Chinese dream readjusted: why uncertainty dims aspirations

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

This article was originally published as part of the ‘China’s Slowing Pains’ series on 15 May 2019.

One recent evening at sunset, Tao Jiali went to the rooftop of the tech company where she works, eight storeys above the highways of Hangzhou. A low guardrail separates the roof from the hazy skyline. “That’s where employees go to take selfies before they’re laid off,” she says.

In recent months her company, NetEase, has suffered from the same wave of redundancies that has hit the rest of China’s internet sector as the industry slows. Two months ago, Ms Tao was told by her supervisor that she would lose her job, too — but that decision was suddenly reversed. She had just started breastfeeding her newborn daughter, a period when employees enjoy special protections under Chinese labour law.

That time is up in three months, she says. After that her future feels uncertain. “I don’t know how to plan. I might as well take the photos now.”

Ms Tao joined NetEase two years ago, her fourth job after moving from company to company for ever-higher salaries. Such jumping about has been normal in Chinese tech: according to data from LinkedIn, the average tenure is 1.5 years. She thinks that fluidity in the job market is over.

At the time she was hired, companies were expanding rapidly. Interviews were pro forma, she says. Now she faces the prospect of looking for work in a downturn. She also worries that prospective employers will put her in the category of undesirable potential employees: married women who might be about to get pregnant.

“Overall, we’re very fortunate,” she says of herself and her husband, also a high-earning tech employee. “It’s just that there are a lot of fragments of life we have to worry about.”

China’s Slowing Pains

After three decades of strong growth, the world’s second-largest economy has been slowing. In this series the Financial Times examines the implications for business and society.

Part one

The struggles of entrepreneurs

Part two

Data beyond the national GDP

Part three

Chinese dream readjusted for the middle class

Part four

FT reader responses

Explore more from the series here.

To many, it may seem somewhat strange that Ms Tao has any worries at all. She and her husband have a joint annual income of Rmb500,000 ($72,700), putting them very easily in the top 10 per cent of earners in China.

Her husband has a house to his name, and there are an additional three houses owned by their parents who all live near them and can help with childcare, as is traditional for Chinese grandparents. Being from Hangzhou, they have access to a local hukou or household registration that gives them access to schooling and social security benefits.

But Ms Tao still feels far from secure. She considers her household barely middle class. She and her husband save some Rmb10,000-Rmb20,000 per month, but her aim of buying a house feels distant. She wonders whether she’ll be lucky enough to get her daughter, Juanjuan, into a primary school that stands a chance of placing her in a good lower secondary school, which means better odds of a good upper secondary and university education.

In short, she suffers the typical anxieties of a young Chinese professional family. “When I was pregnant with Juanjuan, I thought about enrolling her in a ballet class when she was older,” she says. “I thought I was being so advanced. Then I found out all the other mothers had already thought about it.”

Ms Tao’s situation is partly the consequence of structural shifts in China’s economy and society that have been forming over the past three decades, since privatisation started in earnest. The insecurity of the middle classes is described by Chinese commentators as arising from growing inequality coupled with falling social mobility — known as “class solidification”.

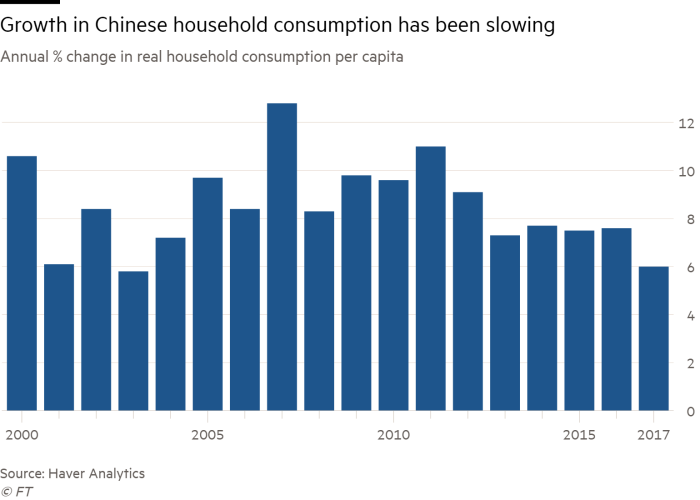

But Ms Tao is also starting to bear the costs of the economic slowdown that has been brewing for the past nine years. While annual GDP growth of more than 6 per cent is higher than nearly all western countries, it is much lower than many Chinese businesses and households have grown used to.

At the heart of the problem is China’s financial system. The government drew on banks to provide heavy lending during the boom years, but is now trying to cut back. The authorities are dealing with the consequences of abundant loans that ended up fuelling unprofitable ventures, dodgy consumer-lending schemes and property prices.

As a result many tech companies are still growing, but laying off workers. Investments still garner returns, but millions of individuals, including Ms Tao, lost savings in the bursting of the peer-to-peer lending bubble. House prices in big cities have gone from rapid growth to stability, but only because of government restrictions on house purchases that have irritated owners and would-be buyers.

Mismatched expectations are at the heart of Ms Tao’s anxieties. “First generation middle classes generally have stronger material desires, they want to chase a higher goal and have more motivation,” said Li Chunling, researcher at the Institute of Sociology of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences.

But, Ms Li added: “It won’t be like in the past, when living standards improved every year, they may be stagnant or even drop. But the middle classes haven’t changed their mindset yet.”

