (aged 18, 21 and 24) who are “in and out of the house”. They want to go to college, he says, which sometimes reins in his spending. I ask if they are interested in art. “I took them to galleries and museums when they were young and at one point they hated art, but now they love it. We go to Art Basel and exhibitions together, I show them what I am buying or thinking of buying. It is a great privilege to have that in common with them.”

“I don’t like selling,” he says, “but I did sell a Nurse painting by Richard Prince. It had gone up 100 times in value, and I ended up being fonder of the money than of the work!” The painting, bought for $50,000, sold for $5m; with the money, he took his daughters on safari and spent the rest on art.

His book, as the title suggests, is aimed at the “poor collector”, but, I say, art is expensive for most people. He disagrees: “I chose the title because it’s catchy,” he replies, “but I do think that with a fairly good income you can buy art. I just bought a beautiful edition by the American artist Nicole Eisenman for about €400-€500. If you go the Artists’ Space in New York, they have portfolios for about $1,500. You can buy editions from the Serpentine . . . you can get work from some of the best artists in the world for not too much money. The framing costs almost as much!”

So, I ask, what is the future of such a large collection? “At the moment, I don’t spend my time wondering about what I will do with it, but I think that when the time comes, I will give a lot away.” He certainly doesn’t envisage a private museum, preferring, to devote his money to the art itself.

We are coming to the end of our talk, but he makes a final plea about the environment: “One of the biggest problems we have today is separating ourselves from nature. We are not listening to nature any more. We can’t stay sitting all day in a chair.” And, with that, he announces that he is soon off to Bolzano where, as he tells me later by email, “I just did a hike in the hills.”

‘My Cartography’, October 3-March 28, fondation-vincentvangogh-arles.org

‘Walking. Movements North of Bolzano’, to February 14, museion.it

Comments