Eating dinner with her parents, Ms Tao spoons imported fruit purée into Juanjuan’s mouth, which costs Rmb30 per sachet. “I don’t know if it’s safe. But it’s more expensive so it’s more safe,” Ms Tao said. Her fears stem from China’s baby-milk food safety scandal more than 10 years ago, when thousands of babies were hospitalised and some died after drinking contaminated formula.

Ms Tao’s mother, who was born in 1957, smiles: “Things were much simpler when I gave birth to Jiali. We didn’t think about any of these things. I fed her rice porridge long before I should have, but nobody knew better back then.”

Ms Tao’s parents, who were born into a China of almost uniform poverty and witnessed unimaginable economic growth, belong to an optimistic generation. Ms Tao’s has lived through a boom followed by a slowdown in their adulthood. They have formed expectations, especially for their children, of a quality of life that no longer feels guaranteed. “It’s easy to go from frugality to luxury, but difficult to go from luxury to frugality,” she said.

The “iron rice bowl” welfare state that fed Ms Tao’s parents has also been taken off the table. Despite being socialist in name, China provides basic employment and medical insurance. The rule of law itself is haphazard, adding an edge of uncertainty to everyday challenges.

“My husband is rarely angry, but I once saw him yell at an old man from road rage,” Ms Tao said. “I scolded him for it. What if the old man had a heart attack and needed to be hospitalised? We’d have to pay for his fees.”

Two words that crop up repeatedly when Ms Tao talks about her life are “competition” and “lottery”. She and her husband want to buy a house near their wished-for secondary school, Hangzhou Jianlan, but have to save up a downpayment of 60 per cent — a measure imposed by many local governments across China to stem soaring property prices.

“The rapid growth of the economy created many opportunities, and these opportunities widened differences among people . . .[Now] you need fierce competition to get these opportunities,” Ms Li said.

Competitive pressure to get into top schools is so great that the best schools interview parents and ask for CVs from 11-year-olds. Even oversubscribed primary schools sometimes require applications. The 14-page CV of a five-year-old in Shanghai went viral recently. He cited achievements such as “reading over 500 English books a year”.

To Ms Tao, it feels like the whole of Hangzhou is chasing the same resources she is. This sentiment is backed up by research. “The allocation of educational resources is extremely uneven,” said Guo Bin, professor of management at Zhejiang University. “There are huge differences even within big cities.”

We walk past Ms Tao’s dream primary school for her daughter. Ms Tao admits that she does not dare waste her one application space on it. Many other parents will be eyeing it up too, especially since President Xi Jinping has visited several times.

Instead, she plans to enrol Juanjuan in English classes from the age of two or three, as well as ballet and other activities that can add to her CV. “So much pressure,” she jokes, stroking Juanjuan’s feathery head, “her hair is already falling out”.

On Saturday, Ms Tao’s husband is still at work. Ms Tao laughs, calling it “more than 996” (9am to 9pm, six days a week). The number 996 recently became a buzzword after a movement of tech workers started a campaign against long working hours. Jack Ma, Alibaba’s boss, opposed it, saying that long hours were a “blessing” and a test of strength.

An ethic of hard work has long been part of China’s image, both at home and abroad. But Mr Ma’s words seem out of date now. In the past two years, stories have gone viral on social media of young professionals getting sick or even dying because of working overtime.

But plenty of the country’s brightest young people put up with the 996 regime after acclimatising to long hours of study during the notoriously competitive gaokao university entrance exams. Many also believe an opportunity may be closing.

“Everyone feels that class solidification is coming, but it has not completely happened. Therefore, everyone thinks that they still have the opportunity to get out of their own class,” said Wang Wen, executive dean of the Chongyang Institute for Financial Studies at Renmin University.

In developed countries, he argues, families have a lower expectation of class mobility — whereas in China, people still feel there is something to play for. That, in turn, leads to anxiety.

With her husband working at the weekend, Ms Tao and her parents take Juanjuan to Hangzhou’s zoo, by the famous West Lake that formed the core of the old city. This is the area that Marco Polo visited in the late 13th century, when he declared Hangzhou the finest city in the world.

“I’m nostalgic about the city before the tech giants came,” said Ms Tao, who recognises the irony in saying so given her high-flying high-tech career. “The city has grown and so have our ambitions.”

Looking back, Ms Tao and her mother say that they only noticed competitive pressure in their own lives when Ms Tao entered high school, in the early 2000s. Academics echo this point, saying that the increasing emphasis on competition coincided with the marketisation of the Chinese economy after it acceded to the World Trade Organization in 2001.

“The rapid changes in society and the possibilities brought about by these changes mean everyone has high expectations for change. When there is a huge gap between high expectations and relatively low possibilities, there comes social anxiety,” said Mr Wang.

Ms Tao’s parents were keen for her to stay near home for university, so she has never lived elsewhere. However, she recently mused over emigrating to the US while on a holiday. “I said to my husband, [how] about we buy a house, and move here?” she said. She dropped the idea quickly, after thinking she would not find work easily.

Her husband, on the other hand, had different reasons for staying put: “Look at China’s technology sector. China will overtake the US, so it’s best for Juanjuan to grow up here,” he said.

Photographs by Lao Ma

Additional reporting by Archie Zhang

Do you or your family live in China? What changes have you experienced since the slowdown started? We would like to hear your thoughts and personal stories in the comments below.

Comments